Yudishe folks tsaytung

(Jewish People’s Newspaper)

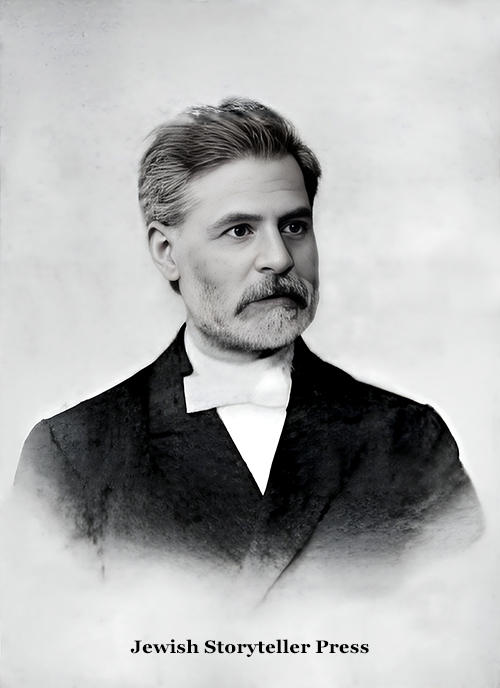

“Jacob Dinezon (On His 25th Jubilee Year)”

By Dr. K. D. Hurvitz

Translated from the Yiddish

by Mindy Liberman

December 3, 1902, pp. 6–7

Twenty-five years have now passed since Dinezon made his debut in Yiddish literature with his well-known novel Ha-ne’ehavim veha-ne’imim, oder, Der shvartser yungermantshik (The Beloved and Pleasing, or, The Dark Young Man). Among that group of Yiddish writers in the [18]70s, who created and produced the new zhargon literature, Dinezon occupies a very exalted position. Without a doubt, he belongs to the talented, who with their works, greatly helped that literature raise itself to the high level in which it now finds itself.

And yet we can hardly find a writer in the literature of today who can really compare with Jacob Dinezon. It is as if he has a talent of his own which is active in a special little world, far from and in a different way than all his other literary colleagues and friends.

Dinezon’s name is very well known to the Yiddish reading public, but in a completely different way from the other well-known and beloved names of our world of writers. Mendele Moykher-Sforim, Sholem Aleichem, Peretz, and others—these are names that are highly valued by everyone, even those who haven’t read them at all or, at the very least, read very little. With Dinezon, it’s altogether different. Dinezon’s works are very widely read, but the majority of Dinezon’s readers belong to the simple folk, namely those who, above all, don’t know what it means to judge an author and evaluate his work. Among such people, you can also find those who have read with excitement and wonder or reread several times this or that work of Dinezon’s and, to this day, do not know who wrote it. And the Jewish public reads its Dinezon very eagerly, reads him seriously, without any tricks, without “evaluations,” because Dinezon’s work awakens in every simple reader the best and most noble feelings. He has brought light and comfort to the dark and troubled Jewish heart. Dinezon writes above all for the people, and he has, in effect, become a folk writer, actually perhaps the only Yiddish folk writer.

Dinezon is a folk writer in an old-fashioned and, I want to say, better sense of the word. He is not a writer who stands above his people and raises his people to grand remote concepts and outlooks that can only be seen from above. He himself is a child of the Jewish people who lives and works among the people, thinks and feels with and like his people, speaks and writes to and for his people, and writes simply from a full heart without specific intentions and unnecessary concepts. He feels the same as every one of the people. Only as with every artist, his feelings are nobler, deeper—thanks to the special strength of his talent. Dinezon’s works, therefore, have not introduced any new ideas or any “new words” or desires into Jewish life. They have not called for any visible agitation among the masses or the youth, and, therefore, his works have always had an enormous and good influence on the people. And it’s easy to understand why his writings present these feelings, thoughts, and hopes, which still live on in the soul of the folk when it’s also dark, and which need, moreover, the paintbrush of the artist to portray it as better, more precise, and more beautiful, and also to become more comprehensible and stronger in all of the people.

Dinezon’s first work in zhargon—Ha-ne’ehavim veha-ne’imim—was written back in the period of the Romantic Enlightenment (1877). Dinezon was still very young at the time, barely eighteen years old. The war between the maskilim and the Jewish people, or, as the maskilim themselves used to say, with the Jewish fanatics, was then in full swing. Therefore, it was no wonder that the young Dinezon, enthusiastic about education and humanity, with all the strength of his young and honest pen, threw himself into the battle with the then so-hated and little-understood Hasidim. However, already in this novel, Dinezon understood the war between the Enlightenment and the old Jewish way of life much more deeply and truly than the other writers of that time, especially the Hebrew-language authors. For Dinezon, those people who fought against education with cruelty and great malice, like the famous Dark Young Man and his Hasidic friends, were not the Jewish people, but just the individual scoundrels; corrupt people who were as far from Jewish ethics and goodness as they were from all the Jewish people. And further, in the novel, Dinezon portrays genuine Jewish characters that enchant us with their good Jewish hearts, like the Friedman family. However, he also knows too deeply and accurately describes the dark individuals of the people, as for example, the God-fearing woman Dvoyre Basye the tavern keeper, and the community member Aunt Shterne Gute, so that meeting such opponents of education and enlightenment we can’t feel hatred or bitter enmity towards them. On the contrary, a deep sympathy results because the opponents, in their darkness and ignorance, are much more unfortunate than the “educated” with whom they wrestle.

December 10, 1902. pp. 2–3

In his first novel, the young Dinezon appears as an Enlightenment-Romantic: the life of the maskilim occurs as a kind of enchanted world with no notion of ordinary mortals, especially the maskilim themselves. Doctors—a Jewish doctor was the ideal of the Jewish writers of that time—were also, in Dinezon’s eyes, true angels from heaven. Thus, Dinezon’s romanticism did not prevent him from seeing all of life with a clear and truthful eye and giving us—already in his first immature novel—authentic, real, and true-to-life scenes and characters. In this, we also see the genuine Jewish character of Dinezon’s art. Every Jew is by nature a romantic: with his strong but distressed soul, he aspires to happiness and freedom. And that joyful, free world sweeps the darkness from his half-closed eyes. But although the Jew is a romantic, a person of imagination, he has never lost his clear understanding, his practical sense, and he has always remained a realist. That means a person who knows real life very well and takes into account all the forces that have an effect on it.

Dinezon, too, is at the same time a romantic and a realist. This explains the great effect his first novel had at the time. Dinezon knew not only to describe for his Jewish readers a more beautiful and better world, a world of education and true, noble, and exalted love. He also knew to portray real life faithfully and accurately. Reality and dreams combine in his work for a beautiful and informed picture that makes the greatest impression on the ordinary reader. Already in his first novel, Dinezon gave up the customary style of the novel that concludes every story with “all’s well that ends well.” Like a realist and someone who is acquainted with life, he knew that the bad often overcomes the good and remains supreme. He ends his novel so tragically that for a long time, many readers, especially women, could not forgive the young and well-loved author.

Dinezon’s works do not invoke anger or hatred towards certain classes of people; he does not call for a war against evildoers. From the start, he described only the suffering and troubles of his good heroes and awoke in the reader the noblest Jewish feeling of pity. Perhaps no Yiddish novel has evoked so many tears from readers, both male and female, as Dinezon’s Ha-ne’ehavim veha-ne’imim (The Beloved and Pleasing), but these were quiet and soothing tears. The reader cries himself out and feels better, and when he remembers the novel, his thoughts float toward the cemetery where lie the innocent dead heroes. His thoughts turn away from the city and real life, where the somewhat black young men rule over and oppress everyone.

And Dinezon does not do this deliberately but simply because Dinezon is, through and through, a Jewish artist fashioned from Jewish morality. He sees everywhere not good and bad people but good and bad deeds in which it is understood that often the oppressors are no more than unlucky and foolish people. This forgiving character of Dinezon’s genuine Jewish art has meant that Dinezon is little read by those so-called Jewish intellectuals who are actually so enthusiastic about strength and war and no more because deep in their hearts, they feel weak, sick, and broken.

Dinezon, as a genuine Jewish writer, sees life as a system of unknown, blind forces that always find themselves in conflict, although they themselves don’t know why. Therefore, the heroes of good and bad lose their value in his eyes. In all his later works, Dinezon describes for us no specific heroes or horrible people who, with a clear intention, wish to bring good or evil to the world. He describes uncomprehending, ignorant people who are often not evil, although they perform evil. He brings us not great and good heroes but victims, often weak, innocent victims of life, who are too fragile to adjust to the difficult conditions of the real world.

Rukhele and her good father, in the novel Even negef, oder a shtein in veg (Stumbling Block, or, A Stone in the Road) are not heroes, but rather, good simple people, who are unlucky in life without rhyme or reason. Khayele, too, with all her faults, is not essentially a cruel woman or a hard person and truly loves her husband and little children. Even Reb Pinchas and the rebbe from whom the entire misfortune befall Rukhele and her mother—even they are not truly evil people whose intentions are different from other people. On the contrary, the rebbe and his court certainly have in mind something beautiful and distinguished. Every reader feels that the rebbe has a definite right to his existence, even though, with respect to Rukhele, he is the source of misfortune and evil. Even more innocent is the poor schoolteacher Simon who causes so many troubles for Rukhele with his own hands even though he loves and respects her almost like his own daughter. But in this lies life’s wretchedness: that petty, selfish interests—perhaps correct on their own—unite in such a way that the good is in jeopardy and cannot survive. The cause of misfortune does not lie with this or that person but rather in the conditions of life and the entire structure of society—this is the deeper, unjust thought we acquire while reading Dinezon’s work. In the higher, ethical view of life, the Jewish artist struggles to figure out the opponent and enemy because he, as a Jew, has never had the strength and courage to hate. Only one consolation remains for him—the tragic truthfulness of life that awakens in us bitter feelings and yet calms the human soul.

December 24, 1902, pp. 7–8

Love and romance were something of a novelty in Jewish life, and one can say, even something “foreign” for Jews. Where the first Jewish novelists described “love,” it was, for the most part, taken from foreign lives, from foreign European gardens. Dinezon even made the effort to Judaize European love and, as much as possible, give it a Jewish character and form. However, it still remains not entirely Jewish in Dinezon’s first works, and even in this true Jewish folk writer, you feel the influence of other literatures. In the enthusiasm for romantic love, it seems that the love must be only natural and simple. We always find something unnatural, un-Jewish, and therefore incorrect about it.

Therefore, we see that in Dinezon’s later work, “love” no longer occupies the primary position in his creations. The writer knows how to find deeper tragic sides in Jewish life. He often knows how to describe authentic Jewish tragedy with the greatest simplicity and naturalness. So he describes for us in his novel Hershele the tragic fate of true Jewish talents who are oppressed and defeated in the poverty-stricken and dark Jewish life. The true and sad figure of Hershele, the truly talented actor who finds no application for his great art and remains unlucky all of his life—shows us how Jewish life is so rich in tragic moments. Only the clear eye of an artist can uncover this.

In his story Yosele, Dinezon touches upon the “social war,” the old war between poor and rich. In no work has Dinezon thought about human actions so deeply and psychologically as in his Yosele. Nowhere does he express as clearly the thought that a person’s will has so little value, either for good or evil. The unfortunate orphan is, in truth, not surrounded by bad people. However, only after Yosele becomes ill do many good people appear who take an interest and have pity on the unfortunate fellow. And these good people were living earlier as well but were not disturbed that Yosele was an unfortunate child and, through no fault of his own, departed this world during the best years of his life. That’s how life is: blind life that knows nothing of reckoning or pity . . . In this work, so full of talent, you feel a strong protest against not only the mighty and wealthy but against all of life with its blind and dark forces—this is a true Jewish protest of Jewish morality against violence and power.

Dinezon’s stories do not evoke heroic deeds, wars, or struggles, but they do not remain without an effect on practical life and often lead to good Jewish actions. I myself was a witness to such a scene: A storekeeper, a boss, sat in his store and was occupied dealing with customers. A little boy in tatters with a pale face came in and begged. The storekeeper asked him to wait and, when he had a little time, gave the little boy a nice donation. He engaged him in a long conversation about where he was from and why he was so wretched. He promised to take care of him and to entrust him to a craftsman.

“Hold on,” said his wife when she found out about the situation. “Maybe he’s just a thief?”

“Or maybe he’s a Yosele?” the storekeeper quietly reproached her, and his wife remained silent. She understood that she was being unjust.

Dinezon properly belongs among the dual writers. That is, among those Jewish writers who write in two languages: zhargon and Hebrew. Dinezon even began writing in Hebrew before zhargon. Smolenskin was the first to recognize the young talent. Through letters, he encouraged him to devote his strengths to the Hebrew language. Dinezon also worked with him on Ha-Shahar. Several very successful articles appeared there, such as “Habit and Control,” “The Story That Was,” and others. However, Dinezon soon saw that the simple Jewish people did not read or understand Hebrew, and since this didn’t hurt him, he abandoned the Hebrew language and devoted himself completely to the Jewish folk language—zhargon. Dinezon loves the Hebrew language to this day. He values it as the national Jewish language that has given us the pure Jewish Bible-culture and the great prophets. However, he writes in zhargon because he writes only for his people, and his people understand no other language. Zhargon is not dear to Dinezon because he writes in that language, but he considers it an insult to the Jewish people when someone insults our mother tongue, which lives until today among the people and has assimilated the great Jewish anguish, the great Jewish tragedy of the Exile.

In addition to his long stories, Dinezon has written many shorter stories and pamphlets in Spector’s Hoyz-fraynd and Sholem Aleichem’s Folks-bibliotek, in Peretz’s Bibliotek, in Yud, and in Yudisher folks-tsaytung.

Dinezon also worked as a journalist and contributed a number of excellent articles. Also, his World History in zhargon, written in the spirit of the Jewish people, is in a form that is easier to comprehend by the simple Jewish reader.

We wish the writer celebrating his jubilee a long, long career working in Yiddish literature for the benefit of our people.