In the second half of the 19th century, many Jewish writers turned to Yiddish in an effort to reach a larger audience.

At the time, in addition to the language of the country they lived, most Ashkenazi Jews had two additional languages: Hebrew and Yiddish.

Hebrew was the loshen-kodesh (the holy language), the language of religious books, the synagogue, the scholar, and the enlightened intellectual. Yiddish, on the other hand, was the mame-loshen (the mother tongue), the language of the home, the street, the marketplace, and the less educated common people.

In fact, Yiddish, which simply means Jewish, was called “der zhargon” (the jargon), by those who referred to it, and was rejected by many in the Enlightenment movement who favored Hebrew for literary activities. Some biographers suggest that Jacob Dinezon was so discouraged by criticism from the Hebrew Enlightenment press following the publication of his Yiddish best-selling 1877 novel, Der shvartzer yungermantshik (The Dark Young Man), that he refused to publish anything for the next ten years.

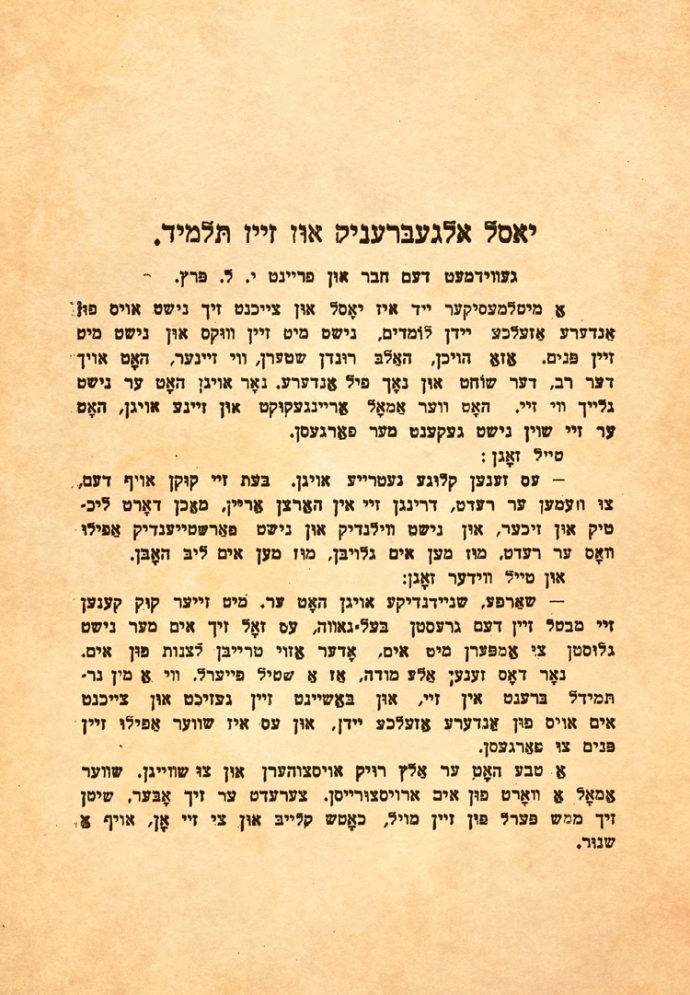

Yet, Dinezon remained an outspoken advocate for Yiddish as a literary language, and actually published I. L. Peretz’s first book of Yiddish stories, Bekante bilder (Familiar Pictures), in 1890. Dinezon provided the following introduction to the slim volume which is here translated into English by Tina Lunson:

The goal of this publication is to give the reading public inexpensive narratives from our Jewish life in our Jewish language, so that each may be able to buy, read, and understand them.

We begin with the novels and sketches of our colleague Mr. I. L. Peretz. . . . Mr. Peretz writes not to flatter the coarse taste of the lower class of reader; rather, he wants to refine and improve him. So we are not being excessive in inviting the honorable readers—who are not yet accustomed to it—to enter into a small Jewish booklet to find something good inside.

They should give us their trust. And not only for the business alone do we advise them to buy the book. We mean that they should read these inexpensive stories with intent, pay attention to the words, and apply heart and mind to the entire content! If they will heed us, they will certainly soon perceive and recognize for themselves our true goal with the “groshen bibliotek” (the “penny library”).

When we can see that we have a public that understands and buys our things, we will with God’s help, not lay down the pens from our hands and will make our poor zhargon literature richer with hundreds of similar stories which will cost less in any case and will bring more use than the most interesting novels which have until now poured out like rain and made a lot of mud.

We hope that you will give our publication a good recommendation and that the words expressed here will not be in vain.