Ilustrirte Velt (Illustrated World)

Thursday, September 11, 1919

Warsaw, Poland, No. 10, Pages 149–151

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Translated from the Yiddish by

Mindy Liberman

(Special thanks to Dr. Agnieszka Żółkiewska

of the Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw,

and the Central Jewish Library, Poland)

(Continued from Part I)

Jacob Dinezon and Yiddish

By A. L. Shalkovich (Ben-Avigdor)

Dinezon was not a “Yiddishist” in the proper sense. In spite of the fact that he wrote in Yiddish for most of his life, he was very attached to the Hebrew language and its old and great literature from all generations. He often liked to look at old Hebrew religious books from ancient times and enjoyed reading the artistic creations of new Hebrew literature.

Art is form, and the main thing for artists is form. The artist who creates nationalistically—and art is always national—has to place a certain worth on the strongest expression of the form, the language. The nationalist artist—and the artist can be nothing else—must choose for his work the language that is, in his opinion, the national language of the people, which contains, and will always contain, the treasures of the national spirit.

However, Dinezon was more of a moralist than an artist. His works have more of a didactic than artistic worth. His intention was to teach the reader through his writing, to preach morality, and to show him the right way. For him, the contents and not the form was the main point. Therefore, he didn’t mull over the problem of our languages at all: Which language is the national language, which is the Pantheon language of the national Jewish art treasures? The question hardly held any interest for him.

Beginning his literary activity in Hebrew, like many of his friends, he switched to Yiddish simply to enlighten the Jewish folk-masses in the only language they understood. The moralist considers chiefly the usefulness, the prompt didactic obedience to his words. The more listeners he has, the more he is understood—that is the main consideration. Dinezon became a Yiddish writer for purely utilitarian purposes, not from a nationalist-artistic standpoint.

Being rooted in the old national Hebrew culture (the ongoing battle against fanaticism and superstition notwithstanding), he was imbued, therefore, with Jewish religiosity, Jewish morality, and Jewish traditions. He possessed a natural love for Jewish national-historical and cultural treasures. He was a Torah scholar and sage who knew and valued Jewish learning, and he loved the Land of Israel and the Hebrew language and its literature. He could not adapt to modern “Judaism” and those of our younger writers who tore away completely from the older Yiddish culture.

And leaving behind the purely practical standpoint, he also saw in Yiddish the primary constraint and the surest safeguard against assimilation. Yiddish is the language of the great Jewish masses. In this way, Yiddish creates a Jewish milieu, a Jewish life. One who writes and speaks Yiddish is a loyal son of the people. Someone who lives in a Yiddish atmosphere is tied to the millions of Jewish brothers and sisters. Writing and speaking Yiddish means feeling and thinking Jewish; it means being a Jew.

However, someone who shifts to a foreign language also stops feeling and thinking Jewish, slowly moves over to a foreign world, is slowly torn away from the Jewish people, and finally becomes assimilated and lost to Jewish life.

Therefore, Dinezon was always strongly against foreign education, against schools with a foreign language of instruction. For this reason, he was so angry with the Jewish intelligentsia who spoke in foreign languages, even among the nationalist circles. Quiet, modest, mild, Dinezon became fired up and furious when he would hear the younger generation speak foreign languages in Jewish nationalist homes.

Today we see a large portion of our intelligentsia who are not ashamed to speak and read Yiddish openly among themselves. At Jewish gatherings and readings, we now hear almost no foreign languages. Several decades ago, it was entirely different. Even our nationalist intellectuals did not have the courage to speak Yiddish openly. When I made Dinezon’s acquaintance at Peretz’s home 28 years ago, everyone still spoke Russian or Polish. Even Peretz himself always spoke Polish or Russian then, not to mention Sokolov and his circle, who spoke only Polish. Only Dinezon remained firm and persevered in speaking only Yiddish. And wherever Dinezon circulated—and Dinezon circulated in many Jewish homes—he caused Yiddish to be the language of conversation.

Many times he complained to me that even today, we hear foreign languages among the nationalist intelligentsia, even among Zionists and Folkists. Dinezon, so thoroughly Jewish in feeling and thought, could not grasp how a nationalist Jew could speak to another Jew in a foreign language.

According to Dinezon, the natural standard for a Jew was always: does he speak the language of his millions of brothers and sisters in the language of the people or in a foreign language?

“This is a sickness,” he constantly complained about these foreign-language-speaking Jews. “This is a sickness, a poison, that distresses our national organism, and we must fight it with all of our powers. We must heal this sickness from its foundation. If someone is a Jew, he must speak the language of the people; he must feel and think in the same language in which millions of our Jewish masses feel and think.”

Yiddish was, for Dinezon, the main barometer with which to feel the Jewish pulse, the natural bond with the Jewish people, and all this without any pretentious theories and modern slogans, but through uncompromising love of the people through the natural, elementary bond with the Jewish people to its emotions, thinking, and creativity.

The Beloved Teacher

(Jacob Dinezon and the Children’s Homes)

By M.

Jewish political life has grown up tremendously. All of its energies were dragged into the political uproar. Everything was given and sacrificed to that. The Jewish intelligentsia threw away study and learning; writers offered up literature on the altar of politics. In time, the watchword of the Jewish school became topical. The Jewish public school was talked about at every party conference, every discussion evening.

However, in truth, school was no more than an abstract concept, a political slogan for everyone. Very few attempted to give any thought to the creatures that fill the school, who breathe school air—the children. The children don’t exist for any of the politicians. Everything is thought of on a grand scale, that is to say, without any gray. Children, the school problem—those are the dominant words; rarely does anyone give thought to a child, to school. The child as a person is decried. What is one child worth compared to the great political problems and combinations? Only someone like Dinezon, who was cut off from the political chaos, who stood on the side away from the commotion—only he had the energy to devote himself completely to the Jewish child.

Sympathy and compassion—these are the foundational tones of Dinezon’s work and life. He also developed pity for the abandoned, forlorn Jewish child. He had very little interest in research about the Jewish school system or all the plans for a school network. Every Jewish child who was installed in a school, who was learning and being educated, was for him a win—even more—an occasion.

The schools were in a sorry state, threatened with liquidation. The school association spoke openly about liquidation. Concerned, I approached Dinezon. “It’s bad. We’re closing the schools.”

Trembling he cried: “Don’t say that.” I barely got a word out. “What do you mean? And what will you do with the little children? They’ll starve, God forbid.”

Everyone threw up their hands, losing hope about rebuilding a Jewish school system—he, however, saw before him the starved Jewish child, and nothing could induce him to close their home.

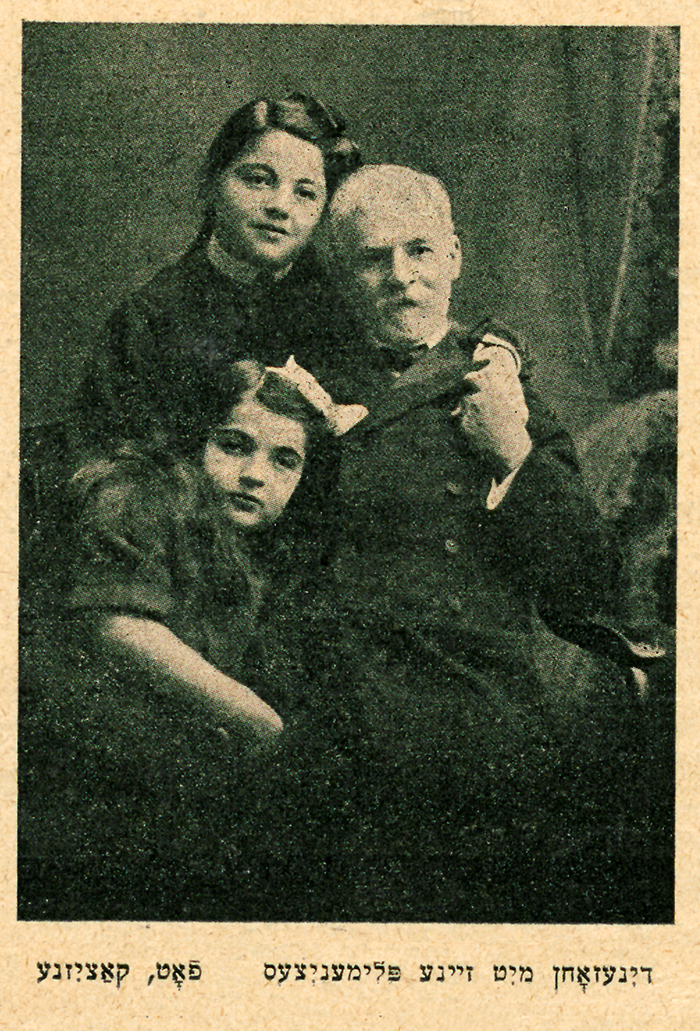

He would speak to the children with a fierce love, conducting conversations about everything in the world. Shabbes afternoon, children from the older classes gathered at his place on Dzielna. He read, chatted, argued with them. The children revealed everything to him; they had no secrets from their elderly friend.

Some of the children wanted to read books. Dinezon himself went to register them at a Jewish library. In addition, he exchanged the books himself so the children wouldn’t read anything unsuitable. God forbid their pure little souls might be stained. Such concern for every single child was moving, even for teachers, who think and feel with every child. One child did not return his book to the library on time. Dinezon himself went to Okopowa Street to take the book, so another child would have something to read in the meantime.

In general, as a Maskil, he believed strongly in the power of knowledge and reading. He would often try to convince the children that all people are truly good; one simply had to know how to live with them.

Receiving American condensed milk for the first time at the schools was an occasion for him. He ran into me on the street that day and, with a radiant face, said: “Do you know what? The little children will have a little something to eat. Some of my children are in a bad way, poor things.”

If a child pleased him, he made the effort to run to school to care for him himself.

He had a magical effect on the children. I remember two facts: We entered a home for beggar children. Dinezon asked them to tell him a story. They told him about a boy who ripped out the tongue of a little bird. Dinezon began to tremble. “Feh!” he cried. “He was a bad boy! It would be better for me to tell you about a smart and good child.” And he told them a little story. As he was leaving, two beggar children ran to him: “Teacher is so good and gentle. If he would remain with us, we’d all be good, fine children.”

The children would visit with the old man for a long time.

He was in a children’s home. I came upstairs—there was something going on—they suspected a boy of stealing. He screamed and cried but would in no way confess. In the middle of this, he spotted Dinezon. He looked at Dinezon for a few minutes and said: “I will tell the teacher everything, the whole truth.”

“Why me exactly?” asked Dinezon. “Because the teacher believes all the children, therefore we believe the teacher too.”

And the last thing: he derived so much pleasure from his summer colony. With wonder, he shared so many stories of clever children with the teachers!

Yes, in truth, the Jewish child whom he loved so passionately has been orphaned.