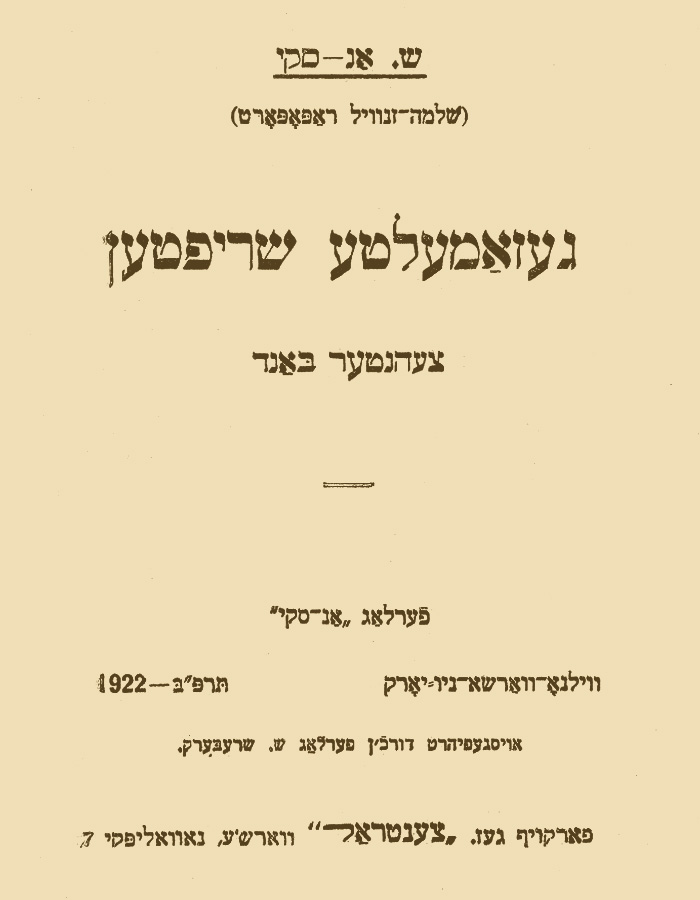

by S. An-ski

From Gezamelte Shriften (Collected Works)

Warsaw, New York: Farlag An-sky, 1920

Vol. 10, Pages 151–172

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Translated from the Yiddish by

Miri Koral

An-ski—Solomon Zaynvil Rapaport—was born in 1863 in Chashniki, White Russia. He lived in innumerable cities in Russia. Later, from 1892 to 1905, in Paris, Berlin; after 1905 often, for many months, in Warsaw. From 1918, always in Warsaw. There, he died in November 1920 and was buried in the Gensher Cemetery, near the graves of Y. L. Peretz, his most exalted friend, and Jacob Dinezon. Over the three gravesites is Abraham Ostrzego’s large artistic tomb. It is called Ohel Peretz (the Peretz Monument)—the holy scion of modern Yiddish literature. Poet, author of the Bundist “Anthem,” storyteller, dramaturge, and author of the popular and international Yiddish play “The Dybbuk,” which was first staged in Warsaw. One of the greatest, perhaps, the greatest collectors of folklore among Jews. Whenever he was in Warsaw, Peretz’s home was his home. And in the end, Peretz’s last home was An-ski’s last home.

“Peretz in His Last Year”

Right after my first acquaintance with Peretz in the year 1906, I was in Warsaw, where I was able to see Peretz in his daily life, in his usual surroundings.

In recent years, Jewish-nationalist-leaning intelligentsia began to organize their homes in a Jewish manner, in the Jewish style. On the walls, they put copies of Jewish images that were nearly the same everywhere (“Bad News,” “…Diaspora,” or something similar). On the tables, all sorts of Jewish objects made by Bezalel.

In Peretz’s home, I found none of these usual Jewish images, though it was the most Jewish dwelling I’ve ever seen. On every wall, in every corner, were Jewish paintings, etchings, sculptural groupings, bas reliefs, and other Jewish art objects. Among them were artistic dedications and anniversary presents, and old Jewish antiques. All the new works of art were originals, accomplishments of Jewish artists with whom Peretz was closely associated and helped to get out into the broader open world. One glance into the dwelling was enough to comprehend that here lives a person who stands at the center of the new Jewish culture, which flows through and deposits herein one of its elements.

In Warsaw, I became personally acquainted with Jacob Dinezon, with whom I was already acquainted through correspondence. I met him at Peretz’s place, or Peretz took me to him—and thereafter, I nearly always met them both together. And the more closely I became acquainted with them, the more profoundly I felt their intimate friendship with each other, until in my mind—and also in my heart—they became inseparable. One without the other was unimaginable.

There is a folk expression about the highest form of friendship and love between two people: “One soul in two bodies.” Regarding Peretz and Dinezon, the same expression could be said exactly the opposite: “Two souls in one body.” It is hard to imagine two characters, two individual identities, being so different from one another as were these two friends who were intimately linked and inseparable for years.

Peretz, with his sparkling, wonderful, intelligent eyes, his lively gesture, and his blazing and brilliant words, always roused in me the image of an enormous, precious, multi-faceted cut diamond. Like a diamond, the man was pure and luminous; like a diamond, he sparkled at the edge of every facet; like a diamond, he was strong in his opinions, and also, like a diamond, on some other occasion, he would sharply cut others who stood in the way of his lofty goal. Dinezon—with his placid gentleness, with his affectionate gaze which emanates with a continual tenderness, with his compassion and devotion, and his perpetual readiness to devote himself entirely to another; Dinezon, who is inherently incapable of uttering a sharp word, of causing anyone the slightest sorrow, was in many ways the opposite of the stormy, fiery, mighty Peretz, and both friends were as if joined in one body. There wasn’t anything, no literary plan, no accomplishment, no idea from one that the other didn’t know about. Both lived with the same life, with the same interests, the same joys and worries. In Peretz’s house, Dinezon was the same master as Peretz. He knew where every little paper lay, often finishing Peretz’s letters without asking him.

“Peretz, why haven’t you responded to my letters,” I asked him once.

“I figured that Dinezon replied.”

Replied what?—This, Dinezon evidently must have known as well as Peretz himself.

Their closeness even surpassed the level of friendship. One encounters such an intimate bond only between an old married couple that has lived together for half a century in love and constancy, and thus, in contact with one another, losing the boundaries of their own sense of “I”.

And apart from Dinezon—no one! Not one close person did Peretz have near him. Standing at the center of the self-generating Yiddish literature, almost of the entire new Yiddish culture—Peretz was terribly lonely. This was a great tragedy for this extraordinary man.

Seeing himself the spiritual leader of entire generations of Yiddish writers, feeling the great responsibility of the position that he occupied—Peretz didn’t have any social circle, felt no solid ground under his feet. Everything was in chaos. Unripe, unorganized, about to be hindered, to disappear. And Peretz himself had to cast himself in all directions, exert himself in all the situations. He always had to tear himself away from his artistic endeavors and appear as a publicist, a critic, a popularizer, an editor and publisher of “Little Papers,” manuscripts, weeklies, anthologies, arranging meetings, and so forth. But more than anything, he gave away time and energy to the young writers. He nurtured and raised entire generations with literature. Nearly all of those who now have name recognition in Yiddish literature went through his tutelage and should thank him for their literary upbringing. And as much as he was sharp and strict with those hundreds and thousands of young folks who plagued his head with talentless scribblings, he was that much more tender and liberal with those whom he perceived as having a spark of talent. To them, he devoted his time, his work, his support, and helped them set foot in the literature.

With Peretz’s death, it wasn’t only Yiddish literature that was orphaned but also the entire generation of Yiddish writers!

-After that first arrival in Warsaw, I was there a few more times. Two or three times Peretz was in Petersburg—and each time, we became closer to each other. But our friendship strengthened about three or four years ago when I organized in 1911 – 1914 the Jewish Ethnographic Expedition, in which I began to travel around cities and towns to gather folktales, legends, songs, melodies, and the like. Peretz and Dinezon were captivated by this undertaking. Each time I was in Warsaw, Peretz would “sit me down” to tell him Hassidic stories. Often I would sit for hours recounting to him one tale after another. He listened and could not get enough. I thereby had the opportunity to observe how the creative work arose from Peretz’s soul. In fact, while I was in the midst of telling the story, Peretz had already absorbed it, assimilated it, discarded the non-artistic elements, added new ones, and merged it with details from another tale. And I hadn’t even had time to finish it when Peretz was already telling me the same story, worked over into a “folk-style story”, which was as far from the first version as a cut and polished diamond is from a rough diamond crystal having just been dug up from the earth. The following day, one such story was already written and a few days later printed with the dedication “An-ski: The Collector”.

Peretz and Dinezon were so interested in the expedition that both decided to take part in it and to travel with me for a couple of weeks around the shtetls. For two summers in a row, while Peretz and Dinezon were guests at the summer home of B. A. Kletzkin, we corresponded about this. I waited for them but received a dispatch that certain unfortunate circumstances (I think Peretz’s health condition) did not allow them to travel.

The last time I saw Peretz was at the end of 1914 while I was visiting Warsaw for two months in November and December. For several weeks during this time, I lived at Peretz’s place.

It was a terrible time. Warsaw, which had just survived the turbulent arrival of the Germans in Poland during the days of October, was preparing for a new, even heavier attack. The enemy was already at Sokhotshov (sp?), by Bolimov. In Warsaw, the cannon fire was noticeably heard like distant thunder, while airplanes flew over the city dropping bombs. The city was full of soldiers, and the streets were packed with military wagon trains of loaded carts, medic-wagons, and artillery. Life in the city had reached the highest level of tension.

But for us Jews, all this, the danger of land-and-air battles, was pushed to the side in the face of the terrible misfortune that spilled onto the Jewish populace of the surrounding cities and towns . . . Every day, hundreds and thousands of refugees would arrive; driven out, they would arrive on foot, unclothed, barefoot, hungry, frozen, terrified, and helpless. And all around, churning and raging even stronger, was the Polish war against Jews: the incitements, libels, and denunciations. Every day brought new terrors, new tribulations, new violations, and even worse were anticipated.

It was in this hellish inferno that Peretz lived the entire time, the war having completely ruined him materially…In addition, Peretz still worked for the organized Jewish Community, where entire homeless and lost multitudes gravitated for help…

The horrible national catastrophe suddenly weakened Peretz’s fortitude. His health condition was his undoing. When I arrived around the middle of November, I immediately perceived what an awful change had occurred with him.

Peretz hated to speak about his own pains and illnesses and wouldn’t succumb to any sickness. But in this case, he was unable to ignore his physical condition: he was always fatigued, depressed, and barely able to leave the house. Several times when we went for a walk, he had a heart attack and had to immediately return. At night, the slightest noise would awaken him—and he could no longer go back to sleep and then was tired and sick the entire next day.

And what made an even greater impression on me was the complete change in the condition of Peretz’s spirit. I witnessed a different Peretz: shattered, shaken up. He had lost his certainty. And in his eyes appeared quite a different expression: an tentative question, as if he were searching and seeking an answer for what was taking place.

His approach to “Jewish Petersburg” had entirely changed. When before, he had not given it any value because his work was not an “inward Yiddish” but an outward one. Now he listened closely to what was being done in Petersburg, offering his opinion about the direction of the work.

Naturally. Peretz devoted his entire time and his energies to the homeless. He established in Hazamir, where he was the director, a home for several hundred refugees and concerned himself with ways to help them. With openhandedness, as he was wont to do, he donated for a lottery for the homeless all the beautiful and expensive gifts that he had received for his (writerly) anniversary celebration and from his admirers.

But this entire labor and all the sacrifices didn’t calm Peretz one iota. His tired, sick heart ached, was soaked in blood, and his enormous, forceful spirit was always seeking an answer to the historic destruction in Jewish life. The first day I arrived, we had a long talk about this situation. And from Peretz, I heard words drawn from the bitter and potent despair of humanity.

And when I returned to him late at night, I found him at his writing desk, pen in hand. Without lifting his head, he said to me:

“Sit, I want to read you my translation of Ecclesiastes. I’ve been working on it these last months.”

And he read to me, in my opinion, the most musical work that he ever created: his Ecclesiastes. And I felt that his broken spirit did not delve into Ecclesiastes by chance, as in hevel havolim (nothingness), there are powerful and certain foundations: “Generations come, and generations go, and the world remains eternal.” I felt that here he was seeking an answer to the horrible question relevant to these times.

I deliberately asked him whether he was planning to translate the Book of Lamentations. He grimaced.

“No. A lament without images, without a thought to the future.”

And the next day, he told me:

“I am very happy that you came. You will pull me away from my work, as I need to forget about it for several days in order for me to rework it again.”

And a few days later:

“I was mistaken. I figured that I would tear myself away from my work for only a few days, but it turns out that I have lost the desire for it; the interest isn’t there…”

A day later, he read to me his story “Nehila [the closing service on Yom Kippur] in Hell.” When he came to the place where, through the cantor’s melody, all the sinners are freed from hell, but the cantor himself remains there, he stopped.

“And how will I end the story?”

“I don’t know.”

“I don’t know either.”

And he actually didn’t finish it.

The second day of my arrival, he called me to go to Hazamir, to the homeless.

“The homeless are not interesting,” he suddenly said with sadness. “Usually, poor Jews that want to eat, want a handout. What’s interesting here is the person who sacrificed himself for their sake, may we not experience their plight. This is a rare individual; take a look at him. And even more interesting are his children; it is to them that I go.”

This is how Peretz’s broken spirit agitated itself from the ancient eternal Ecclesiastes to the living hope of the people, to the children, that gave rise to dreams of an opportunity of being rescued from the cauldrons of hell. It is possible that the mighty spirit of this extraordinary person found an answer to the terrible problem in Jewish life and conquered the doubts, but the sick, tired heart did not last.

And Peretz departed from us.

He left us an enormous and immortal legacy, but the most beautiful, most refined, most musical poem—Peretz himself—was lost to us.