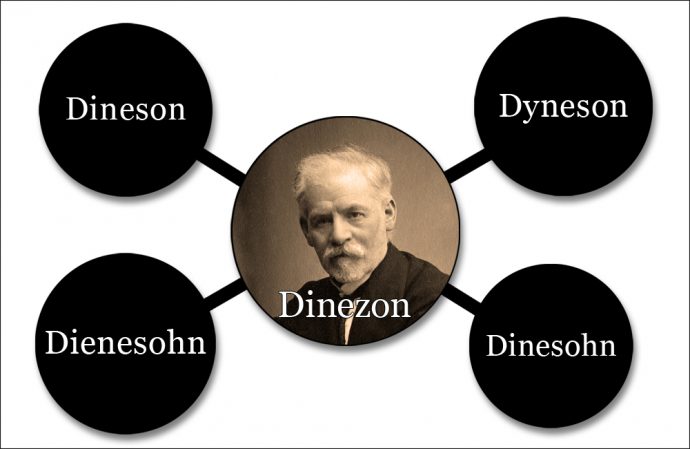

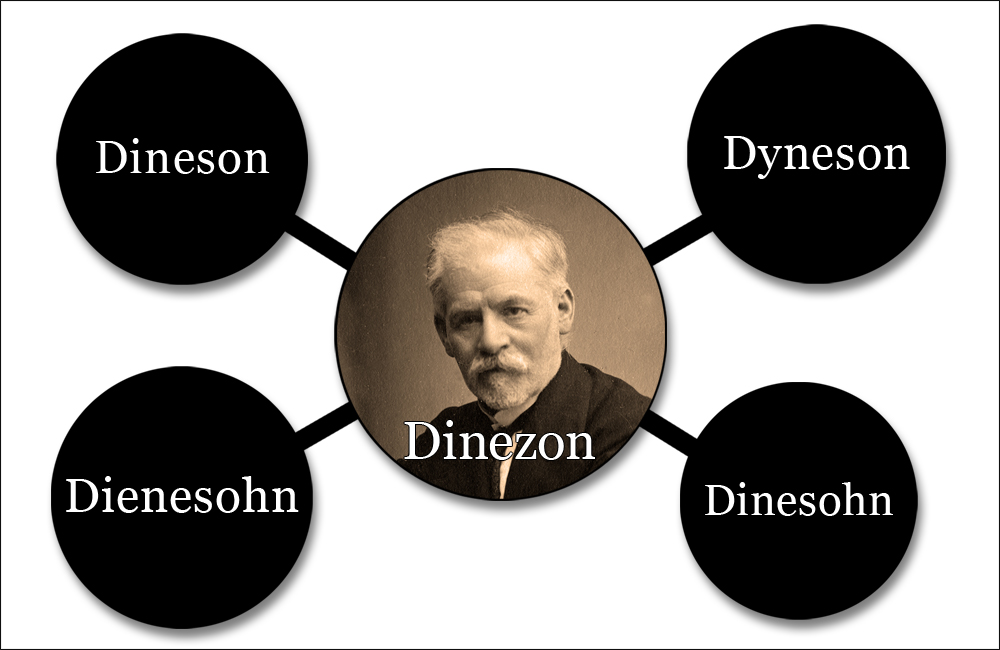

I can’t remember the exact moment when I began connecting the dots that led me to the realization that the name Dineson, Dinesohn, Dienesohn, Dyneson, and Dinezon all belonged to the same person.

(Later I would learn from Adam Teitelbaum that the spelling of this same name in Yiddish, the language in which he wrote, also appeared in multiple ways. Even his handwritten signature, which includes an “h” (ה/hey) before the final “n” (ן/langer nun), conflicts with the spelling of his name in many Yiddish publications.)

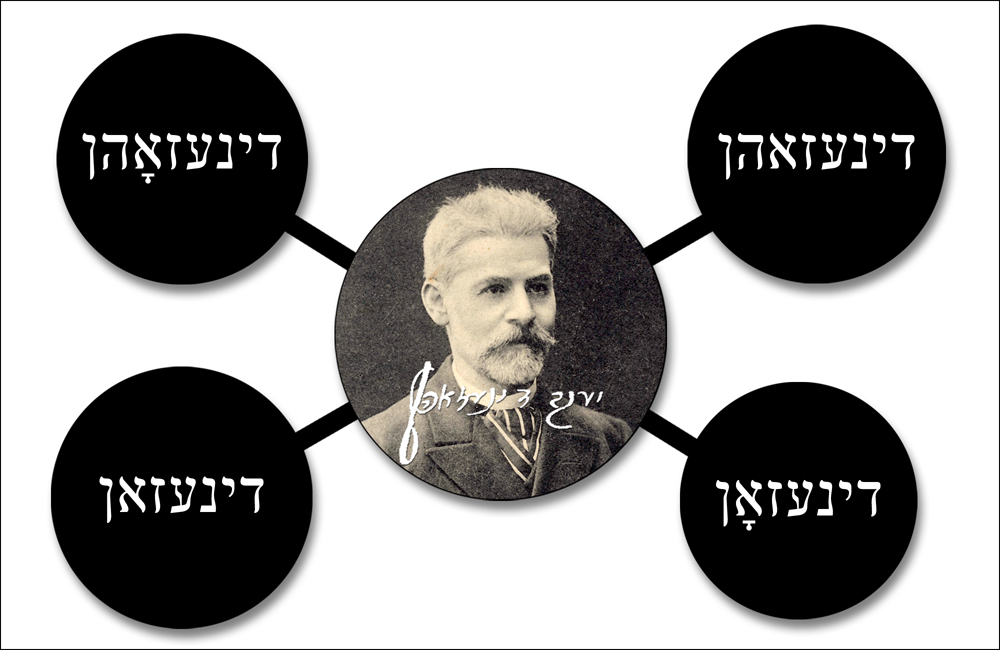

So imagine my surprise when all the spellings suddenly coalesced into a single person—a Jewish author who it turned out wrote the first bestselling novel in Yiddish, carried on a life-long correspondence with Sholem Aleichem, became I. L. Peretz’s best friend and confidant, and is buried beside Peretz and S. An-sky in a grand mausoleum in the Warsaw Jewish cemetery—the remarkable Yiddish writer Jacob Dinezon.

My re-immersion into Yiddish literature in English translation began shortly after my father of blessed memory passed away in 2001. My primary interest was I. L. Peretz, whose stories I had been introduced to as a teenager, and whose characters had haunted my imagination for decades. At fifty years old, I suddenly found myself searching for an avenue back to my Jewish roots, and my former love of Peretz’s stories seemed like a direct connection to the culture and values of my childhood which I so longed to recapture.

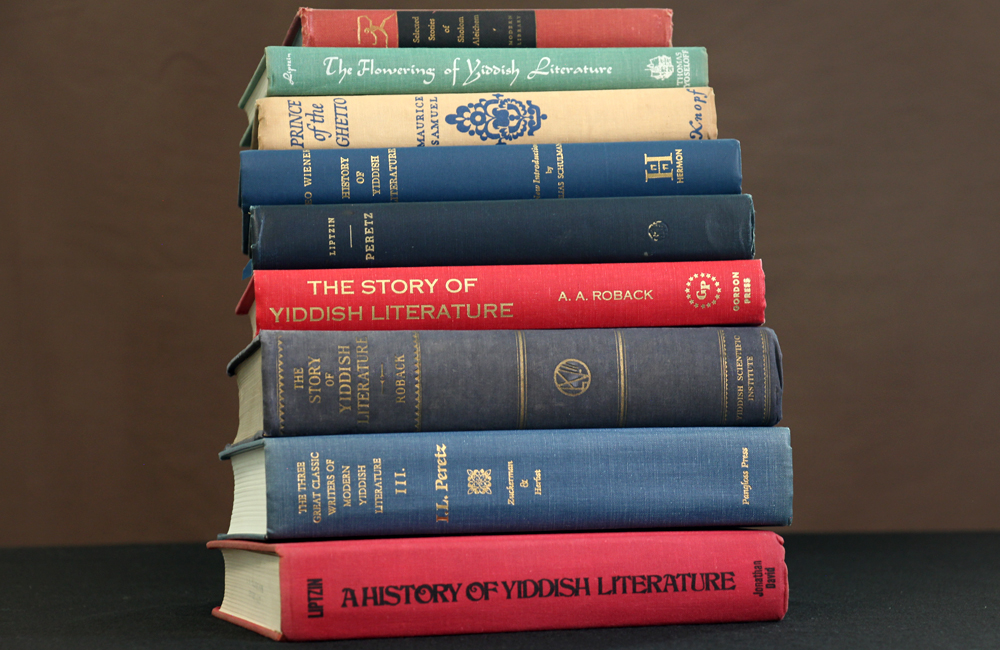

Over the next several months, I began assembling a small library of used books from eBay and abebooks.com. The musty, ragtag, multicolored collection included histories of Jewish literature and anthologies of English-translated stories by the two Yiddish writers who had the greatest impact on me as a teenager: I. L. Peretz and his contemporary and literary rival, Sholem Aleichem. The tall oak bookcases in my living room began to fill up with titles such as The Flowering of Yiddish, A Treasury of Yiddish Stories, I. L. Peretz: Psychologist of Literature, and The World of Sholom Aleichem.

As I immersed myself in these anthologies, histories, biographies, and memoirs—especially those by Peretz’s disciples in the first decade of the 20th century—I began noticing a name popping up here and there that I had never heard or seen before: Jacob Dinezon.

One of my earliest purchases was a multi-volume set called Three Great Classic Writers of Yiddish Literature: Selected Works in Translation edited by Marvin Zuckerman and Marion Herbst. The first volume is devoted to Mendele Mocher Sforim (Sholem Abramovitsh), dubbed “the grandfather” of Yiddish literature by the subject of the second volume, the Jewish humorist Sholem Aleichem. Sholem Aleichem proclaimed himself “the grandson” as a way of linking his literary lineage to Mendele. The third volume focuses on the works of I. L. Peretz, whom scholars have deemed “the father,” thereby completing “the family” of modern Yiddish literature. How can you have a grandfather and grandson without having a father in there somewhere? (Years later, the literary historian and biographer Shmuel Rozshanski declared Dinezon “the mother among our classic writers” to describe Dinezon’s tear-inducing, sentimental role in the development of Yiddish literature.)

As I was reading through the volume on Peretz, I came across a short memoir by the writer Jehiel Isaiah Trunk, “Peretz at Home,” translated into English by Lucy Dawidowicz. Trunk vividly recalls his first two visits to Peretz’s apartment in Warsaw, Poland.

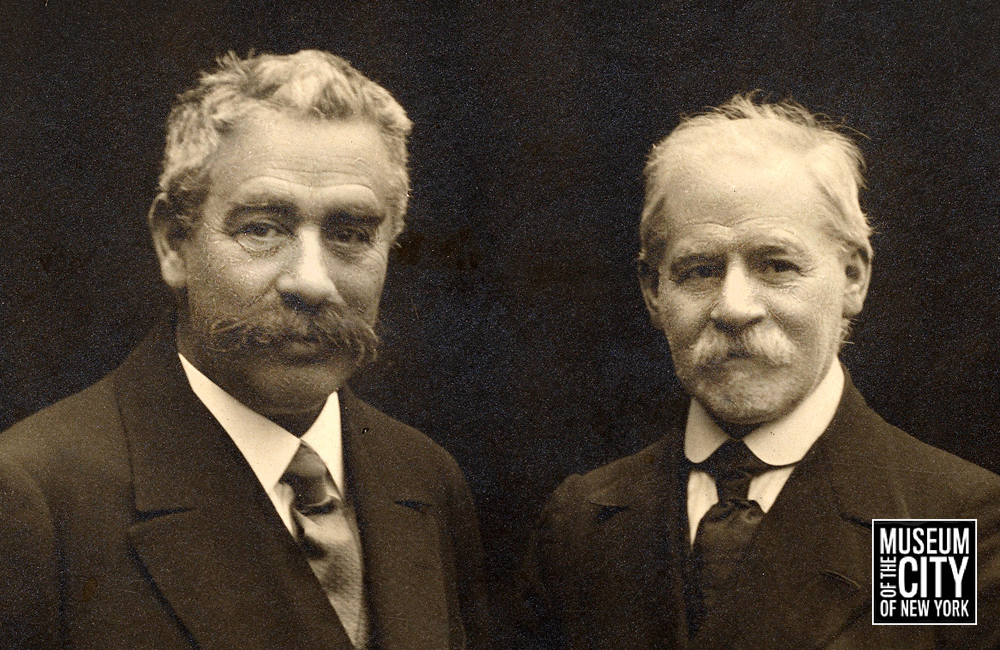

Trunk is warmly greeted at the door by Peretz who is wearing a silk smoking jacket and pince-nez glasses and is led into the famous author’s study. There he discovers a gray-haired and gray-bearded “dwarfish creature” sitting behind Peretz’s desk absorbed in rolling cigarettes: Jacob Dinezon.

Trunk writes, “Dineson turned around to inspect me. To him I was a new face, a young man in a kapote (a long black coat). As for me, it was with great awe that I looked at him. This gray, dwarfish man was the famous author of Der Schvartser Yungermantchik and of Yosele, a book over which I had wept a sea of tears. My mother had wailed aloud over it. And even hardhearted Grandfather Boruch, reading it, had broken into sobs and had groped for a cane to beat up Berl the cruel melamed (Hebrew teacher). More than ever, Peretz’s home seemed peopled with the figures of my secret dreams.”1

Another young writer with vivid memories of Peretz’s apartment was the author and theater critic A. Mukdoni.

In his short memoir, “How I. L. Peretz Wrote His Folk Tales,” translated from the Yiddish by Moshe Spiegel, Mukdoni describes his impression of Dinezon’s relationship with Peretz:

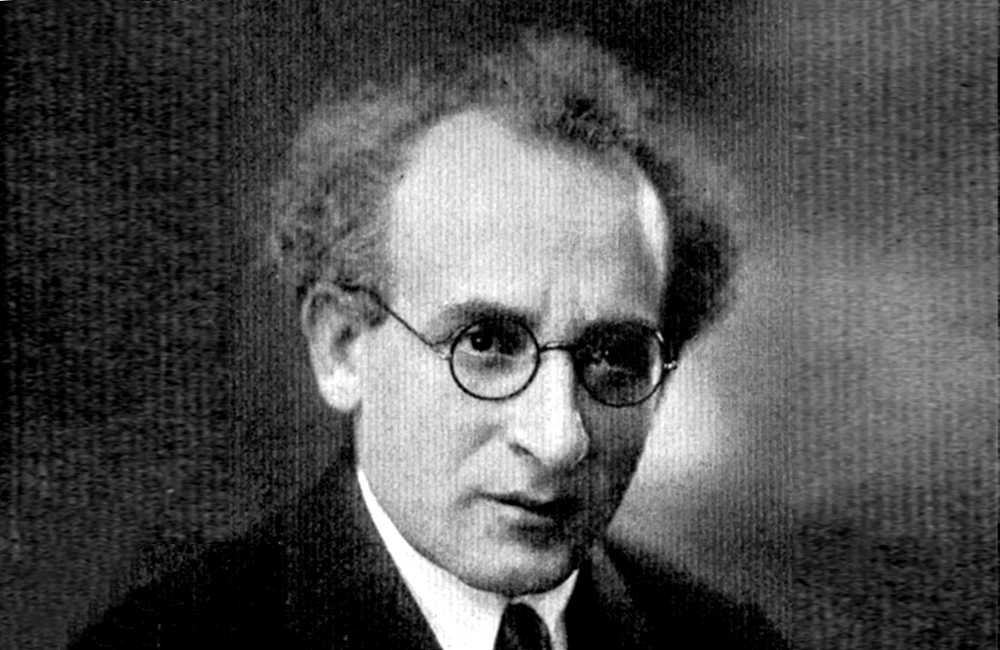

I found Mukdoni’s criticism startling and began wondering about this Yiddish author whose name I had never heard before. Curiosity piqued, I began paging through some of the Yiddish literary histories. One of the most significant early studies of Dinezon’s literary contributions in the mid- to late-1800s appears in The History of Yiddish Literature in the Nineteenth Century by Harvard professor Leo Wiener. Published in 1899, this astonishing book is considered the first scholarly introduction to Yiddish literature for the English reader.

Wiener was born in Russia in 1862 and emigrated to the United States at the age of twenty. By 1896, he was teaching Slavic languages at Harvard University, and just two years later, he was on his way back to the Russian Empire to gather data, “both literary and biographical,” on the history of what he called “Judeo-German (Yiddish) literature.”

What makes Wiener’s research so fascinating is that it’s based on actual interviews with many of the leading Jewish writers of that period. In Warsaw, Wiener spoke to I. L. Peretz, Jacob Dinezon, Mordecai Spector and his wife Beyle Friedberg (who wrote under the pen name “Isabella”), Simon Frug, David Frishman, and many others. In Kiev, he spoke with Sholem Aleichem, and in Odessa, with Sholem Abramovitsh (Mendele Mocher Sforim). Wiener also includes samples both in English and transliterated Yiddish from many of these writers’ stories and novels.

Writing about Dinezon, Wiener tells us:

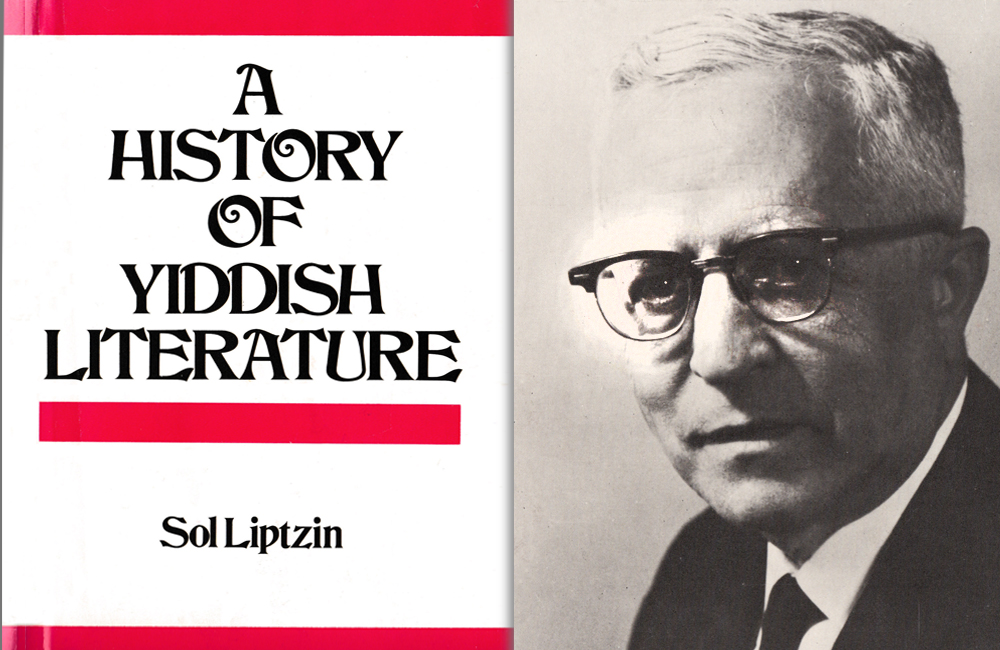

Another entry about Dinezon’s success as a novelist appeared in Sol Liptzin’s A History of Yiddish Literature:

As I continued to investigate, I discovered that Dinezon’s relationship with Peretz began in the late 1880s and was cemented in 1890 when Dinezon, at his own expense, published Peretz’s first book of short stories. Once the books were printed, Dinezon shipped them to Peretz to help him further his literary career.

Dinezon also had an enduring friendship with Sholem Aleichem, which began in 1888 when Sholem Aleichem and his wife Olga paid a visit to Jacob Dinezon’s small apartment in Warsaw.

Sholem Aleichem was on the verge of publishing a literary anthology in Yiddish, and he came to seek Dinezon’s business advice and acquire a story for the first volume—which Dinezon provided, a tale called “Go Eat Kreplach.” Although there were some ups and downs in their relationship along the way, the two authors remained life-long friends.

Clearly, Jacob Dinezon was a significant figure in the last quarter of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th. He was a successful novelist credited with writing the first bestselling novel in Yiddish, a friend and mentor to many of the most important Jewish writers of his day, and a central figure in Warsaw’s Jewish literary community.

This was certainly someone worth knowing about. So I started looking for English translations of Jacob Dinezon’s works, but as hard as I tried, I couldn’t find any. Although I didn’t know it then, that’s when my extraordinary adventure with this once-famous and beloved Yiddish writer first began.