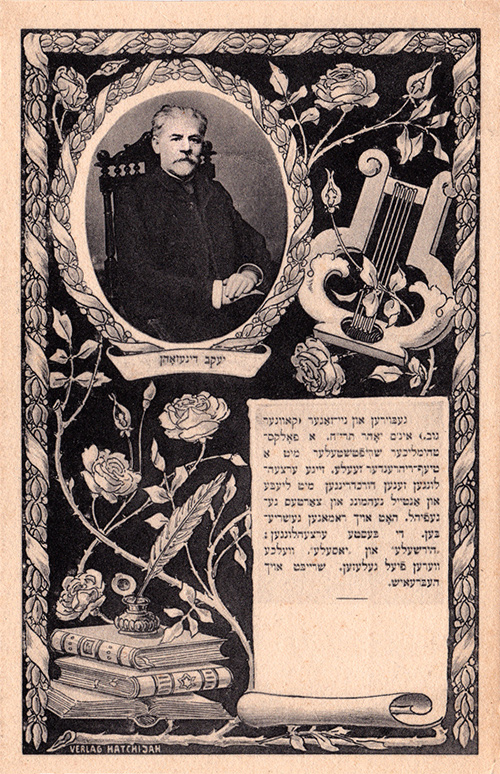

“It seems that in every place and in all times the Jewish heart is filled with troubles. One just needs to know the right word or the touching melody, and the thick ice that forms around the Jewish heart by cold life breaks open and tears pour out.” —Jacob Dinezon, Memories and Scenes: Shtetl, Childhood, Writers, trans. Tina Lunson

1851

Jacob Dinezon is born in Nay Zhager (New Zhager) in the Kovno Region of Lithuania. [Many biographical entries list Dinezon’s birth year as 1856. A few suggest 1852. An 1858 record in the LitvakSIG All Lithuania Database – Part 1 shows the name Yankel Eliash Dinerzun, age seven, and the Yiddish newspaper, Haynt (Today) of August 1919 reports that Dinezon was 68 years old when he died, which makes the year of his birth 1851—the year we use here.]

Young Jacob grows up in a comfortable Hasidic household with a doting mother, Pessie, and a scholarly father, Binyumin, who is often away on business. He has two older sisters, one younger sister, and a brother who dies in early childhood.

1855

At four years old, Dinezon is enrolled in cheder to begin his Jewish education learning Torah. A small, bright, gifted student, he suffers through a series of old-fashioned cheder teachers who are quick to use corporal punishment on their young charges. Later, Dinezon wrote about one teacher in his “Recollections,” published in Der pinkes (The Book of Records): “He would beat without a reason and chopped our backs like cabbages. Even in the evening when he dismissed us, he would distribute advance payment for the next day. The advance was particularly large on Fridays, so we would remember him until after the Sabbath.”

“I began to write when I was barely ten years old. Why I wrote I don’t exactly know. But for as long as I can remember, everything which would move another to cry out, to speak, to complain, or even to laugh, moved me to take the pen in hand and write . . . until my awakening heart spent itself and became peaceful.” —Jacob Dinezon, “Jacob Dinezon’s Letters” with commentary by S. Niger, Di Tsukunft (The Future), trans. Jane Peppler (NY: 1929), pp. 620-621

1863

Dinezon enters the yeshiva at age twelve.

Shortly thereafter, his father dies, and he is sent to live with an uncle, Isaac Eliashev, in the Russian city of Mohilev (Mogilev) on the Dnieper River.

1866

Dinezon is enrolled in a prestigious Jewish school that embraces the spirit of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment). He learns Russian, German, mathematics, world history, and science.

1867

At sixteen, Dinezon lives and studies in the home of Simcha Zuckerman, a pious man of newly acquired wealth, in the city of Mir. Here Dinezon helps Zuckerman build a library of religious books and Enlightenment literature published in Hebrew. While translating a weekly Hebrew newspaper for Zuckerman’s family, Dinezon comes to realize the value of Yiddish as a way of communicating Enlightenment ideas to Jews who are not literate in Hebrew.

1868

Dinezon enters the employ of a wealthy and prominent family in Mohilev named Hurevitsh. Starting as a Hebrew tutor, he is soon promoted to bookkeeper and then to manager of the family business.

He becomes a trusted member of the Horowitz household, and Bodana Hurevitsh, the family matriarch, becomes a second mother to him.

The Hurevitsh home is a gathering place for disaffected young people struggling to break away from the restrictive customs of traditional Jewish religious life, including an insular worldview, rigid gender roles, and arranged marriages. Here Dinezon finds poignant and emotional material for his future novels.

During this period, according to the literary historian S. L. Tsitron, Dinezon falls in love with the Hurevitshes’s only daughter, whom he is tutoring. He escorts her on travels to foreign lands to study music, yet is never able to reveal his true feelings.

The relationship ends sadly when, at the request of her parents, Dinezon must travel to Vilna to make arrangements for the girl’s marriage to another man.

1876

Dinezon begins publishing articles in Hebrew newspapers and publishes scholarly brochures on scientific subjects, including “Thunder and Lightning” and “Rain and Snow.”

1877

With the manuscripts of two recently completed novels in hand, Dinezon heads to Vilna with an introduction from Bodana Hurevitsh to her sister Devorah Romm, head of the famed Widow and Brothers Romm publishing company. There, he meets the renowned Yiddish writer Isaac Meyer Dik, who assists him with the sale of his first novel, Beoven avos (For the Sins of the Fathers), for twenty-three rubles. Due to censorship, the manuscript is never published and ultimately lost.

To replace the censored book, the Widow and Brothers Romm publishes Dinezon’s second novel, Ha-ne’ehavim veha-ne’imim, oder, Der shvartser yungermantshik (The Beloved and Pleasing, or, The Dark Young Man).

This same year Dinezon moves to Moscow, where he works at a tea company for one of his relatives. While there he learns that The Dark Young Man has been published. The novel quickly becomes a great sensation, with the first ten thousand copies selling out quickly and several reprints to follow. The novel is so difficult to obtain that Dinezon must obtain a copy from a clandestine bookseller. About this first book, it is said that for many years, the names of the characters were household words as though people actually knew them.

“There was hardly a Jewish home where all the members of the family—old and young, male and female—had not read the novel and not shed hot tears of sympathy for the sufferings of the unfortunate Yosef, Rukhame, and Roza; while the name of the evil young man, Meyshe Shneyur, became the byword for hypocrisy, cruelty, and murder.” —Nachman Mayzel, “A Few Words About This Edition,” in The Beloved and Pleasing, or the Dark Young Man, trans. Tina Lunson (New York: S. Sreberk, 1928)

While in Moscow, Dinezon learns that his literary hero, the Hebrew writer Sholem Abramovitsh, is using the pen name Mendele Moykher-Sforim (Mendele the Book Seller) for the works he is writing in Yiddish. When Dinezon asks why Abramovitsh would use a pseudonym, the informant replies, “Would you wear your Sabbath coat to the shop on weekdays?”

1878

Despite the great success of The Dark Young Man with the general public, Dinezon is disappointed by the negative critical response the novel receives from the Enlightenment press because it is written in Yiddish and not Hebrew. At the time, Yiddish was considered a lowly language only worthy of the home, street, and marketplace. Hebrew was the elevated language of the religious scholar and enlightened intellectual. Dinezon was devastated by the criticism leveled at him for writing in the disdained “zhargon” (jargon).

Dinezon is also distressed by the sudden appearance of opportunistic Yiddish writers and their shamefully imitative works. In response, although he continues to write, he ceases to publish another Yiddish novel for thirteen years.

“I felt guilty for the whole flood of vapid and dismal novels drowning the Jewish reader. I couldn’t stop writing, but it didn’t cost me effort or mental strain not to publish the finished works.” —Jacob Dinezon, “Jacob Dinezon’s Letters” with commentary by S. Niger, Di Tsukunft (The Future), trans. Jane Peppler (NY: 1929), pp. 620-621

1882

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 and the accession of Alexander III lead to pogroms throughout the Russian Empire and the imposition of the May Laws, which intensify restrictions on Jews living in the Pale of Settlement. Jews are prohibited from residing outside of towns and boroughs, owning or managing real estate property or leasing land, and operating their businesses on Sundays or other Christian holidays. These edicts essentially dash any hope that Jewish writers will be permitted to engage in Russian cultural pursuits under the new Tsar.

1885

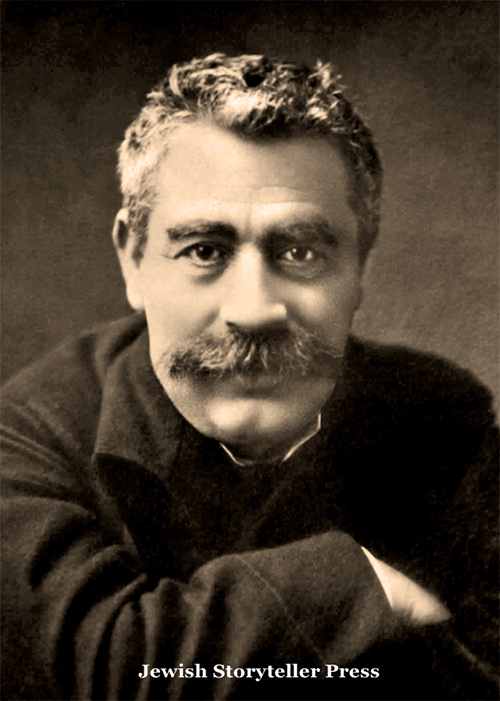

Dinezon moves to Warsaw to be closer to his older sister and her family. His small apartments at Nalewki No. 19 and later at Dzielna No. 15 become a gathering place for the city’s Jewish literary circle, and Dinezon becomes a mentor and advisor to many fledgling Yiddish writers.

1888

While visiting Kiev, Dinezon is arrested and jailed for several hours until his identity is verified and his papers approved by the authorities.

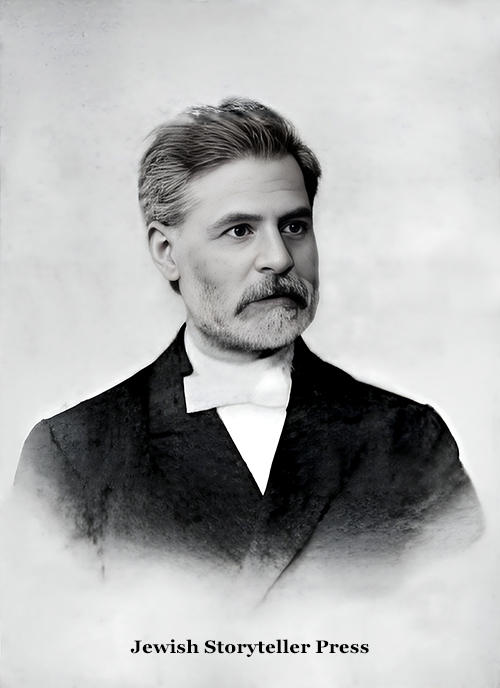

This same year, Sholem Aleichem comes to Dinezon’s small apartment to discuss his plan to publish a Jewish literary anthology. Also present are David Frishman and S. L. Tsitron. Sholem Aleichem’s goal, he says, is to elevate Yiddish literature.

Dinezon contributes advice and a short story, “Go Eat Kreplach,” to Sholem Aleichem’s new venture. Also included in the first volume is a long poem by I. L. Peretz entitled “Monish.” Peretz, whose law practice had collapsed following his disbarment by the Tsarist authorities, was just beginning to write seriously in Yiddish. Although Sholem Aleichem publishes the poem, he makes critical edits without first informing Peretz. This leads to a feud that lasts for many years.

When Dinezon reads “Monish” in Sholem Aleichem’s Di yidishe folks-bibliotek (The Jewish People’s Library), he corresponds with Peretz to express his enthusiasm for Peretz’s writing.

1889

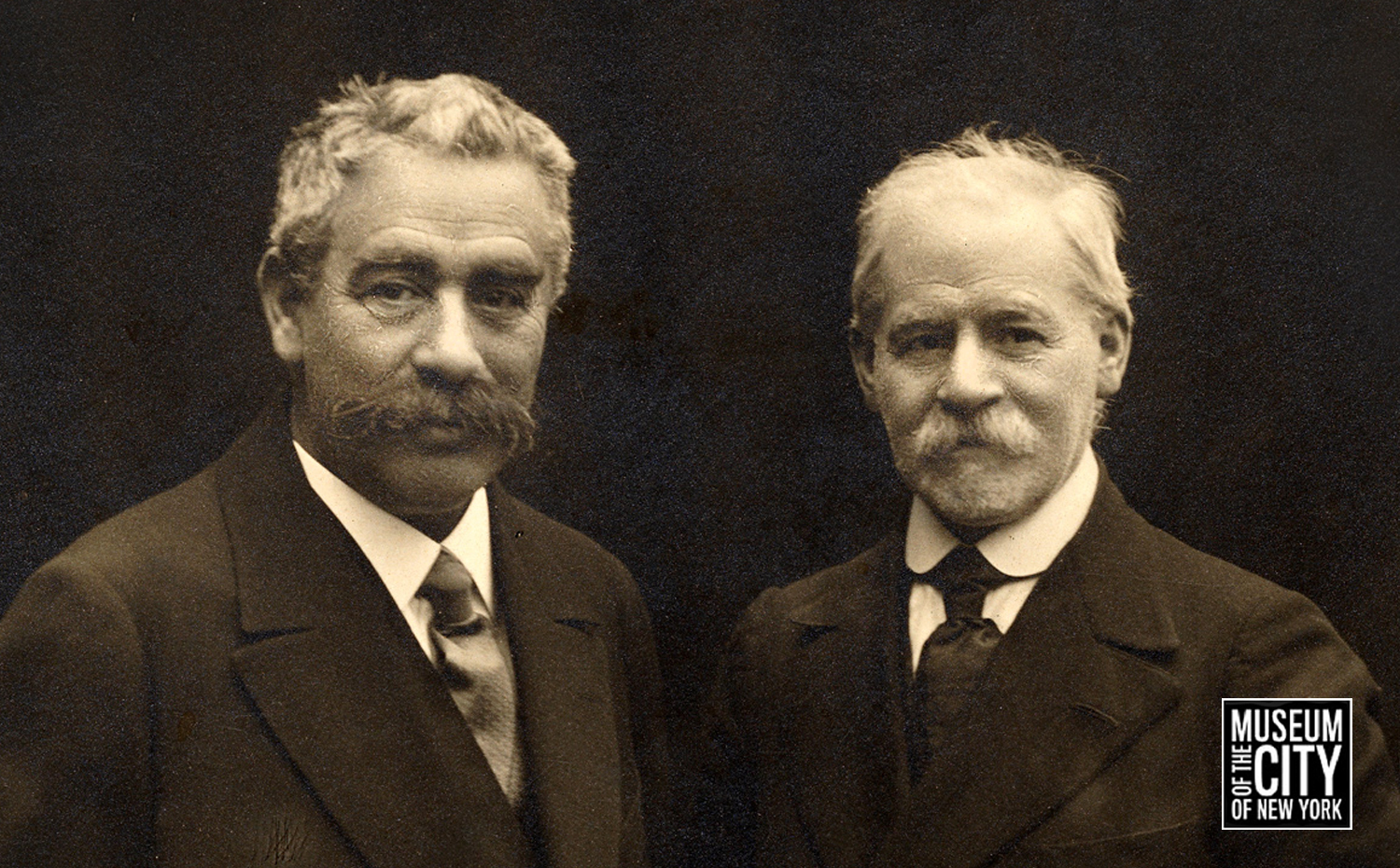

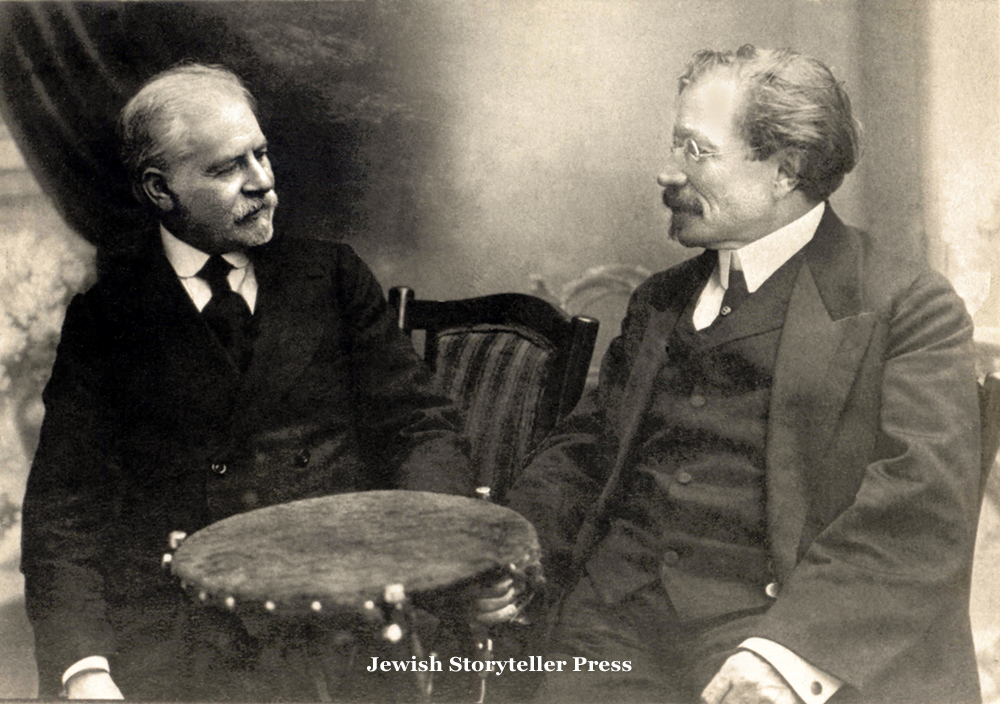

Peretz moves to Warsaw, where he finally meets Dinezon. They become inseparable friends.

Perhaps through Peretz’s encouragement, Dinezon begins to publish again. His book Even negef, oder, a shteyn in veg (Stumbling Block, or, A Stone in the Road) is published in Vilna.

1890

Dinezon pays for the publication of Peretz’s first book of Yiddish stories, Bekante bilder (Familiar Pictures), a collection of three short stories, “The Messenger,” “What Is Soul?” and “The Mad Talmudist.”

“Mr. Peretz writes not to flatter the coarse taste of the lower class of reader; rather, he wants to refine and improve him. So we are not being excessive in inviting the honorable readers—who are not yet accustomed to it—into a small Yiddish booklet to find something good in it.” —Jacob Dinezon, Bakante bilder (Familiar Scenes) by Leon Peretz, ed. Y. Dinezon, trans. Tina Lunson (Warsaw: Boymriter, 1890)

Dinezon intends Bakante bilder to be the first in a series of books in a “penny library” that will bring Jewish readers stories of substance in Yiddish. No additional books are published.

This same year Sholem Aleichem must cease publication of Di yidishe folks-bibliotek after suffering major losses in a Russian stock market crash.

1891

In partnership, Dinezon and Peretz begin publishing their own literary anthology, Di yidishe bibliotek (The Jewish Library), which runs until 1894. The name infuriates Sholem Aleichem.

At Peretz’s insistence, Dinezon’s book, Hershele, is published as a supplement in Di yidishe bibliotek.

With antisemitism growing in Russia and Russian-controlled lands and increasing deportments of Jews to the Pale of Settlement, Dinezon and Peretz make plans to settle in Argentina where thousands of Eastern European Jews are emigrating. Their intention is to start a daily Jewish newspaper, but their plans never materialize.

1892

Dinezon moves to Kiev to work for the Hurevitch family and becomes engaged in the city’s literary community, but a scandal perpetrated by a group of unscrupulous writers so embarrasses and alienates him that he can barely show his face on the street.

1894

Dinezon assists Peretz and David Pinski with the publishing of Yontef bletlekh (Holiday Pages) as a creative way of getting around the Tsarist ban on Jewish newspapers. Between 1894 and 1896, they publish seventeen issues.

1896

Dinezon returns to Warsaw, where he lives near his older sister Fayja Kac (Fayga Katz) and her family for the remaining years of his life.

1897

Dinezon writes an angry article that is critical of the German historian and biblical scholar Dr. Henrich Graetz for refusing to allow his monumental history of the Jews to be translated into Yiddish. Dinezon’s response is a powerful defense of Russian Jewry and the Yiddish language. Graetz ultimately acquiesces, and Dinezon goes on to translate three parts of the work, although a conflict with the publisher compels Dinezon to remove his name from the finished work.

1899

In February, his short story “Foolishness: The Community Goat” is published in two installments in Der yud (The Jew). He begins the tale about blind obedience to tradition with comments about the ongoing antisemitic Dreyfus Affair in France.

Dinezon’s novel Yosele is published in Warsaw. The heart-wrenching story about a poorly treated schoolboy has a profound effect on transforming traditional Jewish education at the turn of the twentieth century.

“Dinezon immortalized the abandoned, neglected orphaned child in his Yosele. That novel, snatched up eagerly as a critique of the old-fashioned cheder, seemed to all preachers of modern Jewish education as a true picture of the class division that had been built up in Jewish life in the nineteenth century, and as an urging for fundamental educational reform in order to place it on a foundation of fairness and goodness.” —Introduction by Samuel Rozshanski, in Yosele. The Crisis: Novels and Studies on the Jewish Literature by Jacob Dinezon, trans. Jane Peppler (Buenos-Ayres: Yosef Lifshits-fond beim kultur-kongres in Argentina, 1959)

Peretz is arrested while speaking at a Jewish labor workers’ meeting and is imprisoned for three months in the Tenth Pavilion of the Warsaw Citadel. When Peretz is released, he is ill and seriously malnourished.

1901

Dinezon spearheads a three-day celebration in Warsaw to celebrate I. L. Peretz’s fiftieth birthday and twenty-fifth year as a writer. To celebrate the event, Dinezon collects, edits, and publishes a volume of Peretz’s collected works.

During the celebration, a delegation from the Arbeter Bund (The Jewish Workers Union) presents Peretz with a written proclamation and gift: a book of Peretz’s stories that Jewish political prisoners had used to send secret messages to each other in the Warsaw Citadel. Peretz keeps the book as a prized possession, but Dinezon burns the proclamation to destroy any evidence of Peretz’s association with the outlawed Jewish Workers’ Party.

1902

Peretz suffers a near-fatal heart attack and is sent to the resort town of Marienbad, Germany, to recuperate.

In December, the Yudishe folks tsaytung (Jewish People’s Newspaper) celebrates Dinezon’s twenty-fifth year as a writer with a photograph and three-part Jubilee retrospective by Dr. K. D. Hurvitz. The literary critic Bal-Makhshoves (Isidor Eliashev) also commemorates the event in an essay published the following May in Der fraynd (The Friend).

1903

Dinezon continues to provide stories to Yiddish newspapers. His novella, Alter, appears in installments in Der fraynd (The Friend).

News of the Kishinev pogrom and massacre horrifies Russian Jewry and reverberates around the world.

1904

As the Russo-Japanese war rages in Asia, Dinezon has one of his most prolific years as an author. Appearing in the pages of Der fraynd alongside Sholem Aleichem, I. L. Peretz, Mendele Moykher-Sforim, and S. An-sky, Dinezon contributes short stories, holiday tales, non-fiction, and two novellas, Falik in zayn hoyz (Falik and His House) about an aging tailor who resists selling his deteriorating house to join his children in America, and Der krizis (The Crisis), a story about modernity’s effects on the lives of Jewish merchants.

On July 3, Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, dies in Vienna. Ten days later, Dinezon’s tribute to Herzl appears on the front page of Der fraynd.

1905

The Tsarist government lifts the ban against Yiddish theater. Peretz begins writing plays, and Dinezon works to bring Yiddish theater to Warsaw.

In January 1905, a failed Russian Revolution brings Cossacks and Russian soldiers to the city as the Tsar attempts to suppress the rebellion.

what you do not feel, do not write!

—J. Dinezon

1906

Dinezon is invited to America by Johan Paley, editor of the New York Yiddish newspaper, the Jewish Daily News. Dinezon declines the offer while Warsaw’s Jews continue to suffer under Russian oppression in the aftermath of the failed Revolution.

“Let me assure you that I fully appreciate your offer, but to make use of your steamer ship ticket is quite out of the question. My place is here with my people, come what may.” —Jacob Dinezon, “Evening Star,” Chronicling America, August 19, 1906, p. 5 (U.S. Library of Congress)

1908

Peretz and Dinezon sign an invitation urging participation in the “Conference for the Yiddish Language” to be held in Czernowitz, Austria. Although Dinezon does not attend, Peretz addresses the conference, which declares Yiddish, alongside Hebrew, as a national language of the Jewish people.

1909

In celebration of Sholem Aleichem’s fiftieth birthday and twenty-fifth Writer’s Jubilee, Dinezon organizes an effort to buy back Sholem Aleichem’s copyrights from the original publishers. The return of these copyrights allows Sholem Aleichem to earn much-needed income from the republication of his stories. Sholem Aleichem replies with a letter of thanks to “Uncle Dinezon.”

1914

The First World War begins. Again, in partnership with Peretz, Dinezon helps found the Home for Jewish Children, an orphanage to care for the many displaced children arriving in Warsaw from the Russian-German war zone.

With prompting from Dinezon, Sholem Aleichem and Peretz end their feud, and the three writers make plans to conduct a lecture tour in America.

The Germans enter Warsaw during the month of October.

An-ski stays with Peretz during November and December. An-ski describes the situation in Warsaw in his “Memories of Peretz and Dinezon.”

1915

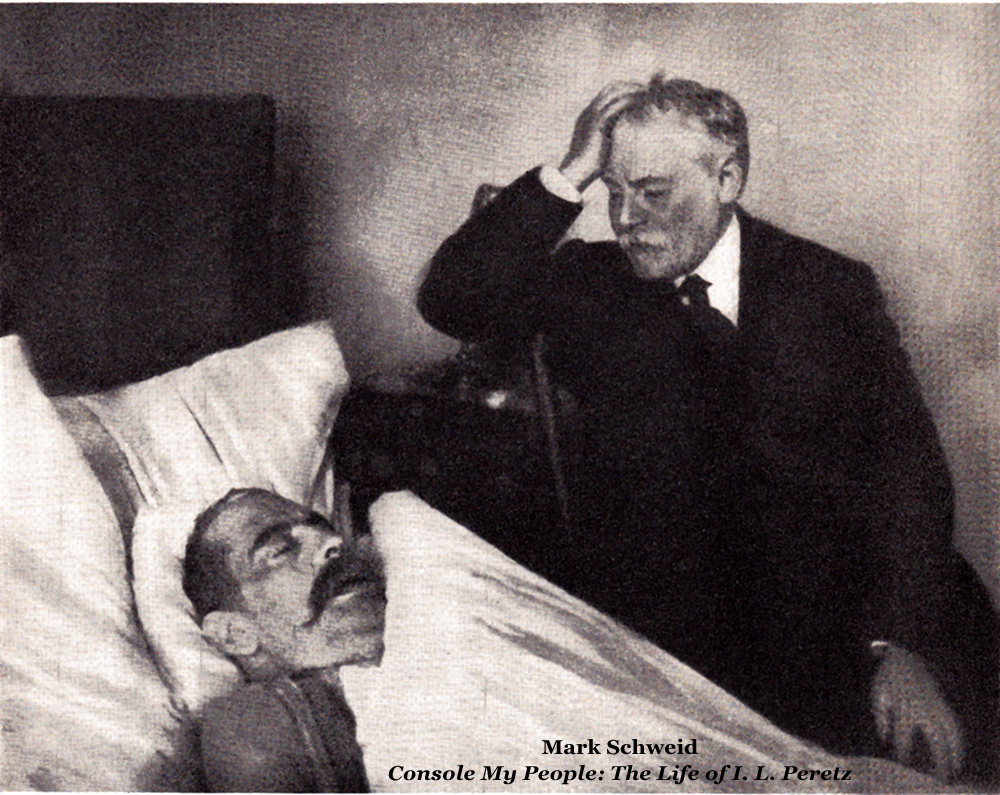

On April 3, during Passover, Peretz dies of a heart attack in his Warsaw apartment. Dinezon sits as a shomer (watchman) until his friend’s body is removed and transported to the cemetery. One hundred thousand mourners turn out for Peretz’s funeral.

“Quiet and simple was the mourning chamber in which rested the deceased body of I. L. Peretz. . . . The endless stream of visitors made it impossible for one to linger more than just a moment. The people kept changing, but the stream of quiet tears never ceased. The well-known writer, Dinezon, the dearest friend of the deceased, never for a moment left the dead body.” —A. A. Roback, I. L. Peretz: Psychologist of Literature (Cambridge, MA: Sci-Art Publishers, 1935)

1916

With Peretz gone, a grief-stricken Jacob Dinezon turns his attention to financing and nurturing Poland’s Yiddish secular schools movement.

On May 13, Sholem Aleichem dies in America. Over one hundred and fifty thousand mourners line the streets of New York City for his funeral.

1917

In the same year as the Russian Revolution, Dinezon’s friend Sholem Abramovitsh dies in Odessa.

1919

On Friday evening, August 29, surrounded by family and friends, Jacob Dinezon dies in his sister’s Warsaw apartment at Karmelica 29. Because it is the beginning of Sabbath and newspapers will not appear again until Sunday morning, news of Dinezon’s death is spread by word of mouth.

In a show of solidarity on August 31, the day of his funeral, Jewish mourners in the tens of thousands from all walks of life and political ideologies line the streets of Warsaw to express their grief.

His final wish is fulfilled when he is buried beside his friend I. L. Peretz in the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery.

“Even if Dinezohn had made no noteworthy contribution to Yiddish letters, his services in behalf of suffering humanity would have endeared him to the Jewish people. The fame of his work for the war orphans of Poland has gone far. Dinezohn’s schools, Dinezohn’s home for children, Dinezohn’s little orphan wards come to mind whenever his name is mentioned. He will long be remembered as a rare and great soul.” —The Sentinel, Chicago, Illinois, September 12, 1919, No. 11, p. 8

1920

S. An-sky dies on November 8 and is also buried beside Peretz and Dinezon in Warsaw’s Jewish Cemetery.

1925

On May 25, a grand monument by sculptor Abraham Ostrzega is unveiled in the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery to commemorate the tenth anniversary of I. L. Peretz’s death. Jews call it Ohel Peretz (Peretz’s Tomb). Poles call it the Mauzoleum Trzech Pisarzy (Mausoleum of the Three Writers) because Jacob Dinezon and S. An-sky also lie beneath its ornate granite edifice.

1943

Nearly the entire population of Jewish Warsaw is deported or murdered by the Nazis during the Second World War. Neighborhoods within the Warsaw Ghetto and the Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street are reduced to rubble and burned to the ground. Everything from Dinezon’s world is destroyed. Miraculously, the Jewish Cemetery remains mostly unscathed.

2019

A memorial event is held on August 31 in the Jewish Cemetery of Warsaw to commemorate the one-hundredth anniversary of Jacob Dinezon’s death. Organized by the Jewish Historical Institute as part of the Singer’s Warsaw Cultural Festival, barely a dozen participants show up for the service. Only three are Jewish.

While at the very same time in America, a Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof, based on Sholem Aleichem’s “Tevye the Dairy Man” stories, plays to sold-out crowds in New York City.

Jacob Dinezon is the optimist of our Yiddish literature. For him, evil is just a matter of chance, and he is confident that good will always triumph over the unfortunate accidents of life. The person who looks at God’s little world through the eyes of a faithful, devoted mother could not feel otherwise; he lives with a deep belief that within a shadow, one can find a thousand bright colors. —Bal-Makhshoves (“Man of Thoughts”), “Jacob Dinezon,” The Gathered Writings of Bal-Makhshoves, trans. Jane Peppler, (Washington, D.C.: S. Shreberk, 1910), vol. 1, p. 113–120