by Nachman Mayzel

From Perets: Lebn un shafn

(Peretz: Life and Creativity)

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Vilna: B. Kletskin, 1931, Pages 161–174

Translated from the Yiddish by

Janie Respitz

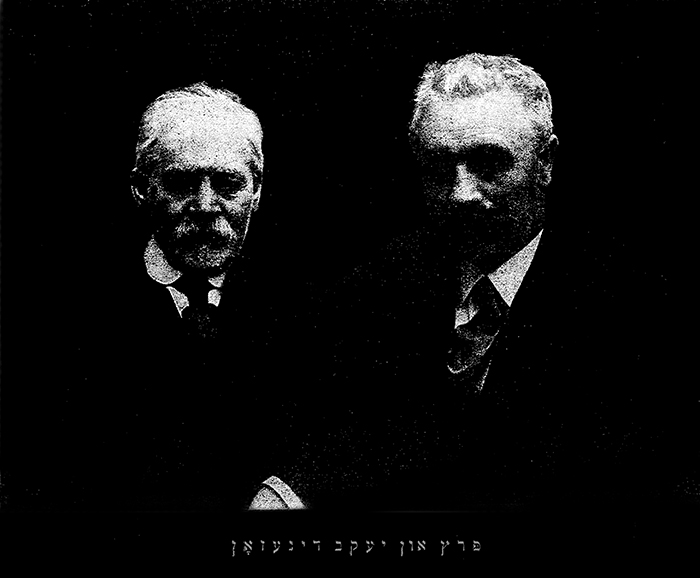

Peretz’s name, his life, and his work are tightly connected to Dinezon’s name. Beginning in 1889, the year Peretz entered Yiddish literature, an acquaintanceship was formed between Peretz and Dinezon. What immediately emerged was a friendship that quickly turned into a wonderfully rare type of brotherhood. This remarkable connection lasted twenty-five years without any interruptions. Dinezon was like Peretz’s shadow, accompanying him everywhere. He participated in all of his joys and worries, helped him in various matters, and was his regular advisor, even concerning intimate affairs. Much has been written about the friendship between these two very different personalities, and efforts have been made to find the key to this Peretz-Dinezon problem.

Because of personal experiences in his youth and a love that was cut off at the very beginning of its blooming, Jacob Dinezon withdrew from his own active personal life and suppressed his desires and passions. If you can’t go over it, you must go under it. This was Dinezon’s philosophy of life, which left a stamp on his entire life. The sensitive Dinezon was also affected by the fact that his works were not properly received by his closest friends, the better Yiddish writers. His self-love was so low that he abandoned literature for many years. However, instead of being bitter and feeling contempt for this inner breakdown and his holding back from writing, his heart became filled with motherly feelings of kindness, and he was ready to devote his life to helping others. In this role of motherhood, he displayed many talents and beautiful qualities. He showed great interest and veneration for many Yiddish writers, however, his entire soul and life were devoted to Peretz. He carried out quiet “love affairs” with many Yiddish writers, but his true, permanent love, which he lived with for tens of years, was for Peretz.

In his heartfelt characterization of Dinezon, which Peretz published in 1904 (Di Yidishe Bibliotek and later republished in Peretz’s Essays and Feuilletons), he wrote about his close friend: “He is an honest, devoted swallow, who is ready, until the last second, to tear out the last feather from his breast to serve as a bed to keep the nest warm . . . and is prepared to tear open his breast and nourish the baby with his own warm blood . . .” And how many times did Dinezon, this “honest swallow,” tear “the last feather from his breast” to make Peretz himself comfortable “and to warm his nest”?

Quite often, Peretz was the impulsive child and did not take into account that the mother, Dinezon, also had desires, passions, and a character. But Dinezon also loved this torture due to the boundless love he possessed for his beloved and favorite child, Peretz. He was so dear to him, even with all his whims and caprices.

The strongest and most striking explanations of the relationship between Peretz and Dinezon are in Peretz’s letters to him, which were protected by Dinezon like a relic. Peretz was not at all a letter writer. “In my nature, I hate writing letters,” he once wrote to Sholem Aleichem. But, he wrote regularly and gladly to Dinezon whenever they were apart. From the 180 letters and notes which we have managed to collect (Peretz’s Letters and Speeches), 89 were written to Dinezon. We must also observe that during most of the years of their close friendship, they were together in Warsaw.

The majority of the letters from Peretz to Dinezon were to the point or were short, friendly letters on postcards. However, from these simple, non-contrived letters, we can gather many details about the character of their relationship.

First of all, we see the simple, thoroughly human Peretz with his intimate, personal worries and interests. They show us Peretz, the calm, intimate Peretz with his encounters with reality, with people, and with nature. In real life, Peretz was largely helpless and always needed Dinezon to help him. In 1902, he replied to a letter in which Dinezon was asking him for advice: “First of all, do not follow my advice if I give it to you; you know, I am not the person who knows how to handle life and consequently hang in space . . .” (Letters and Speeches, p. 65) Without Dinezon he could not sell his published books. He asks him for pity and to return from Kiev as soon as possible “because since you left, I have not sold one book to any book peddlers because I don’t know them and they don’t know me.

“Come to Warsaw and sit with me. As long as the landlord will permit us to remain here, my bread will be your bread, my drink will be yours. Don’t forget I owe you so much. Even if you eat with me for a long time, it will never cover my debt . . .”[1] (p. 73)

Peretz asks Dinezon to suggest to Ha-Melits to promote the publication of his novellas and articles. Peretz’s helplessness goes so far that letters he wrote remained unsent or were lost. “It’s a mystery,” he complained to Dinezon, “how my first letter disappeared. I searched the table for three days and could not find it. I had to write another one.” (p. 83) Another time Peretz wrote: “I answered you promptly. I put the piece of paper which I had written on both sides in an envelope and also attached a stamp . . . but now I cannot remember if I sent it or if it is lost . . .” (p. 65)

Already in the early days of their friendship, Dinezon became Peretz’s representative in dealing with publishers and editors. He sent Peretz’s work to Sholem Aleichem as early as 1889 and carried out negotiations for Peretz. In a letter from Peretz to Sholem Aleichem, we read: “In your short letter, you write you have found good passages and bad passages in my poem, and you would publish it only with the condition that I agree to the conditions you have presented to Dinezon.” (pp. 33-34) In his article, “A Week with Peretz,” Sholem Aleichem wrote: “He, Dinezon, not Peretz, later sent me an entire ‘Tetrad’ of short stories by I. L. Peretz . . . from then on, everything Peretz spewed out went through Dinezon’s hands.” (p. 71). Sholem Aleichem added: “the fact that Dinezon was his business secretary, as you call it (this article was written in America, N.M.), or Finance Minister as we jokingly called him, is understood because in money matters, Peretz, according to Dinezon, was ‘worse than a child, a child who needs his mother, a devoted mother, ready to sacrifice everything for him at every moment.’”

Years later, Peretz was still dependent on Dinezon for everything. In a letter to J. Dinezon from 1910, he asks: “Go to Mr. Ben-Avigdor and calculate an amount for my work. It seems to me he is trying to cheat me, and I don’t know why, and I, as you know like when things are clear.” (Peretz’s Letter, p. 118) This is how Peretz characterized himself and Dinezon: “ . . . you without me are nil, and me without you, even less. I am a minus. When you will finally get here, the nil and minus will amount to something.” (p. 83). Peretz relied so much on Dinezon that he did not want to manage any of his business matters by himself. In 1907, he wrote to Dinezon: “I spoke very little with Miller (a representative of an American Yiddish publishing house, N.M.). I saw he had a long letter from you and realized I did not have to say much.” (p. 135) In his last years, when someone asked Peretz about his credo and biography, he would reply with a few lines and then add: “For biographical material, please write to my colleague J. Dinezon.” (p. 224) Sometimes, however, Peretz would be angry if Dinezon did something without his knowledge or behind his back. On this point, it is interesting to see the angry lines written by Peretz to Sh. Niger explaining why he was sharing his memoirs in Der Yidishe Velt: “ . . . you write about troubles and punishments, both are too distant and incomprehensible, and I knew Dinezon was involved with this. He winked at me. I now understand: He is writing behind my back . . .” (p. 22)

Dinezon’s first impressions after meeting Peretz are very moving. In a letter to Sholem Aleichem, Dinezon wrote: “ . . . recently while I have noticed the entire poor household is so disdainful and has become unworthy, I have found a new friend and writer, and my heart tells me this is a true friendship, true love and respect for the person himself and the talent he possesses. I am speaking about the beloved poet Mr. Peretz. We fell in love with one another with a pure unconditional love. I don’t know what this man sees in me, although it is clear to me every day. He sends me everything that emerges from his blessed pen, and I gain great satisfaction and pleasure reading his works, which are as valuable as gold.” These words, which were written by Dinezon, are quite remarkable. They were written after his first meeting with Peretz in 1889 about their mutual love, which would never go away!

Peretz has been reproached many times for not properly valuing Dinezon and sometimes treating him with disdain. This is not correct. Perhaps in a moment of anger, Peretz would lash out against Dinezon with a harsh word, and perhaps he permitted himself an occasional contemptuous smile. But deep in his heart, he deeply respected Dinezon and knew how to value his affection. In Peretz’s letters to Dinezon, we often see his deep respect and love toward his dear friend. Around 1892, Peretz wrote: “I received your letters. The first one alarmed me greatly, but I wished for a second, and when it arrived, I calmed down. I thank you from the bottom of my heart for your promise to come to me. I must confess I have always carried resentment for you in my heart (this was in the third year of their friendship, N.M.), as you did not believe in my open door and concealed a lot from me. However, those days, the days of secrets, have passed. We are two poor men, and we will help each other as much as possible.” (Peretz’s Letter, p. 81) “Believe me,” Peretz wrote to Dinezon in the same letter, “I will rejoice with you as a groom rejoices with his bride precisely when they connect due to true love and not due to money or lineage.”

When it came to Dinezon, Peretz was sentimental and sensitive. When he received a sad letter from Dinezon, he responded: “I received your letter which is filled with sadness and bitterness. You joked that you wanted me to comfort you. How can I comfort you when my soul is also sad?” (p. 85) And then he wrote in another letter: “My heart has not turned away from you; to the contrary, I have always loved you.” (p. 91).

Peretz respected Dinezon like a father; he often understood his winks and hints and even knew his weaknesses and obeyed. In a letter from Kiev, Dinezon suggested Peretz invite A. Shulman to contribute a piece of writing. Peretz did not want to and wrote to Dinezon: “Can I ask him for an article? . . . I see your face, it is sad; my words will not please you; okay, let it be; as you wish, I will write to him now.” (p. 58) This is how he spoiled Dinezon. He described the surroundings at the spa and wrote: “Why am I writing this to you? Only because you should know I am wandering around like an orphan.” This was in 1911 when Peretz was already sixty years old. He ended this long letter to Dinezon with the words, “this is sad.” Another time, Peretz sent a telegram and did not waste any words. As a result, he received a scolding from Dinezon, and he replied: “For the six superfluous words in the telegram—forgive me.” (p. 164) What is interesting is Dinezon’s short reply to his reproach: “I have no response to your letter. You call me a dreamer, I call you a pessimist. I am sticking to my words: In the right hands, all is done right.” (p. 137)

Particularly fitting and touching is the letter Peretz wrote to Dinezon as a reply to a sad letter about an expropriation that took place in Dinezon’s house when a few things were taken. “I took a bit of pleasure from your robbery,” Peretz wrote. “Thanks to the robbery, you wrote me a nervous letter . . . the wall is looking at you with melancholy and does not allow you to forget the robbery. This is good. You are escaping from life, from everything which makes you nervous and brings out deeper tones. Life has intruded in the form of an expropriation. Here, don’t cry. There was also a bit of danger and you were saved from a knife . . . tell the truth, have you been dreaming about a knife? If yes, describe it in a letter.” This letter ended with the following words: “Be well and strong. Make yourself new clothes. Live your life and don’t wait for someone to knock down your door and break the locks . . .” (pp. 138-140)

Peretz always summoned Dinezon back to literature. “I don’t understand your methods and your actions,” Peretz wrote in 1893. “What happened to you? Can a woman forget her child? And you threw literature away? Write to me and explain what this means.” (p. 86). In another letter (from 1894), Peretz asks Dinezon: “If you don’t send me the stories within the next two weeks, you will kill the rest of the publication. It is enough that the blood of the Yontev Bletlekh (Holiday Pages) rides on your coattails. Do you also want to spill the blood of ‘Literature and Life’? Maybe you can actually write something?” (p. 88-89) In a separate edition, Peretz printed J. Dinezon’s Hershele, which was published in Di Yudishe Bibliotek (The Yiddish Library). “I printed the whole thing,” wrote Peretz, “maybe this will be your chance.” (p. 89)

It is interesting how appreciative Dinezon was that Peretz encouraged and influenced him to return to literature. We learn about this in Dinezon’s letter to Sh. Niger. In a very long letter from Dinezon (from 1911), which had the characteristics of confession and autobiography, Dinezon wrote: “ . . . I couldn’t not write, however, publishing what was already written did not cost me any special effort or spiritual strain. I once again published the long, previously written work, actually at my own expense, right after I befriended Peretz, who persuaded me to do it.” (Tsukunft, New York, 1929, p. 624) These words from Dinezon weaken the false accusation that Peretz repressed Dinezon as a writer. This is what Dinezon wrote to Sh. Niger: “ . . . the following saying is true about me: ‘There were eight guarding the vineyards, but my vineyard was not guarded’—no one could watch over my vineyard except me. However, things that were never difficult for me to do for Peretz or other colleagues, like publishing entire collections of their works, were for me an impossibility. Why this is so, I can’t even explain to myself.” (p. 624)

In another place, in a letter to a close woman friend (see Pinkes, the publication of American YIVO, 1928, Vol. 1, No. 4), Jacob Dinezon tries to characterize himself: “ . . . what should I do, when this is, after all, the truth (that he is a “sensitive man,” N.M.) and I can’t be any different (although I often want to be). This is how God created me. God gave me more heart than brains. My heart always comes before my common sense. I am fighting for self-existence . . . what can I tell you? It is enough that my idealism has led me to a certain level of asceticism. And through this, I have become so lonely and alone and have remained this way until today. Perhaps you do not know this inconsolable fact: I remained unmarried. I do not have and do not know about tenderness and gentleness in my lonely half-ascetic life, which only a devoted wife can provide, and my life would not be as cold and inconsolable as it is.”

They tried many times to show that Dinezon lacked character in comparison to Peretz. This is not totally true. Dinezon was not so submissive in matters concerning Peretz, even in matters which had an absolute connection to Peretz himself. Here we see the emergence of a controversy between Peretz and the editors of Yidishe Velt (The Yiddish World) about his Memoirs, which they published. Peretz was extremely irritated and wrote an angry short letter to Vilna, saying he wanted to cut ties with them completely. (See earlier p. 165). However, Dinezon stepped in and did not overreact to Peretz’s anger. He wrote to Vilna, to the editors of Yidishe Velt: “After re-reading your letter, I wonder why you took Peretz’s momentary anger so seriously. Do not fear. One can say about him that his anger does not last for more than a moment. He soon realizes the other side is also right. I was not present at the time he wrote you his angry postcard or letter and hardly knew anything about it. He told me about it later, and he received a well-deserved scolding from me.” (Tsukunft, p. 629) “Generally,” warned Dinezon in this letter, “in such conflicts, caprices, or simple misunderstandings, which can occur between Peretz and your esteemed editors, you should always inform me immediately, and I will do what I have to do to come to an understanding and agreement. (p. 629) Regarding the present question as to whether or not you should continue with the publication of his memoirs? Of course, publish them! Publish as much as possible, as much as you can. I am taking all the responsibility upon myself. Enough said!”

On the contrary, not only did Peretz take pride in his friend, Dinezon reproached Peretz for behaving so simply. He wrote Peretz a letter from abroad asking him to “examine himself from inside out.” (See Letters and Speeches, p. 179)

A good witness to the Peretz-Dinezon friendship is the sensitive and kind S. An-ski. He was in Warsaw and was close to Peretz and Dinezon. This is what he wrote (See S. An-ski, Collected Works, Vol. X, p. 164): “The closer I got to them, the deeper I felt the intimate friendship between them. Only when they were actually inseparable in my mind and heart was I able to comprehend.

“There is a folk expression about the highest form of friendship and love between two people: ‘One soul in two bodies.’ The opposite could be said about Peretz and Dinezon: ‘Two souls in one body.’ It is hard to imagine two personalities, two individuals, who were so far apart as these two friends, yet they were intimately united and inseparable for many years.

“Peretz, with his sparkling eyes, animated movement, dazzling and shining words, always aroused in me the image of a large, precious, shiny diamond. Like a diamond, this person was pure and bright; like a diamond, he sparkled with every polished edge, like a diamond, he was strong in his opinions. And also, like a diamond, he sharply cut those who stood in the way of him achieving his high goals. Dinezon, with his quiet calmness and his loving glance, beamed with unending tenderness, was always ready to give up everything for someone else. Dinezon, who was organically incapable of saying a harsh word about anyone or causing them the smallest of grief, was in all aspects the opposite of the raging, fiery, strong Peretz, and these two friends were united in one body. (In the Yiddish Velt, 1915, where S. An-ski’s article was first published, there is a blank after a word in the fourth line. It is very likely the censor left out these two words—raging and fiery—which An-ski used to characterize Peretz. N.M.) There was nothing, no literary plan, no accomplishment, no idea from either one that the other did not know. They both lived the same life, had the same interests, the same joys, and the same worries. Dinezon was the host in Peretz’s house, just like Peretz. He knew where every small piece of paper lay and often, without asking, would respond to Peretz’s letters.”

I once asked him, “Peretz, why didn’t you reply to my letter?”

“I assumed Dinezon did,” he replied.

“Their closeness,” wrote An-ski, surpassed all levels of friendship. “Such an intimate connection can only be found in an old couple who has lived together for half a century and, due to love and devotion, have lost the boundaries of the individual.”

The words in a letter written by Dinezon to a close woman friend are interesting. He tells of Peretz’s relationship with his son Lucian: “Peretz,” wrote J. Dinezon, “is a passionate, gentle father and loves his only son very much . . . If Peretz needs to find out something about his only son, he asks me to ask him. I am fortunate he tells me everything and can spend entire days with me.” (Pinkes, publication of YIVO, New York 1929, Vol. 11, No. 1)

We find a few important traits about the Peretz-Dinezon relationship in the memoirs of Roza Lax-Peretz, who for a while observed Peretz and Dinezon (Literarishe Bleter, 1925, No. 42-43): “I had the impression that the friendship was the center and most important thing in Dinezon’s life. Dinezon would always joyfully tell me how he met Peretz . . . He considered his closeness to Peretz as fate predestined by God . . . Dinezon would go to Peretz often, including every Sabbath. Without fail, he would spend the entire Sabbath at Peretz’s. Peretz would always greet him with a happy smile on his face. It was well known that Dinezon’s visits brought him great pleasure. I believe Dinezon had his own key to Peretz’s house. He would enter quietly and immediately begin to talk to Peretz about literary financial matters . . . then he would begin his Sabbath duties in Peretz’s house: he would trim and water the flowers. When he was done, he would spread a newspaper on the table, place a box of rolling paper on it, spread tobacco on the paper, and make cigarettes for Peretz . . .”

Roza Lax-Peretz came to this conclusion about the Peretz-Dinezon relationship: “I can see both of them talking. Dinezon had a serious expression on his face, while Peretz’s appearance was always lighter and carefree. Although they were, I believe, the same height when they spoke, it seemed Dinezon looked up to Peretz. When Dinezon spoke to Peretz, his eyes shone with love, respect, and pride, and besides that, a certain solemnity. Peretz loved Dinezon very much and always needed him, but Dinezon was not everything to him as Peretz was to Dinezon . . .”

Avrom Kin, one of the publishers of the daily Folksshtime in Berdichev, shared a characteristic episode with me. He came to Warsaw in 1912 to invite Peretz to contribute to his newspaper. He was at Peretz’s. He was at Dinezon’s. By that time, Peretz was living on Jerozolimskie Avenue. Dinezon had a key to the elevator as well as to the front door of Peretz’s home. After a discussion about the new newspaper, Peretz said to Dinezon: “Yankl, sell me!” Dinezon determined a price of 50 rubles a month for two articles or novellas. All the while, Peretz moved to the side as he did not want to partake in money matters. Kin took out 50 rubles and put them on the table.

“Take the money away,” Peretz called out. He did not want any payment. Two weeks later, the Folksshtime received the magnificent story “The Apron” from Peretz with a postscript: “This is a gift for no money for the tailor from Berdichev.”

In an article about Peretz, Sh. Niger wrote: “Peretz the speaker in word and writing (the New York Tog, 1930, April 20) moved the Peretz who searched for ears to listen to him. He longed for eyes that would look back at him with thirst and appreciation and delight . . . Perhaps this is how he attracted the masses, and perhaps this was one of the reasons he befriended Dinezon. The masses were always ready to listen as long as you had something to tell them, as long as you said it with strength and confidence. And Dinezon never interrupted when Peretz spoke . . . even when Peretz repeated a story he had already heard. He always gave him his full attention and was filled with joy, as if it was Dinezon’s own accomplishment . . . Dinezon was the audience that Peretz needed when he sat at home. A public audience at a gathering was, in a sense, a collective Dinezon . . .”

Dinezon was among the first to appropriately appreciate Peretz. He was the first to publish Peretz’s Yiddish works in book form and wrote, as early as 1890, a few positive words about Peretz’s creations. We dealt with this earlier. (See pp. 73, 79)

It is interesting how Peretz’s love and closeness for Dinezon rose. At first, he refers to him in his letters as “my friend,” then “my soul mate,” later “beloved Dinezon,” “beloved Yankev,” “beloved Yankl,” as well as “brother.”

They were and remained brothers, devoted, faithful brothers, who were deeply in love.

Peretz’s death shocked Dinezon to the core. He could not find his place and missed him so much until he, too, died and found eternal rest beside Peretz.

Those who are loving and pleasing in life will not be parted by death.

Addendum from 1945 Version [2]

In order to conclude this portrait of “Peretz and Dinezon,” we will provide a few excerpts from letters written by Jacob Dinezon in July 1919 (over four years after Peretz’s death) to Herman Bernshtryn in New York. We see that Dinezon maintained his admiration for Peretz and bore concern for his wife. “This has to do with,” wrote Dinezon, “published dignified condolences, material respect, the situation of his family, especially the widow of our unforgettable and insatiable great colleague Yitskhok Leybush Peretz of blessed memory. As his closest friend in his lifetime, it is my obligation to continue the same friendship and relationship with his sad, lonely remaining family members. It hurts me to tell you how negligibly little has been done until now to honor and perpetuate the memory of the great Peretz in general and, specifically, to provide his widow with a bearable existence. Upon retirement after twenty-five years of tirelessly productive work for the administration of the Warsaw Jewish community, Peretz’s widow receives barely 144 marks as a monthly pension. Of that, they took eleven marks monthly until last month when they settled on a sum of 200 rubles which Peretz owed on a loan he once took from the administration’s fund.”

J. Dinezon was astonished at how one could live off such a negligible amount. And he continued: “You are probably wondering why it has occurred to me to tell you about the great injustice of the Warsaw Jewish communal administration and why I have kept secret the simple criminal ungratefulness of the entire Jewish public in our old Europe, as you call it from over there. I will answer briefly what happened four years ago, right after Peretz died, when I received a response from one of the most important and respected Jewish communal activists from St. Petersburg when I had a conversation with him here in Warsaw about creating a Peretz Fund which would perpetuate his earnings and great name in general and would look after the existence of his bereaved and lonely widow in particular. ‘Peretz,’ this man told me, ‘did something that was not very smart. Could he not find a better time to die? He had to die exactly at the time when the whole world is at war, and all of society’s strengths and energy must be focused on saving the countless hungry, pillaged, and homeless!’”

“Yes, you are correct, my colleague Peretz was really not smart dying so suddenly and unexpectedly. He did not take the time to consider the timing of his death, nor did he look around to see in what city and in which country he died in. So therefore, I have come, his friend who accompanied him everywhere, who unwillingly outlived him, to correct his ‘non-smartness,’ which he displayed by dying at an inappropriate time in an inappropriate city. And so, I turn to you, so you and the rest of our colleagues will fulfill your obligation and exert your influence on our American brothers, for whom the name I. L. Peretz is not unfamiliar, to do something which would seem appropriate for you Americans . . .” (This letter was republished in Yidishe Kultur (Yiddish Culture), No. 809, 1944, pp. 90-91)

As it is known, Jacob Dinezon, after Peretz’s death, continued the sacred work with the Jewish schools and Jewish orphanages which Peretz helped to create in Warsaw during the last months of his life. He wrote special poems for children and even donated his most valuable possessions to aid the needy and homeless. Jacob Dinezon felt obliged to continue this work which Peretz began.

Peretz’s death had a shocking impact on Jacob Dinezon. He could not find his place. He desperately missed Peretz until he died and found his eternal rest near Peretz. As it is known, he is buried together with S. An-ski under “Peretz’s Tomb.”