“The Greatest Yiddish Writer You Never Heard Of.” —Forward

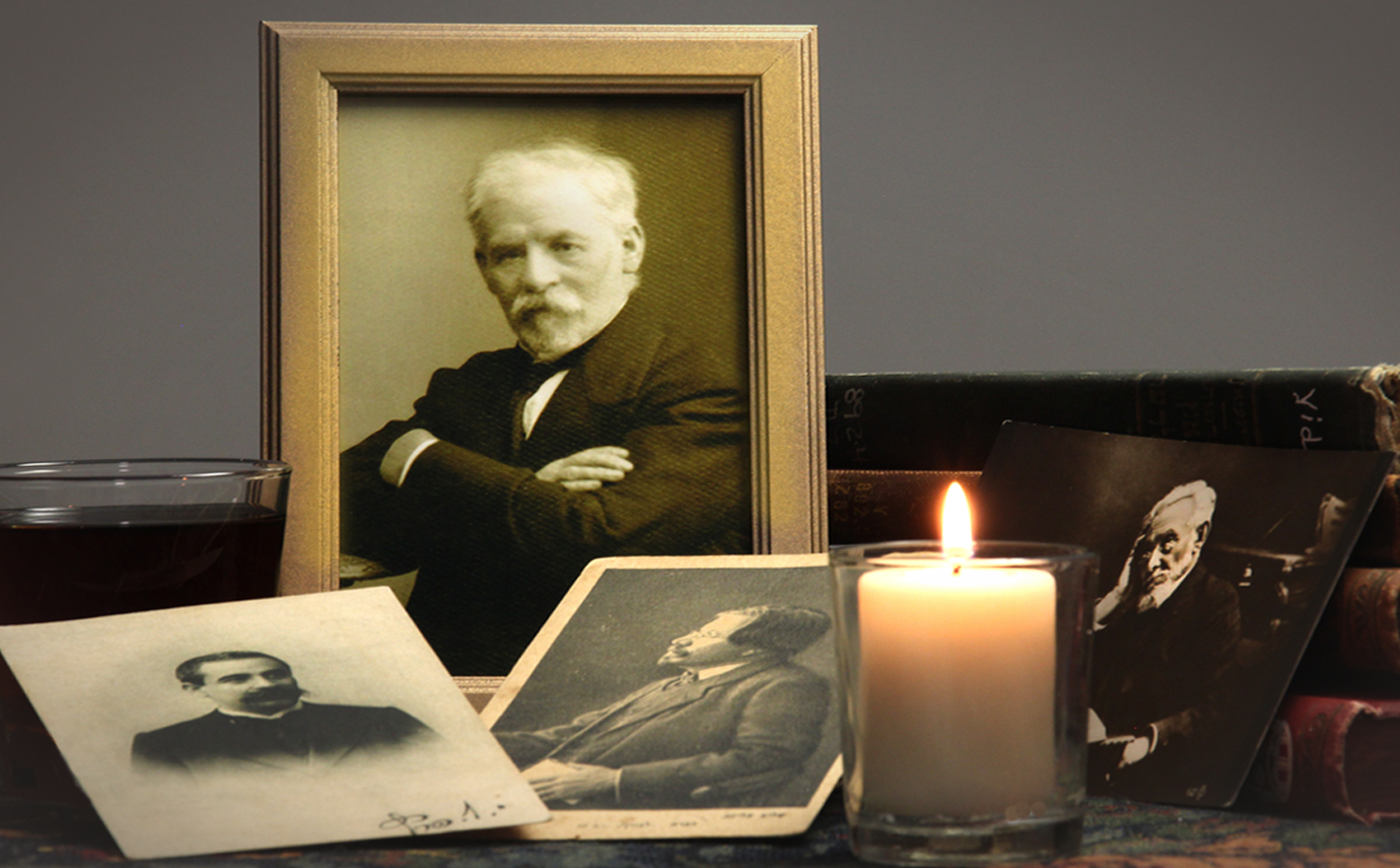

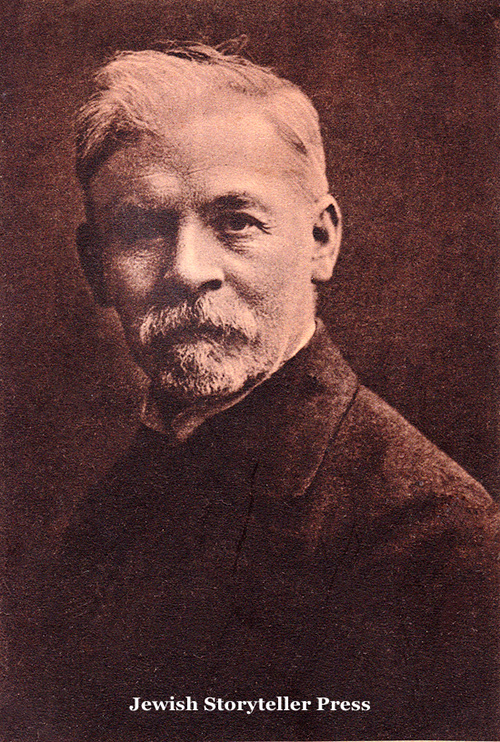

Jacob Dinezon (1851-1919) was one of the most famous and successful Yiddish writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Friend and advisor to many of the most important Jewish writers of his day, Dinezon played a central role in Warsaw’s Yiddish literary circle until his death in 1919.

A best-selling novelist in his own right, Jacob Dinezon, like the British author Charles Dickens, championed the rights of the oppressed and poor, especially children. A staunch defender of Yiddish as a literary language, he used his pen to expose the conflicts and challenges Jews faced in rural and urban communities, and his stories reveal a deep commitment to educating and uplifting the Jewish people.

“Two authentic folk writers were ours: Dinezon and Sholem Aleichem. It doesn’t occur to anyone to put these two writers on the same level. Yet it is so: in their main artistic accomplishments they are paradoxically alike. Dinezon is the tearful one and Sholem Aleichem is the clown. . . . You will cry as naturally reading Dinezon as you will naturally burst into laughter with Sholem Aleichem.” —Alter Kacyzne (trans. Miri Koral)

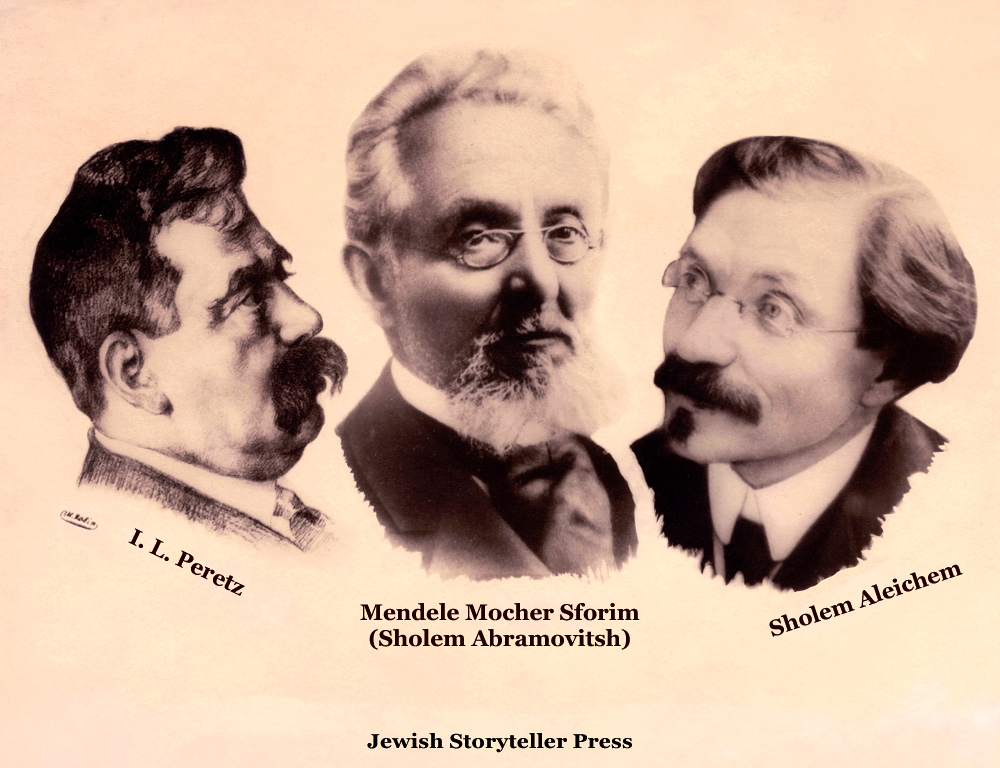

Yet, Jacob Dinezon’s role in modern Yiddish literature was sadly overlooked following his death in 1919. The horrors of the Holocaust and the decline of Yiddish in the years that followed have diminished our understanding of Jacob Dinezon’s true place among the Yiddish literati of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Unlike his friends and writing colleagues, Sholem Abramovitsh (Mendele Mocher Sforim), I. L. Peretz, and Sholem Aleichem, who are now considered “the classic writers” of modern Yiddish literature and whose works have been translated into English in several volumes, Jacob Dinezon’s stories and novels remained untranslated and neglected. And with the passage of time, Dinezon’s important contributions to Yiddish literature were all but forgotten.

“It seems that in every place and in all times the Jewish heart is filled with troubles and tears. One just needs to know the right word or the touching melody, and the thick ice that forms around the Jewish heart by cold life breaks open and tears pour out.” —Jacob Dinezon, Memories and Scenes: Shtetl, Childhood, Writers (trans. Tina Lunson)

Until now.

Over the past two decades, the Jacob Dinezon Project has commissioned English translations of Dinezon’s Yiddish short stories, novellas, novels, and a wealth of research materials in an effort to bring Dinezon’s remarkable accomplishments to 21st-century readers.

Now, books, e-books, and even an audiobook are available for reading, studying, and better understanding Jewish life at the turn of the 20th century, as seen through the eyes of one of Yiddish literature’s most sensitive, compassionate, and respected authors.

“Dinezon’s writing is poignant and haunting; his characters are bright, intense, and unforgettable . . . . Jacob Dinezon is truly a giant in Yiddish literature.” —New York Journal of Books

This website serves as a clearinghouse for the many memoirs, letters, biographical profiles, articles, essays, newspaper reports, and obituaries that have been translated from Yiddish into English. It provides a treasure trove of insights into Dinezon’s world and his role in the development of Eastern European Jewish literature, culture, and community activism.

It is our belief that if Dinezon’s friends, Mendele Mocher Sforim, I. L. Peretz, and Sholem Aleichem are (as scholars suggest) the grandfather, father, and grandson of modern Yiddish literature, then Jacob Dinezon is surely the beloved uncle, producing novels and stories filled with compassion and love for the Jewish people.

“There is somewhere in a city called Warsaw, on Dzielna Street, a slight, slender, pale little man with small but clean little hands, with a whitish little beard—it once was reddish—and with kindly, always-smiling eyes even when moist with tears. Always clean and neatly dressed, his little boots shining, smoking his own wee cigarettes with his little curling fingers, drinking his own tea brewed from his own little teapot, and always sitting on the same chair at the table, where he keeps hidden an endless array of secrets, troubles, and hurts from all the strangers for whom he has given away a piece of his uncommonly big heart. And this good uncle is named Uncle Dinezon.” —Sholem Aleichem (trans. Miri Koral)