By Alter Kacyzne

From Literarishe bleter (Literary Pages)

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Warsaw, October 3, 1924, No. 22, Pages 2–3

Translated from the Yiddish by

Miri Koral

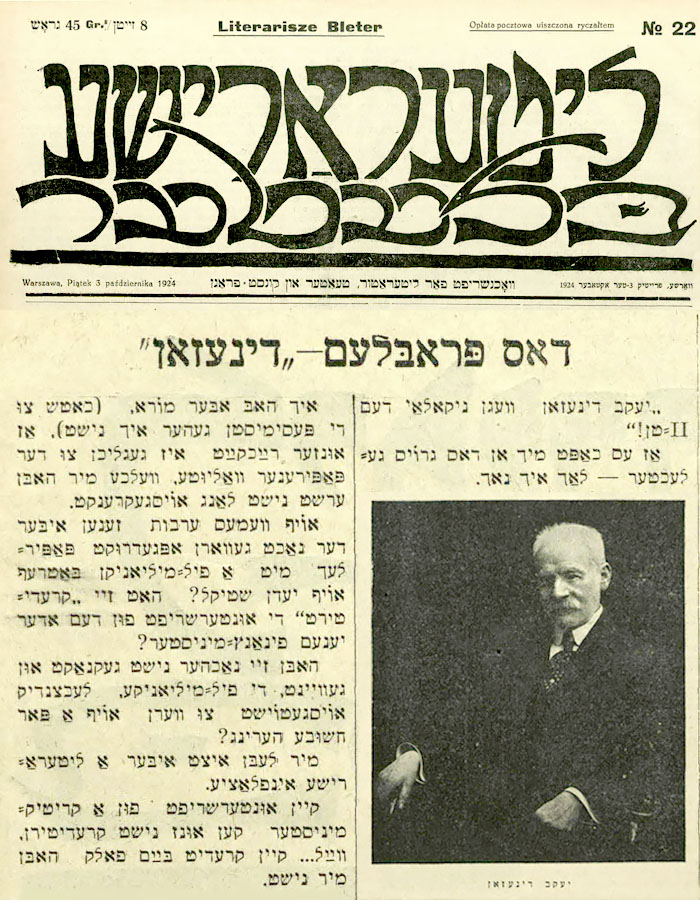

“ . . . Jacob Dinezon regarding Nicholas II!”

When I break out laughing—I continue to laugh.

The great big letters stretched out like an exalted person’s fleas dancing around the sheet of a spread-out Yiddish American newspaper and, before my eyes, wrapped themselves around the above-referenced words. I had to believe—a question for Columbus—that Jacob Dinezon, in his old age, became a political card-carrier.

When did that happen?

Once it did happen. [See “Samson Solomon and His Horses.”]

But we ourselves, those of us from Warsaw who knew Dinezon well, don’t we, until this day, make a Columbus joke of his name?

Various tales of wonder will be told about him: He was certainly an uncle to poor little Jewish children. He somehow belonged to the great Peretz. And a literati? Yes, he was that too. But in the past, quite some time ago.

For some reason, there is embarrassment in discussing Dinezon the writer in the bright presence of our highly developed literature.

So it may also be Columbus-esque to expose a “Dinezon” problem.

Not some tormented tales of wonder with which one needs occasionally to disturb a forgotten writer in his tomb. Because exactly as the expression goes, we will also lie in the ground at some point. No!

Dinezon actually hangs suspended over our modern abyss like a great bent question mark.

Where have you gotten to, little children? And how will you, poor things, get out of here?

Yes, if one has crawled off into an obscure corner—there is no doubt about that.

A little while ago, there was a hullabaloo among us: Yiddish literature is in decline.

Clearly, there were complaints about the “folk” and why it was deserting us.

At that time, I even tried to turn the fur over onto its other side. Not that the folk were deserting us, but that we were deserting the folk. Within the framework of those discussions, I was unable to be more prevailing.

Now comes the opportunity to have an exchange about this theme.

Until not very long ago, we maintained that our literature—may the same be so for whoever wishes us well—blossomed and grew. Now optimists think this way as well.

And indicators?

Who in Dinezon’s times knew about Yiddish publishers? About Yiddish dailies and journals that print literature?

And even in Peretz’s times, who would have dreamed that a weekly dedicated to literary matters would become so popular? (Here I’m referring to Literarishe Bleter.)

Certainly, we are getting richer.

But I’m afraid that just recently, to our dismay (though I don’t belong among the pessimists), our richness stayed at the “paper value.”

On whose guarantee did little papers get printed overnight with a face value on each one of multi-millions? Were they “accredited” by the signature of this or that finance minister?

Didn’t they afterward bang and weep, the multi-millions yearning to be exchanged for a few substantial herrings?

We are now living through a literary inflation.

No signature from a critic-minister can accredit us because . . . we have no credit among the folk.

There used to be a curse: “May you be a Polish millionaire!” With respect to spiritual credit, one can insult someone by saying, “May you be a modern Yiddish writer!”

Even in better times, our modern books aren’t snatched up, but pushed aside. In the best circumstances, they’re shoved into two thousand hands. Such luck: We have the mechanism for this (exceptions will yet be discussed).

Dinezon was snatched up in his day by the dozens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of copies, and thirty or forty years ago when the state of Jewish society was in perpetual reformation!

And this particular, frail Dinezon, the softhearted one with a feminine soul—he earned, in truth, the most consistent folk credit. He was the true folk-writer.

It wasn’t the street that read him but, really, the folk. Pious mothers, dreamy daughters, bearded fathers—he was read by the entire family. The only ones unable to enjoy Dinezon were the dry-bones awaiting resurrection who sought in books a commonsensical matter, a secular philosophy. He was read by hearts, Jewish hearts.

He attained the level that Mitzkevitch [Mickiewicz] so longed for when he tasked himself with the writing of “Pan Tadeusz.” He, Mitzkevitch, who stayed in foreign parts, among the elites, wanted the reparation of a simple heart, of a folk’s heart under a straw roof somewhere at a little window in the country.

Mitzkevitch longed for this—Dinezon attained it.

Where lay the secret of Dinezon’s ability to draw people in? Certainly not in that which we now call art and which is truly a tremendously boring thing for the broader masses. Dinezon was a folk artist, and this is something that we, with our present refinement, have no ear for whatsoever because we are all either native or induced introspectives and narcissists in a smaller or greater measure.

We had two true folk writers: Dinezon and Sholem Aleichem. No one imagines putting these two writers on the same plane. Yet it is this way: in the main achievement of their artistry, they are comparable.

Dinezon, the weeper, and Sholem Aleichem, the clown. Both move us with the same theatrical method. Both wrinkle the face of the folk and force it to play along. The first—to weeping. The second—to laughter.

Don’t discount the sentimentality of the art.

Real sentimentality is just as warranted as real humor. Both methods are primitive ways to create an effect. If they emerge from an artist’s natural characteristic, then their effect is—art. And as this is the shortest way to an effect, it is folk artistry.

You will just as naturally burst out weeping with Dinezon as you will naturally burst into laughter with Sholem Aleichem.

The folk hate to remain unmoved. Naturally, with tears alone, Dinezon would achieve nothing if he didn’t have the means by which to justify the tears.

If Sholem Aleichem is, according to our present-day measure, a greater artist of word and prose, one must, to fairly give Dinezon his due, remember two things:

First, the skill of genuine humor lies in the word and the phrase and also in the simple construction of the short element that contains in its entire architecture a big laugh. One can’t laugh for hours without hysteria.

Second . . . Dinezon’s pure literary merits have become so alien to us because, after him, we didn’t have a single writer who could repeat the same qualities.

Namely, Dinezon was a born romantic, and we don’t have any born romantics in this new age.

Sholem Aleichem doesn’t rise to Dinezon’s level in the artistry of writing a novel. Dinezon is the improvisational novelist with a natural long breath. Dinezon was able to sit for an entire twenty-four hours at his writing desk with the same unrelenting shake of his pen.

Don’t look at the antiquated style of his novels, at the pale heroes, at the asides.

I’m not going to recommend Dinezon as an example in all respects. His novel, however, has within it what none of our modern novelists have: natural inhale and proportion. This means a balance of all the parts of the long story while bearing a completed one in mind that he keeps pouring onto the page.

Our modern novelists are capital-writers in comparison to him. The capital swallows their breath. The accidental, colorful placement that is eternally rushing after the “genuinely artistic” moment pushes them out of proportion, and the reader has no straight, outstretched, long cord with a predominant tone. And this is due to the fact that our novelists were not born novelists but became so, and subsequent to a trait that Dinezon had: the naïve belief in the storyline and the naïve belief that a novel is itself a telling of a heartrending drama.

It is with this particular trait that Dinezon, the frail person and unassuming artist, won over the hearts of hundreds of thousands of Jewish readers.

Readers? Can we indeed speak about such a large number of Jewish readers?

We have a problem with readers. Him, the folk did read.

So what do I specifically mean by the “Problem of Dinezon”?

Peretz and, even before Peretz, Mendele adapted the European style into their writing. They placed a cornerstone of a literature comparable to the most distinguished, a literature for readers, the particular type of person with an interest in a well-written work.

Essentially, literature is considered by all peoples not as a folk entity but as a cultural-spiritual growth. Slowly and measuredly, literature infuses itself into ever-wider levels, along with the growth of the cultural-esthetic need of ever-widening masses.

Many years will yet pass before every Pole or every Russian knows his most popular poets and writers. And I can easily imagine that in America, for example, should an attorney or a doctor be simultaneously a great ignoramus about English literature because he simply has no interest in it, he’s nonetheless able to make a living. That is, today’s average reader is a person with a special desire, with a book-need.

If we were to peruse the entire literature of the past century, from the most genial works to the most unassuming, we would understand exactly how to name this particular book-need for the average reader. This is a desire for a cultural-esthetic pastime.

Not only literature, but all of the art of the past century, appears for us under the emblem of cultural-esthetical amusements. The mistake that the artists made with this is that they themselves, at the suggestion of the marks-dictatorship, adapted the amusement element as the purist art form and, to the extent that they themselves were not governed by a loftier idea, they simply created a special line of activity and convinced themselves they were making art.

The literature expressed itself in a distinctive productivity; this many books had perhaps not been written in the entire cultural history as in just this past century. The line of activity was accepted. Literature became a profession that pays. And, as with respectable folks, so it is with us. We also produced a literature-profession constructed upon the general reader. Here there was a bit of reckoning.

It turns out that making a living from literature is still a bit difficult for us. Several writers can be favored and sustained by the reader. But among us, candidates for professionals number no more than ten or twenty. Here is where the tragedy begins for the professional writer. (The folk don’t read us, the folk don’t sustain us—that is, we are extraneous. Yiddish literature is in decline, etc.)

From all of this, there is just this truth that either professional writing will die out, or we’ll allow ourselves to captivate the folk, or worse, the street.

Attempts to target the reader have already been made. But one can at least suspect the modernist in these particular attempts. The modernist in literature (as in art in general) is one who has ultimately divested himself of the suggestion of amusement as the seed of art. The modernist doesn’t have in mind someone’s entertainment. He gathers the seeds of pure art somewhere else among stones and wounds and the crazy laughter of the giant world-heart.

The modernist is angular, pointy; he doesn’t slide smoothly into the esthetic belly. And he doesn’t care that he is a tough morsel and that we’ll let him waste away on the shelf.

The only aspect of greatness that the modernist has in him (independent of his intellect) is that entertainment is not what is derived from his art, but worship. Not only for the folk is he strange; the average reading circle, the steady consumer of books, can’t digest him either.

If he’s read, it’s due to fashion, sensation, or scandal. Certainly, there will come a reader who will understand him, and this understanding will also contain an esthetic enjoyment but no longer amusement.

But the modernist will not feel relieved by this because if the reader already understands, then who knows if he’ll have transcended the modern artist, or if the modern artist will not then be too old or frail for him? The bottom line? The milieu affected by the modernist is, up to now, very tight, tighter, much tighter than the average reading milieu.

And here is the tragi-comic situation of the modern writer: On one hand, he himself consciously departs from the well-trod style and makes himself incomprehensible. On the other hand, like every artist, he suffers from a lack of popularity, and the more honest he is with himself, the less hope he has of becoming popular.

He will certainly not lower himself to the street-level taste, so he is left with locking himself into his tight milieu, proclaiming that literature, like every art, is a private matter that each one of us sings for himself, introspectively for himself, and that everything that is for people, for the wider public, is already compromised, not pure, not holy, amusement.

One thing is the half-childish, half-artistic yearning for popularity, and another is the serious thought given to the goal of creativity. And pondering is what the true modernist does more readily than the average writer.

Greatly productive he is not. (One can provide many examples from our little world, where literary productivity is a simple product of the demand for accessibility.) So he has time to think.

And while pondering, one may sometimes arrive at this conclusion: One must cast off all the tinsel and “isms” in which a modernist artist is occasionally involuntarily trapped like a fly in a spider web. So one thing remains:

Art is a profound matter. It cannot be turned into a game. Art is a higher truth.

A belief is currently floating in the air that “folk”—as a large homogenous collective—is also a serious matter. And this specific collective is the bearer of the higher truth.

Could there be a way, an opportunity to directly toss the seed of individual higher truth, the seed of art, over the heads of snobs in the narrow or wider reading milieu to the true, intuitive sworn judges—directly to the folk?

Couldn’t there be found a language—as paradoxical as it might be—a language that the modern writer would begin speaking to an auditorium of many millions?

Is this so wild an idea?

The tinsel of the nineteenth century has long been cast off. If only it could manage to get out of the spider web of the “isms.” Perhaps?

This is what I’m addressing: Problem . . . “Dinezon.”

You can call it what you will.