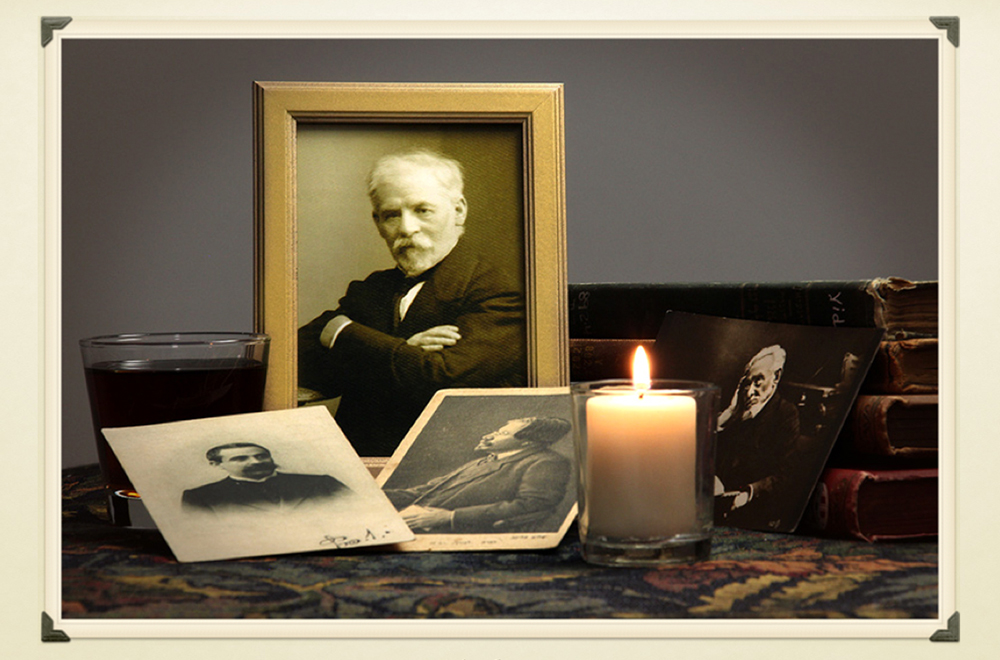

Exactly one year ago today, on September 3rd, 2019, my family and I celebrated the Yiddish writer Jacob Dinezon’s 100th yortsayt for a second time in New York City. Three days earlier, we returned from Poland, where we commemorated Dinezon’s memorial on August 29th, the anniversary of his death on the secular calendar. September 3rd marked the date on the Hebrew calendar.

On Sunday afternoon, September 1st, we had the opportunity to attend one of the final performances of A Fidler Afn Dakh, a Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof. In the early 1960s, the Israeli actor and director, Shraga Friedman, took the words and lyrics of Fiddler and translated them into Yiddish. So imagine hearing the songs we all know so well—“Tradition,” “If I Were A Rich Man,” “Sunrise, Sunset,” and “Anatevka”—performed in the original language in which they were written by the Jewish author Sholem Aleichem in the late-19th and early-20th centuries.

In the 1950s, Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish Tevye stories were translated into English by the playwright and producer Arnold Perl for his production of Tevya and His Daughters. Perl’s work was adapted, enlarged, and transformed by Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock, and Sheldon Harnick into the Broadway musical, Fiddler on the Roof. Shraga Friedman’s A Fidler Afn Dakh brought Sholem Aleichem’s stories full-circle back to Yiddish.

Why? Why would so many writers, actors, and directors work so hard to keep Sholem Aleichem’s stories alive in the world? And why would audiences continue to come out in droves to attend their performances? I can only tell you from my own experience sitting in the theater watching this extraordinary production: Within these stories, with all their joys and sorrows, we are not only reconnected with a lost and nearly forgotten world, we are also reunited with the soul of a people. This is what was missing in Warsaw—the Jewish soul.

Dinezon writes, “It seems that in every place and in all times the Jewish heart is filled with troubles. One just needs to know the right word or the touching melody, and the thick ice that forms around the Jewish heart by cold life breaks open, and tears pour out.” Indeed, tears poured out as we sat in that theater on 42nd Street and remembered . . .

Make no mistake, Jacob Dinezon and his friends Sholem Aleichem and I. L. Peretz were not small-town, shtetl Jews. They were sophisticated, enlightened urbanites. But they still carried the Jewish soul from their childhood days and were able to express it in their writings. That’s why their works are still so important for us today. That’s why we published Dinezon’s novels in English. So that soul of his Yiddish world would not be lost to future generations.

On the evening of September 3rd, I had the honor of presenting a talk at the YIVO Institute, where people gather to keep the Yiddish language and culture alive. What better place to remember Jacob Dinezon and his contributions to Yiddish literature and the Jewish people?

Dinezon, in his writings and his life, was what we call “a mentsh”—a person of the highest integrity. Imagine! All these years later, he is still a role model for us through his writings and good deeds. That’s why it’s so important to remember that 100 years ago—now 101—there was a Jacob Dinezon in the world!