Haynt (Today)

Sunday, August 31, 1919

Warsaw, Poland

Translated from the Yiddish by

Tina Lunson

Edited by Mindy Liberman

[This issue of Haynt is available online at Historical Jewish Press.]

Memorial Tributes

With deepest sorrow, we announce to all family members and friends that on Friday the 29th of August, 3 Elul, at 5:20 in the afternoon, after suffering for a short and difficult time, the death of our very beloved and unforgettable brother and uncle Jacob Dinezon whose soul is in Paradise. The funeral will take place today at one o’clock in the afternoon from his residence at Karmelica 29. —The mourners, his Sister and Family

JACOB DINEZON. We call upon all school organizations to take part in the funeral which will take place today at one in the afternoon. —Board of the United Folks-shuln and Children’s Homes

Together with the entire Jewish people, we mourn the death of our kind folk-writer and singular molder of the Jewish child’s spirit. JACOB DINEZON, of blessed memory. —The Cultural Committee of the Central Artisans’ Union, Leszno 42

With the deepest sadness, we announce the death of our friend and Honorary Chairman, the beloved and very dear popular writer whose soul is in paradise JACOB DINEZON. The funeral will be today, Sunday, at one from the deceased’s residence Karmelica 29. —The administration of the Jewish Literary and Journalistic Society in Warsaw

With great grief and sorrow, we announce the death of the honorable JACOB DINEZON whose soul is in paradise.

Together with the family, I mourn the death of my beloved old friend JACOB DINEZON. —Sh. Abramzon

We sorely mourn the death of one of the pillars of Yiddish literature and the Yiddish “Folks-shuln” and also our close friend JACOB DINEZON. —The Children and Teachers of the Folks-shuln of the Jewish School and Folks-education Society of Warsaw

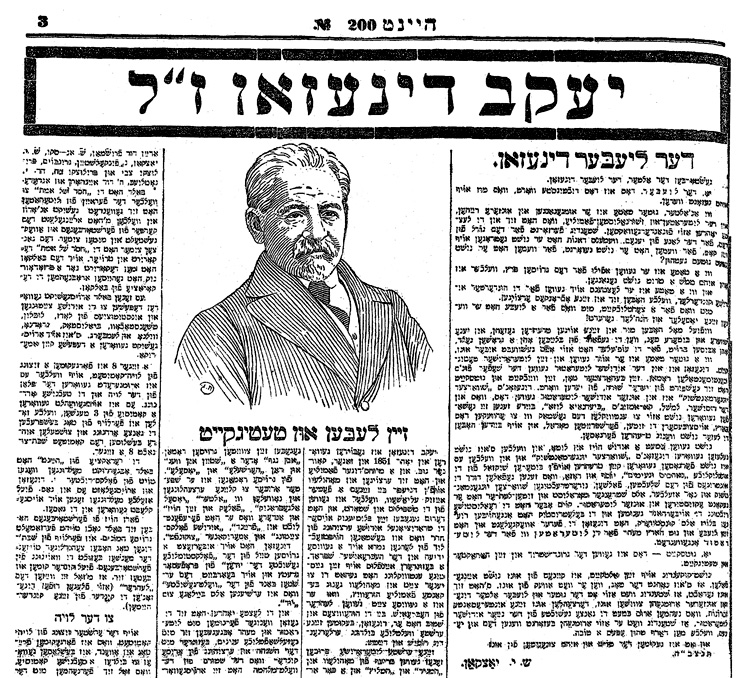

Jacob Dinezon, Of Blessed Memory

Beloved Dinezon

The old, beloved Dinezon has died.

Beloved. Yes, that is the correct word to use for him.

He was spoken of as an elderly, good-hearted father among the family of literati and journalists that has grown so much in recent years.

He was always concerned about the fate and the situation of those whose trouble he had taken on to his own head, who he cared about—and who did he not care about, who did he not do good for?

He was even like a father to the great Peretz, who literally did not make a step without him.

And he was like a father to the hundreds of Jewish children who were taught in his orphanage schools. He spoke of all his little Yoseles and Khaneles with such affection and love!

How many times did we see tears in his eyes during those days when we faced the prospect of being left without a groshen, without a bit of food, for so many infants?

He was like a good father in his literary activities, too. Dinezon was the creator of the sentimental novel in Yiddish literature. His valiant tone, his tenderness and goodness can be felt in every line, in every word. His Shvartser yungermantshik (The Dark Young Man)was to Yiddish literature what Karamzin’s Bednaia Liza (Poor Liza) was to Russian literature. Both were created not so much to develop the taste of the reader as to awaken the heart, improve the principles, spread morality. And readers shed many tears over both of them.

There was hardly a Jewish home in Lithuania where Dinezon’s Shvartser yungermantshik was not read and tears not spilled over the bitter fate of the unfortunate “goodly and pleasant” Yosef and Roza who were brought down by the intrigues of the wicked, false, underhanded dark young man. Like many others who exist in our literature, he was a strict moralist and teacher of principles. But when the realistic direction got the upper hand and the belletristic began to be the only art form, Dinezon laid his pen aside and turned more to the writers than to the written.

Goodness—that was the essence of his character and his works.

Despite his age, none of us wanted to think the day would come when he would leave us. It seemed that our beloved old Dinezon would always be there among us, telling us his fascinating memories that encompassed almost the entire history of our modern Yiddish literature and that he would always take care of it and anyone else who seemed to need a favor.

But now the day has come, and he has been taken from us. —Sh. Y. Yatskan

By Jacob Dinezon’s Deathbed

So that the literary critic and literary historian may be very clear about how this came about—and so that the fact may be firmly established that with Jacob Dinezon, there departs from us a central figure in Yiddish literature, a central figure in our society, and that we all mourn him as such.

We are all aware that Jacob Dinezon takes into the grave along with himself a part of the greatest Yiddish writers like I. L. Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, and many, many others; we know that along with Jacob Dinezon, the custodian, the guardian, the one who worried about Yiddish literature and writers also died.

Jacob Dinezon was one of the key builders of modern Yiddish/Jewish literature. He built it directly with his own artistic talent and then indirectly helped build it even more through his love for it and for its writers. More than the cause, he was the effect. He was artist and servant, creator and supporter, and if we ever saw that he consciously neglected one for another, we can see even in that that it was out of love for Yiddish literature and those who bore it.

Beginning with Avrom Ber Gotlober and Goldfaden, through Y.L. Peretz, to whom he was equal/close, and Sholem Aleichem, to Sholem Ash, Avrom Reyzen, and the youngest Yiddish talents—they all, to a greater or lesser degree, owe thanks for their rise and continuing fruitful work to Jacob Dinezon’s love for the printed Yiddish word and to his talented representatives. He was their caretaker and guardian; he took on their worries as his own, although his worries were not necessarily theirs because he did not want to burden them. He protected them, looked after them, like one protects a nice plant so that it will not be badly affected in its growth and can develop as it should.

It can be said without exaggeration that without the tender care of Jacob Dinezon, I. L. Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, Sholem Ash, Avrom Reyzen, and a long line of older and younger Yiddish artists, would not have become what they did become. Their gratitude to him is the gratitude of all of us.

He himself did not write for several long years; he was too occupied with making it possible for others to write. Everyone was aware of it, and, therefore, trust in him was unlimited. It was through Dinezon that American Jews learned about the situation of Polish Jewry during the war years.

There is also not a trace of exaggeration, not a drop of overstatement when we say that writers here and on the other side of the ocean are left orphans at the grave of the good and beloved Jacob Dinezon.

Also standing orphaned at his grave are the hundreds upon hundreds of Jewish children from Dinezon’s children’s homes that he established in the years after the great storm, and with such love and such craftsmanship. His concerns for those children were among the last words that he spoke.

Love and tenderness: those were the mainstays of his literary and social-philanthropic work, love and tenderness for everyone and everything that is Jewish and of the plain people. And so we all stand here, Jewish writers, journalists, members of political and social groupings, without reference to leanings and parties—all, all standing today shattered over the fresh grave of our beloved Jacob Dinezon. —A. Goldberg

His Life and Work

Jacob Dinezon was born in 1851 in Zhager, Kovne gubernia, into a prominent family. He was educated in Mohilev on the Dnieper by an uncle, Ayzik Eliashev, who was a maskil in that town. He gave his nephew, besides the traditional Jewish education in kheyder—which consisted mostly of Talmud study—information about the Hebrew language itself. Of particular influence on his intellectual development was the Horowitz family, then very prominent in Mohilev, where he was a Hebrew teacher for a period of time. It was there that Dinezon got his first secular education, learning the Russian and German languages.

His first literary efforts were letters from Mohilev in Hamagid and Hamelitz and a few articles in Smolenskin’s Ha-Shahar. Experiencing a strong desire to enlighten the masses who did not understand Hebrew, he began to write in Yiddish, at first popular science subjects such as “Thunder and Lightning,” “Rain and Snow,” and others. Later, he moved over to literature and wrote the novel Der shvartser yungermantshik (The Dark Young Man), 1877, which had great success. In a very short time, it approached more than ten thousand copies. After an interval of 13 years, he released his second large novel, Even negef, oder, a shteyn in veg (i>Stumbling Block, or, A Stone in the Road). And then Hershele and Yosele. From large novels, he later moved to small stories and novellas like Alter, Yosl Algebrenik, Falik and His House, and others that he published in Fraynd, Yidishe Folks Tsaytung, and the American Tsukunft.

In addition, Dinezon translated a large portion of the Popular History of the Jews by Professor Graetz and also revised the first volume of the History of the World that appeared as a supplement to Yud. [See details on Dinezon’s other writings here.]

In his later years, Dinezon was less involved in literature and more interested in social issues, particularly with children whom the storm of the world war had thrown out onto the streets. Dinezon was one of the first who, in the dark days of the expulsions when the streets of Warsaw were flooded with the homeless, began to rescue the children, establishing foster homes and schools to which he devoted himself heart and soul. To the hundreds of children who were educated in his foster homes, he was literally a father. And so his name was, in recent years, ever more well-known and beloved among the widest spectrum of the Jewish population.

His Last Days

As soon as he lay down in bed the previous Sunday, it was clear that his condition was perilous. He himself even felt that his days must be numbered and was concerned about getting his affairs in order. He expressed his wish to be buried beside Peretz and under one gravestone. He assured everyone that he and Peretz had spoken about it and had agreed and paid for a large plot for which he had the receipt.

It is notable that during the last few hours he was conscious, he spoke only of Peretz.

He was also worried about his two nieces, to whom he had been like a tender father, always concerned with their needs and their fate.

Not considering the fact that he knew how serious his condition was, he made jokes.

The Last Minutes

Until one-thirty, he was fully conscious. The pain had eased, and he said with a smile, “Now I am free as a king.” He even recognized everyone around him and called them to him. That situation did not last long; his energy faded, and the patient stopped moving freely. His condition got worse from minute to minute. At three o’clock, the patient was lying restfully in one place, and by his difficult breathing, it was clear that the last moments were coming. The friends and admirers who had come to visit did not leave but stayed by his bed. That situation lasted until fifteen after five when the patient gave a slight shudder and stopped breathing. His eyes closed, and his face, which had had an expression of pain, softened and became peaceful. Five minutes later Dinezon exhaled his last breath. His face was relaxed, his eyes were closed, and his mouth was lightly closed.

Around the bed of the deceased were, besides the closest family, were Dovid Frishman, Sh. An-ski, Dr. Levin, A. L. Shalkovitsh, N. Finkelshteyn, A. Katsizne, and other literati and journalists.

The Funeral Committee

Soon a meeting was held in the Literary and Journalistic Society, including the writers named above, to form a funeral committee. Besides the entire administration of the Literary and Journalistic Society, representatives of various organizations and unions took part. Also Dovid Frishman, Sh An-ski, Sh. Y. Yatskan, N. Finkelshteyn, Grinboym, Tsvi Prilutski and Noyakh Prilutski, Dr. Y. Gotlieb, Dovid Aynhorn, and others.

Soon the khesed shel emes [“kindness of truth”; funeral preparers] that the Society had turned to sent a coffin and laid the body of the deceased in it and set it in the middle of the room. They decorated the whole room with the trappings of mourning and also put them on the balcony . . .

Dispatches were sent to the Jewish newspapers and institutions in Lodz, Lublin, Chenstakhov, Bialystok, Grodno, Vilne, and Lemberg, as well as a dispatch to America.

At eight o’clock the funeral committee held a meeting at which plans for the funeral were discussed. A sub-committee was assigned to talk over the arrangements for one day and to meet again with the rest of the committee for a final decision at eight o’clock in the evening after Shabbes.

The editor of the Haynt had announcements printed about the death of the populist writer and put them out on the street. Many of the announcements were also posted in the streets.

A huge crowd of people gathered outside the house of the deceased soon after the death became known. During the day thousands of people visited the house. Many children came and asked if they could be shown the house where “the teacher” had lived.

The Funeral

At the first meeting of the funeral committee held on Friday evening, it had been decided to create a technical committee to organize the order of the funeral. In that committee were N. Finkelshteyn, A. Gavze, and M. Freyd, who were to coordinate the representatives who would participate in the funeral.

Even during Shabbes, they had notified the following institutions and unions:

1) Folks-shuln and Childrens’ Homes of the former “Arb. Heym” (Workers Home)

2) Evening class at the former “Arb. Heym” (Workers Home)

3) Folks-shul of Sh. Gilunski

4) Artists’ unions

5) Dinezon’s children’s homes

[Included in the list are over thirty-five organizations that include schools, business groups, unions, and publications.]