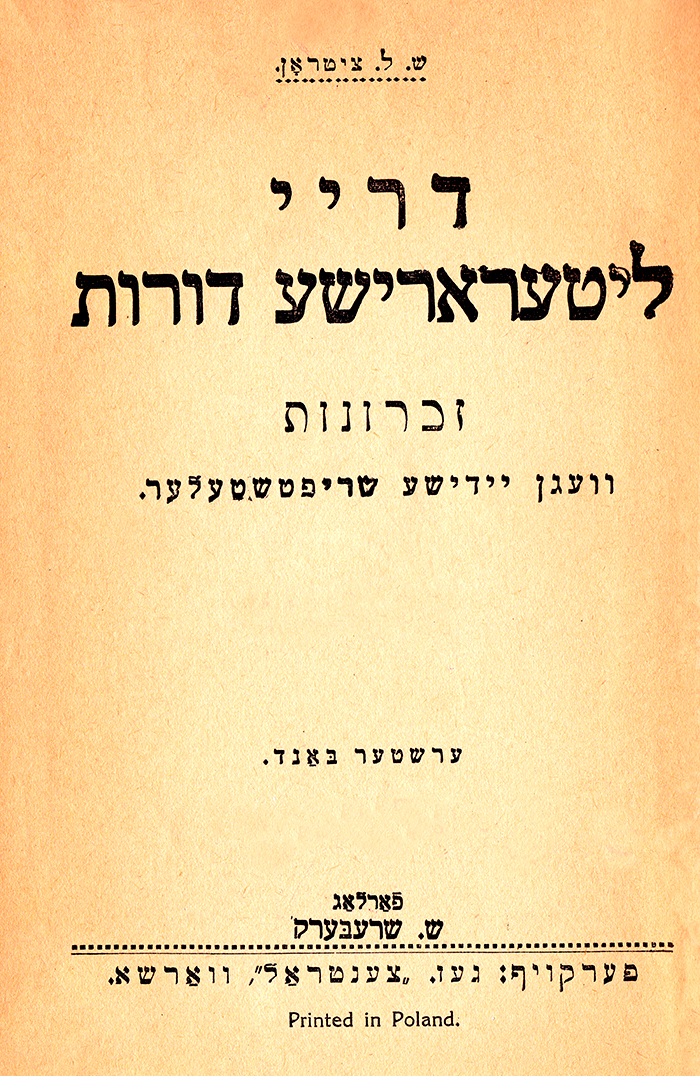

By S. L. Tsitron (Zitron)

From Dray literarishe doyres:

zikhroynes vegn Yidishe shriftshteler

(Three Literary Generations:

Memories of Yiddish Authors)

Vilna: Sh. Shreberk Publishing House, 1920

Pages 56-104

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Translated from the Yiddish by

Archie Barkan

Transcribed and Edited by

Robin Bryna Evans

Additional Editing and Translation by

Mindy Liberman

Volume 1: Memories

To the Reader:

There is a saying by Goethe: “Who wishes to understand the poet must go to the poet’s land.” The intent is that in order to properly penetrate the artistic nature of the poet, in order to understand the full significance of his creative power, in order to have a correct conception of the innermost strengths that have driven him to his literary calling—for this it is not enough to have simply read what he has written and to be versed on his works. In addition, one has to be able to accurately study the environment in which the poet has lived and created. In addition, one has to also be able to accurately study the circle in which the poet moved and which, to a certain extent, consciously or unconsciously, influenced him in one respect or another.

Nations of the world, interested not only in literature but also in those who create it, have for a long time now thought of Goethe’s saying that I quoted above as an axiom, a great truth. They write individual monographs and entire volumes not only about books but also about their authors. Various biographical materials and memoirs are used for that purpose. Through them, the writer’s personality is brought to light, and the dynamic intellectual strengths, the wellsprings of his artistic creations, are researched in the same way. These materials are carefully collected and prepared, first for the biographer and then for the literary historian.

For us, for the time being, the situation is completely different. We possess certain books about literature; we have critical discourses, whole works, about books by this or that important author. However, we do not have any works, especially no larger monographs, about the principal writers, the creators of our literature. Even more, we have no detailed, exhaustive biographies of our greatest and most significant folk writers, such as Abramovitsh, Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, and so on. What we have today in that area is very poor and insignificant and can in no respect serve as a guide for the literary researcher of the future.

And that this particular aspect of historic literary research is virgin territory for us, an untilled field, is not because of a scarcity of materials due to a deficit of news or details about the lives of our writers and their various material and intellectual life experiences. We lack the interest that you see in other peoples in collecting and gathering reminiscences about great writers and in recording the conversations that we had the opportunity to have with them about various issues and circumstances. We don’t consider that the memories and conversations might one day be the only keys to the critical-psychological research on this or that important and epoch-making writer who greatly influenced the entire developmental path of Yiddish literature.

With the current publication of my own recollections, I am making, if I am not mistaken, the first attempt in the area of memoirs in Yiddish literature. My memoirs include approximately twenty of the greatest and most important Yiddish writers, the majority of whom were significant not only for their own time. I myself experienced most of the events that I relate here, and the rest were related to me by the most suitable sources upon which I could depend with complete certainty. The majority of my recollections, especially the dates of the facts and conversations, have always been recorded in my notebooks. The rest were all completed by my memory that has never, until now, led me astray.

There may be some readers who think that this or that detail of my memoirs is not interesting to the general public. But in my opinion, the smallest and the seemingly most unimportant fact can sometimes add, for the biographer or the literary critic, an entirely new and sharply pertinent characteristic to the human-ethical physiognomy of the writer in question.

This was, for me, the only criterion for compiling and publishing these memoirs.

The Author.

Vilna, end of March 1920.

Part III

In the mid-1870s, Jacob Dinezon was the most popular of the Yiddish writers. His first novel Ha-ne’ehavim veha-ne’imim, oder, Der shvartser yungermantshik (The Beloved and Pleasing, or, The Dark Young Man), was on the table in almost every Jewish house. But three or four years later, when Shomer (Nokhem Meyer Shaykevitch), Bukhbinder (Avrom Yitshok), and others like them began to flood the Yiddish world with their shund novels (literary trash), little by little, Dinezon began to lose his popularity until it appeared his name would be entirely forgotten.

At the beginning of the 1890s, Dinezon’s name again surfaced for the Jewish public, but this time, not so much for his own sake but because of Peretz, his most intimate friend. From then on, they didn’t speak about Dinezon by or for himself but as Dinezon, the closest friend of Peretz. Peretz became the sun, and Dinezon the accompanying star.

Now too, after Dinezon’s death, they place Peretz in the center of all the published obituaries and memoirs. All those who had anything to say or relate about Dinezon concentrated their narratives on the person Peretz. The impression prevails that before the nineties, before Peretz, Dinezon was a blank sheet, a kind of tabula rasa.

In truth, however, that is not the way it was. Those who knew him well always regarded Dinezon the person as an interesting personality, even without taking into account that he was the first novelist of Yiddish literature.

In truth, however, that is not the way it was. Those who knew him well always regarded Dinezon the person as an interesting personality, even without taking into account that he was the first novelist of Yiddish literature.

For example, I, who first became acquainted with Dinezon through letters and then personally in the late 1870s, found just the opposite. In a number of ways, in the years before Warsaw and also in the first three or four years after he came to Warsaw, Dinezon was a much more interesting, original, and striking individual. He made a distinct im pression with the contrasts in his personality: on one side, softness and sincerity were the main characteristics of his personality as expressed in the constant, honey-sweet smile on his lips and, on the other side, he was introspective and somewhat melancholy with a kind of stubborn reserve.

I must note here that under Peretz’s influence, Dinezon became talkative, lively, and open-hearted. I remember Dinezon very well when he was still very stingy with words and listened more than he talked. Sometimes he would be lost in thought for a while and then suddenly awake as if from a dream. I recall another detail: if Dinezon ever exceeded his usual number of words, it was only when he carried on a conversation with someone about Mohilev and the people of Mohilev. Mohilev was the only subject that he liked to return to at any opportunity and about which he spoke with a special interest and great enthusiasm. It was quite easy to notice that he did not want to and could not forget Mohilev because it possessed something baked deeply into his heart. And this was not a wonder at all for those who knew—and I was one of them—that Mohilev was the cradle and grave of Dinezon’s lost dreams of youth and his youthful hopes that vanished in a cloud of smoke.

In Mohilev, Dinezon endured and experienced much emotionally, and his experiences left deep marks that only began to be smoothed over much later in his life, almost without him noticing it himself. A time came when you’d hear Dinezon talk about Mohilev very rarely from time to time.

A second city took its place from then on, although on a much smaller scale. He often liked to talk about it as well. It was Kiev. Kiev also left Dinezon rich with experiences, but his Kiev experiences were of a different nature entirely and not as tragic as those of Mohilev. These differences in his experiences were easily recognized by the tone with which he spoke about them. When speaking about Mohilev, he showed a profound calm that, at times, evolved into a mood of pathos. The Kiev impressions resulted in a nervous exasperation and strong bitterness.

I don’t know whether Dinezon ever recorded his personal experiences anywhere. He did say that he was writing his memoirs, but as far as I know, he did not. He did not record anything more than the few reminiscences about his childhood years that he published in Der Pinkes (The Chronicle) and Der Yud (The Jew).

The Dinezon that I knew was in that category who thought of certain special fenced-off corners of their past as the “holy of holies.” They do not willingly give outsiders a glimpse. I am not even certain if he made an exception for Peretz in this regard. I think that now, after Dinezon’s death, as he is no longer an individual and becomes part of the history of our literature and culture, we can—not only can, but must—lift the curtain on that which until now was hidden from the world, and reveal what our folk writer, beloved by the people, carried for his entire life bundled up in the depths of his soul. We must do this in order to give the future psychologist-critic the key to understanding Dinezon’s great and powerful moral personality that certainly had an influence on the very essence and development of his literary activity.

In the chapters to follow, I will relate a few of the more characteristic episodes of Dinezon’s personal experiences. These are facts that I heard at various times from people who knew Dinezon well as a youth, or I personally experienced myself. However, I find it necessary to first bring forth a few short notes from his biography.

His father was a scholar and a failed shopkeeper in his final years and died when Dinezon was twelve years old. At that time, his parents lived in Nay Zhager (Kovno Gubernia), well known for its wise men and scribes. Dinezon received a true orthodox education. By the time he was twelve, he had already studied with several teachers and was well-versed in the Gemara and commentaries on the Talmud. As Dinezon himself relates in his memoirs, it was at this time that he began to develop the desire to write.

After his father’s death, an uncle on his mother’s side who lived in Mohilev on the Dnieper River—Isaac Eliashev was his name—took him in. Eliashev was a God-fearing Jew but no stranger to secular knowledge and had a reputation as an excellent mathematician in the city. At first, he enrolled his gifted little nephew in a cheder with a brilliant teacher. Afterward, he brought him to the yeshiva of a certain Reb Abba, a fine Talmudic scholar with a sharp mind. If there was a capable young man or a child prodigy in the city, he studied with him. Dinezon was considered one of Reb Abba’s best students and one of the best in Mohilev in general, and he made a name for himself in learned circles.

When Dinezon turned seventeen, he studied by himself in Shmerl Zuckerman’s study house. This Shmerl Zuckerman, an Orthodox scholar with the finest pedigree, was very rich and known throughout the entire region as a man of charity who possessed a generous hand. He especially befriended poverty-stricken scholars and good students. His house served as a gathering place for rabbis and prestigious Jews of all kinds. His large library was also famous all over Lithuania for containing all kinds of Jewish tomes and rare items.

Zuckerman was a leader in the community and a trustee in many of the most important organizations and social institutions, so nothing was done in the city without him. His wife, Mirl Khateyvitsher (that is what she was called by the people after the shtetl of Khateyvitsh in the Minsk Governate where she was from) or Mirl Sharlatova (her maiden name), was also known as a fine example of a Jewish woman.

This Shmerl Zuckerman built, at his own expense, a beautiful study house where the finest young people of the city sat and studied day and night. As a result, these young people became his intimates and were always welcomed in his home and granted the freest access to his library.

As mentioned, Dinezon, too, was able to study in Zuckerman’s study house. His reputation among the city’s scholars helped him achieve this privilege. He soon became a frequent visitor to Zuckerman’s home and especially to his library. Being a great lover of books, Dinezon threw himself into this library with great enthusiasm. Not quite seventeen years of age, he had already read (Judah Halevi’s) Kusari (Book of the Khazar), Moreh Nevuchei HaZman (The Guide for the Perplexed of This Time) by Rabbi Nahman HaCohen Krachmal, Lemberg, 1851, and similar philosophical works. These books had an impact on him in the sense that he began to think about phenomena in the present and the past and to investigate old and new historical problems as much as he was able, according to his rather poor intellectual development and mental ability at that time.

Also at that time, Dinezon spoke completely by chance with a young man from Zuckerman’s study house, who quietly gave him to read for the first time some of the new Hebrew books of the Haskalah: books by Mordekhai Aharon Gintsburg, Avraham Mapu, Kalman Schulman; and also Smolenskin’s Ha-Shahar (The Dawn). These works, especially the Shahar pamphlets, made a great impression on him. The result was an upheaval to all his traditional views and beliefs. He began thinking about his future and the goals in life for which he must prepare. The first decision he made was to leave Zuckerman’s house of study and Zuckerman’s circle in general and obtain a secular education.

But Dinezon was not able to immediately act on his decision. Long before, he had left his Uncle Eliashev because he didn’t want to become a burden, and was making a living by tutoring respectable young men in the Talmud. Because of this, he was obliged to remain in Zuckerman’s study house in order to preserve his reputation as a good student. However, he used this time to perfect his Hebrew and Russian as well as other studies.

Dinezon soon began to send reports about minor events in Mohilev to Ha-Magid (The Preacher). He also tried a few timed to write about similar topics for Ha-Melits (The Advocate). In this way, he obtained a reputation in Mohilev as an expert in Hebrew. This gave him the opportunity to acquire students to whom he taught the He brew language. Only then did he abandon Zuckerman’s study house. However, he didn’t completely break off his relationship with Zuckerman’s house, partly because of the library and partly because, even though he was a maskil (a follower of the Jewish Enlightenment) with maskilic ideas, he either did not wish or found it difficult, to show this openly in public.

In this detail, Dinezon was in contrast to most of the other young maskilim of that generation. Before their “enlightenment” even began to crystallize and develop a clear, substantial character, they presented it to people while it was still raw and half-baked. As the Russians say, “On show so people will know.”

In order to follow Dinezon step-by-step from then on—this was at the beginning of 1874—we have to understand the intellectual situation of Mohilev at that time.

I have already commented [1] on the remarkable fact that in such an extremely fanatical and culturally backward city as Mohilev, which in addition had no train service until only a short time before and was cut off from the rest of the world, the Jews were infiltrated by the so-called kazshone (commonplace) Haskalah almost before anywhere else, but also Marxist socialism in its various forms. The first Jewish friends of the Narodovoltses (People’s Party) were born in Mohilev or finished the Mohilev gymnasium (high school) as, for example, Eliezer Zuckerman, Axelrod, and the Leventhal brothers.

An epidemic of runaways broke out among the youth of Mohilev. Young men and women took bag and baggage, sometimes just like that, and ran away from their parents. They studied in other cities in order to become independent and transform their lives according to the new modern ideas that they had absorbed in secret from the Russian socialist pamphlets that were smuggled into Mohilev in various ways, mostly from Kiev. Some parents tried to chase after their children and sometimes succeeded in bringing them home, as with Eliezer Zuckerman, mentioned above, whose father caught him in Gomel and brought him back to Mohilev (from where he fled again a short time later). And others, hard-hearted, gave up on their “corrupted” sons or daughters right from the first moment and stayed put.

And at that time, among the Jewish population of Mohilev were three or four wealthy and intelligent houses that strongly supported the young people who desired to escape. In these houses, the young men and women, candidates for running away, were provided with everything they needed for the road: clothing, documents, and the like. The educated Christian sector of Mohilev also supported this flight by young Jews. Even local administrators who knew about the movement and were strongly sympathetic to it did as well.

Also in Mohilev at the time were young Jewish people who had already been tempted by the new Socialist-Materialist thinking of Pisarev and Chernyshevsky, who nevertheless remained where they were and did not join the Socialists. True, the new ideas influenced them, but the influence was in exactly the opposite sense. They, too, went “out among the people,” according to the latest resolution of the socialists at the time. But they reached out to the Jewish population rather than the Russian, as was the custom among the Jewish socialists. They went among the Jewish masses to spread learning and knowledge and to make them useful members of society. Toward that goal, they volunteered to become unpaid teachers in the city’s Talmud Torah, where hundreds of children from the poorest sectors studied. Into this dark nest, they brought light. They were not only teachers for the children but also faithful fathers who took care of their physical state, material needs, food, drink, and proper lodging.

This was not that easy for them. For a long time, they had to wage a bitter battle against the reactionary elected officials of the Jewish community council, who later became famous, those very sad heroes of the so-called mapelya (deep darkness) in Smolenskin’s stories, who absolutely did not want to carry out a new order in the Talmud Torah. (See page 3 in P. Smolenskin, who had developed the plot of his major novel, Hatoe be-darkhe hahayim (Lost in the Paths of Life) in East European Jewish towns with names such as Madmena (Dunghill, Bog), Mapelya (Darkness), Shakula (The Bereaved One), etc.)

The victory was won not by the dark forces, not by those bats, but by the energetic young people who chivalrously fought under the banner of the Haskalah and the spirit of the times. Jacob Dinezon, too, belonged among these young fighters of that time. Dinezon taught Bible and Hebrew in the Mohilev Talmud Torah. Soft and tender-hearted by nature, he shared his softness and tenderness with the children. Through his initiative, the Talmud Torah organized a kitchen where the children received daily lunches instead of having to go out to people’s houses for meals, as was the custom. The Mohilev community council considered this kitchen a superfluous luxury and didn’t even contribute a broken pfennig to it. Dinezon took the first step by giving one hundred rubles that he had saved from tutoring, and he and his friends collected from other donors for the rest.

Among Dinezon’s friends who worked with him as teachers in the Mohilev Talmud Torah were also the above-mentioned Eliezer Zuckerman, who later joined the Socialist Revolutionaries, and the now well-known writer Mordechai Ben-Hillel Hacohen.[2]

These particular facts were told to me by Dinezon himself, and some were related in an embellished form through his friend Eliezer Zuckerman’s fictional account.

From here on, I turn to my memories.

I

Among the wealthy and intelligent Mohilev houses mentioned above that supported the young people running away at that time was the house of the wealthy Yeshuah Menachem Hurevitsh, which was well known throughout White Russia. He was a Jewish merchant who constantly dealt with immense enterprises and, for this reason, was often away from home. He was reputed to be very respectable and conscientious as well as knowledgeable and practical. He was kind and compassionate by nature, with a very strong desire to do good for people and to help the needy and the oppressed.

His wife Badana played an especially large role in Mohilev. She was the daughter of the prominent and wealthy Vilna maskil Reb Josef Bezalel Harkavy, son-in-law of the world-famous Gaon, Reb Shemu’el Strashun, and the older sister of the very well-known Vilna printer Devorah Romm. She, Badana, well-educated and refined, managed a Jewish and, at the same time, truly aristocratic house. She gave her children (five sons and an only daughter) a well-rounded, modern ed ucation. They all attended the Mohilev gymnasium and supplemented their education at home at the same time. Because of Badana herself, and also because of her highly developed children, her house became a center for all the Jewish Mohilev young people who thirsted for knowledge. The intelligent Jewish youth often gathered at the Hurevitsh house to carry on passionate discussions and disputes about various questions of literature and life. They would pour their hearts out to one another, build plans for the future, and amuse themselves with playing, singing, and dancing.

During the time when the Jewish population of Mohilev began the general sturm un drang (emotional drive) for education, and many former full-time yeshiva students began studying on their own, Badana’s household provided them with free teachers and textbooks. A little later, when they began to run away from their fanatical parents, Badana’s house became one of the gathering places where those preparing to flee sought advice about the possibilities of their journey and said their farewells to friends and acquaintances. In Badana’s house, they could obtain illegal literature, various forbidden socialist books, and brochures like Chernyshevsky’s very popular novel What Is to Be Done? and so on.

Little by little, socialism became further entrenched in the Mohilev Yiddish intelligentsia. It happened that not only children of the middle class but also boys and girls of the “upper ten thousand” began joining the Socialist-Narodniks and mixing with the Russian people. The first to leave were children—for the most part, young ladies—from the homes of the rich intelligentsia, where earlier they had sympathized with and strongly supported the escape movement of the middle classes. And they did not leave alone, but with lovers accompanying them, mostly Christians, taking with them their whole trousseaus and sometimes also jewelry. It was told at that time that some of the fathers whose children ran away and were already adults and betrothed, paid with their lives.

Badana Hurevitsh’s house was spared from this very sad fate. Her wise alertness and motherly supervision resulted in her children not going away with this stream but rather remaining at home. Four of her five sons followed in their father’s footsteps, and in time, became big merchant capitalists. Only one joined the socialists, but he did not remain in Russia and emigrated.[3] She sent her only daughter, who possessed great musical talent, to Vienna, where she entered the conservatory.

This Badana Hurevitsh had taken Jacob Dinezon into her house as a Hebrew teacher for her children. From several people, she had heard of Dinezon’s extensive knowledge of the Hebrew language, about his teaching activities and self-sacrifices in the Talmud Torah, and the respect and love that he enjoyed everywhere he went. Looking for a Hebrew teacher for her children, she immediately settled on him. He made an especially strong impression on her with his opinions on education that he expressed in their first conversation when she invited him to her home. Dinezon considered it quite a respectable position and very willingly accepted it.

With his gentle behavior and modest character, he immediately won over everyone in the house. He quickly found favor with his young, intelligent students through the interesting and learned conversations on various topics he held with them and, sometimes, with their whole circle of friends. They saw that this former serious student from Shmerl Zuckerman’s study house was very well-read and advanced. He passed judgment about everything with as sharp and logical a mind as any “graduate”—the ideal of the educated youth of Mohilev at that time. In this way, Dinezon became a member of Badana Hurevitsh’s house from the very first.

Both the parents and the children depended on him. Nothing, even the most secret household situations, was hidden from him. They quite often consulted with him on many issues. Badana’s husband considered Dinezon a deep-thinker and discussed with him questions of com merce that especially interested him. More than once, Dinezon was sent by the Hurevitsh family as their representative to various cities on business and family affairs.

During one of these trips, Dinezon became a Yiddish writer. This was at the end of the year 1874. At that time, with the full authorization of Badana Hurevitsh, Dinezon went to visit her sister Devorah Romm in Vilna on a family matter. Dinezon remained in Vilna for two weeks, staying with the Romms the entire time. There he had the opportunity to meet a few of the most noted Yiddish writers of the day, such as Adam HaCohen Levinson, Kalman Schulman, Isaac Meyer Dik, and others, who were regular visitors at Devorah Romm’s house. Dinezon became friends with Dik in particular, and the two carried on conversations about writers and books for hours on end. Dik told Dinezon about the widespread distribution of his books, their popular success, and the great profits they brought him. At the same time, Dik complained strongly that Devorah paid him just a few groshen for his books, and if not for his wife’s outside earnings, he wouldn’t have enough to live on. Dinezon had always been a lover of literature, and from the time his letters from Mohilev had been published in Ha-Magid (The Preacher) and Ha-Melits (The Advocate) newspapers, he had never stopped dreaming of reaching a higher level of writing. During the entire journey back home to Mohilev, he thought about creating some sort of distinct work. And although he had mastered the literary Hebrew style and appreciated that language with a special love, he nevertheless decided from the first minute that whatever he wrote would only be in Yiddish.

As Dinezon once explained to me during a conversation, he decided on Yiddish for the following reasons: first, he was influenced by his discussions with Dik, who had emphasized many times that writing for the masses was most important. Second, the milieu in the Hurevitsh house, where the special worries of the people never left the daily agenda, brought the interests of the people much closer to his heart.

Third, since he often had dealings with the hundreds of parents of the Talmud Torah children, he sensed in himself a particular ability to converse with and influence the masses. And fourth, he had already attempted to write two natural science brochures about thunder and lightning, snow and rain, and others as overviews for his Talmud Torah students. At the time, experts told him that their literary style was successful enough to be published. Thinking about this issue enroute, he arrived back in Mohilev with a clear decision to devote his free time to writing a Yiddish work—a work of literary fiction.

Dinezon began to look for an appropriate theme for a story. Such a theme came to him quickly. In Mohilev at that time, the following very tragic story occurred. One of the city’s richest men, an ultra-fanatic, betrothed his daughter against her will to an illiterate, ignorant boor from a good family. The girl, however, strove for an education and had entirely different ideals. She was a frequent visitor to the circles at Badana’s house and was considered one of the more intelligent members. She was also discovered to have a flair for poetry and was advised not to neglect this talent. In that circle, they also knew that she was in love with a cousin, a high school student. No matter how much the girl complained and pleaded with her father to have pity on her young years and not force her to marry against her will, nothing helped. When the circle at Badana’s house learned of the story, they advised her to run away like so many others.

Nevertheless, she was too weak for that. She loved her mother very much and could not make up her mind to leave her. It was also difficult for her to part from her beloved. Her father continued to drive her toward the wedding without pity, and her sufferings became truly unbearable. Everyone saw how she faded from day to day. She expressed her despair in Russian poems and passed these around among her friends in the circle. However, no one could help her. Her father was merciless; in addition, he was an official in the community, and there were no measures that could be taken against him. Any day they expected her to take her own life.

One day, however, she came to Badana’s, apparently calm and quite cheerful. She said that since she didn’t have the strength needed to quarrel with her father, she decided to give in to his demands and marry the man he had chosen for her. She hoped, however, that after the wedding, she would have a strong influence on her husband and change him completely so that in her hands, he would become an entirely new man. The girl soon stood under the marriage canopy with her father’s can didate and, almost the next day, began to “remake” her husband, as she phrased it. She herself began to teach him various subjects and instructed him in etiquette and how to act among people. She also brought him to Badana’s and introduced him to the members of her circle.

However, it appeared that her efforts were for naught, and her in fluence went up in smoke, for this boorish man remained a boor. Once, during a visit to a couple she knew, he caused an unheard-of scandal that afterward caused a buzz throughout the city. Returning home in great misery, she went into the stable and hanged herself.

Dinezon used this piece of sad Mohilev reality as the theme for a story in two parts called Beoven avos (For the Sins of the Fathers). When this story was ready, he read it to Badana’s circle, where it made a great impression on everyone. The general feeling was that Dinezon had many sparks of artistic talent and should not stop midway. Dinezon immediately sent his story to Vilna, to Devorah Romm, who handed it to the censor. There was at the time, a censor for Jewish books named Vohl, a former teacher at the Rabbinical School. Coincidentally, it so happened that Vohl’s wife was a close relative of the cruel father in Mohilev, and both she and her husband knew the whole story. This was the real reason that Vohl forbade the publishing of Dinezon’s Beoven avos, even though he had made corrections and found another excuse.

I must comment here that the same story, with almost all the details, was reworked in Hebrew a year and a half later by Dinezon’s former friend, the later socialist revolutionary Eliezer Zuckerman, who now lived in Vienna. It was published in the form of a diary under the title “Oylam hafukh” (“An Upside-Down World”) in Smolenskin’s journal Ha-Shahar. [4]

Dinezon took the banning of his first novel very badly. Speaking with him once in Warsaw about this unpublished story, I heard the following interesting observation from him: “Today people call me, ‘The creator of the Yiddish sentimental novel.’ Had they read my Beoven avos, however, they would not have come to that conclusion. My Sins of the Fathers was the height of realism and possibly too realistic. This was an accurate version of the reality I witnessed myself and in which I participated in a certain measure. I became sentimental after this. I became sentimental after this. A later chapter in my life made me sentimental.”

I understood quite well the meaning of these words. The reader will have this explained in one of the future chapters.

It did not take long for Dinezon to begin writing a second novel. This was his great novel, Ha-ne’ehavim veha-ne’imim, oder, Der shvartser yungermantshik (The Beloved and Pleasing, or, The Dark Young Man), written with such energy and speed that it was ready in less than a month. This time, he traveled to Vilna specifically on account of his novel. He wished to be there himself to see whether the book would come out intact from under the censor’s hand. The Dark Young Man found favor in the censor’s eyes, and he passed it without any trouble. [5] Devorah Romm immediately turned it over to the printer.

As Dinezon once told me, when the book came back from the censor, he read it in two consecutive evenings for a small group of Devorah Romm’s acquaintances, all from the Vilna Yiddish aristocracy. Isaac Meyer Dik was also among them. As he finished reading, everyone in attendance expressed an opinion about the story.

The general impression was very favorable. Dik came over to him and said, “I would not have been able to do this. Such a long book with so many characters! Where does one get the strength to keep all that in one’s head? I am accustomed to dealing with only one person; you’ll find two in my writing only once in a blue moon. Furthermore, I find your book a little too gloomy. The seasoning that tickles the funny bone is missing.”

II

After Dinezon published his very popular The Dark Young Man, he had no idea that fifteen years would pass before he would publish a second book. He thought the opposite, that from then on, he would continuously write and publish and publish and write. The last time he was in Vilna, he had even signed an agreement to that effect with Devorah Romm. In fact, only a short time after The Dark Young Man appeared, he took steps to write a new novel called Avigdorl.

Dinezon was still at this time, like all the maskilim of that period, a strong supporter of Hebrew and very loyal to Hebrew literature and its writers, especially Smolenskin, whom he, in fact, revered.

Therefore, he wanted to show the maskil world that his under taking to write in Yiddish did not mean he had completely cut himself off from the Hebrew language of the Haskalah. He intended to prove this by writing a long article in the periodical Ha-Shahar in which, in passing, he praised to the skies Smolenskin, Lilienblum, Chaim Zelig Slonimski, the editor of the Hebrew journal Ha-Tsefirah (The Dawn), and others. [6] He anticipated that after this article, where he declared himself an unequivocal friend and lover of Hebrew, he had done his duty by his maskilim and could calmly and assuredly continue his Yiddish work without breaking from the maskilim of that generation. But to his surprise, this article brought about exactly the opposite results. Furthermore, not only did his article not reconcile him with his friends, the maskilim, or bring him closer to them, but it actually estranged and pushed him away from them. It even led him to reject Yiddish as well, at least for some time.

In response to Dinezon’s article in Ha-Shahar, mentioned above, where he discussed a particular Yiddish journal, Smolenskin included this phrase, “A maskil who writes in Yiddish is like two opposites in one person. Those who think you have to have some ability to write in this corrupt language are mistaken.”

Dinezon once told me the following with respect to the impression Smolenskin’s remark had on him. “At that time, I was a child of my generation, a maskil with the conceptions of a maskil. I didn’t dare write in Yiddish without a feeling of fear that what I was doing might be a stain on the honor of the Haskalah, which looked down on ‘jargon’ from the beginning, as is well known. I had even overcome the folk instinct, that instinct which is bound and woven into the mother tongue. Thus, I couldn’t free myself from the thought that with the writing and publishing of The Dark Young Man, my Haskalah became more ordinary and would not become that ‘daughter of heaven’ for which I had fought with such fire against the dark forces while I was a teacher at the Talmud Torah in Mohilev.

“At the time, I believed I could smooth things over in the article that I wrote for Ha-Shahar. In it, I stood up against the injustice by our best Hebrew writers. Suddenly, none other than Smolenskin comes along, the very man who had long been my idol. I had always considered his words to be absolute, like the laws handed down to Moses from Mount Sinai. He decreed that it was shameful for a maskil to write in Yiddish, that anyone could write in Yiddish, and that you didn’t need any talent whatsoever. True, with that remark, he even lessened my desire to write in Yiddish, but on the other hand, I took my revenge on Smolenskin and tossed my Hebrew pen aside for good.” [7]

“On the whole,” Dinezon concluded, “Smolenskin’s remark, directed at my article, was like a bomb. It seemed to me that from the very be ginning, his intention was to target me because of The Dark Young Man. Not being very courageous at that time, it unnerved me even more, and as a result, I walked around very confused for a long while.”

Dinezon was heavy-hearted and in very low spirits. He had not recovered from the very stressful and depressing conditions in which he found himself during the previous three-quarters of a year. Writing his first novel, The Sins of the Fathers, still feeling deeply the drama of the girl who was forced to part from her lover, he discovered one fine morning that he, the chronicler of someone else’s love story, was in love himself. He realized that he was not indifferent to his student, the only daughter of Badana Hurevitsh. He was very happy during the hours he was teaching her and wished that these hours would go on forever. When she played the melody to a Mikhl Gordon song that he had taught her on the piano, he was in seventh heaven, and he always felt like he wanted to be near her, near her alone. He met many young ladies almost daily at the Hurevitshes, and although some might be prettier, more intelligent, or even more educated, he set his heart on her.

He loved with all his youthful passion but carried his love in his heart, hidden from everyone. No one saw it, and no one noticed. His love was precious and holy to him, and he tried not to make it common with irrelevant thoughts. The most sentimental expressions of love in The Dark Young Man were written under the influence of his inner personal experience at that time. Between the lines of this novel were, here and there, mirrored the nervous stirrings of his deeply loving soul. Here and there echoed the vibrating trembling of his most secret strings. But not one reverberation escaped from his mouth, not even the weakest echo of his feelings. In this way, he guarded and watched over them.

Of course, this couldn’t last long. Like the ripe apple that falls from the tree, there came a time when Dinezon could no longer control the feelings he kept constantly locked up b’chadrei chadarim (in the most secret chamber.) Even his face began to show telltale signs, and it became obvious that in his student’s presence, his appearance was very different, and his behavior toward her took on an entirely different character, much friendlier and more intimate. This was first noticed by strangers, outsiders, and especially by the members of Badana Hurevitsh’s circle. The household itself did not notice, and least of all, the loved one herself.

This situation stretched on for about half a year. Dinezon began to suffer. He suffered because she, to whom all of his dearest and holiest feelings and dreams belonged and about whom he didn’t stop thinking day and night, did not even begin to understand what was happening to him. She had no inkling what he was enduring. After many emotional experiences and wars within himself, he decided to reveal his heart to her. Although, according to his knowledge of the Hurevitshes and their outlook, he knew that this could not possibly bring any positive results, he still didn’t want his love to remain a secret from the person to whom it belonged. Days and weeks passed, yet he couldn’t act on his decision. He was too weak for this and too shy. In the meantime, there was talk in the house about the daughter’s leaving for Vienna.

This idea developed for the following reasons. First of all, Badana feared that with the growth of the Narodnik movement in Mohilev, her daughter too would, in the end, fall prey to the running away epidemic. Second, so that she could complete her musical training there. Because of this matter, they held a special family meeting that Dinezon, as always, was invited to attend. It is easy to imagine how Dinezon felt participating in this meeting. He was among the first, however, to find it necessary and urgent for her to travel to Vienna.

The last days before her departure from Mohilev were days of unbearable suffering for Dinezon. How many times did he resolve to express his feelings to her? He once managed to blurt out, “I have something important to confide in you.” She immediately took an interest in knowing what he wanted to say, but he remained silent and didn’t say a word.

And so his student went off to Vienna on the designated day, and Dinezon remained with his secret.

In order to continue my notes about Dinezon, I find it necessary to relate a few facts about my own personal life. In the month of May 1876, having just ended my studies at the Volozhin yeshiva, I came to Vienna to learn, or as it was known then, to study, on the advice of Smolenskin, the shining star and guide of many Talmud-educated young people of my age. One of the wealthy members of the Minsk intelligentsia, Wolf Rapaport (son of the well-known Reb Sussele Rapaport), knew me well and was very interested in my secular education. He had written a recommendation on my behalf to one of his acquaintances in Vienna, someone named Rosenstein. This Rosenstein, a very rich man, had lived in Mohilev about fifteen years earlier. In time, his fortune changed, and he lost everything. He then moved to Vienna with his family and, having a reputation from home for great honesty, be came a commissioner-middleman between Austrian businesses and the big Jewish trade firms in Russia.

Rosenstein’s family (a wife with two grown daughters and a younger son, a student) was very intellectual and served as a center for the Mohilevers residing in Vienna, especially the young students. Smolenskin was also a frequent visitor, as he was tied to the Rosensteins through shared memories of their time in Mohilev. When Smolenskin was a young singer with the Mohilev city cantor, he would sometimes come with the cantor and other choirboys to the Rosensteins on the Sabbath or holidays. At that time, Rosenstein was one of the trustees, and they would sing various melodies in his honor. I remember that Smolenskin liked to mention it and Rosenstein was very proud of this.

The whole first month after my arrival in Vienna, I lived with this Rosenstein family. During that time, I became acquainted with all the Mohilevers who regularly visited the Rosenstein house. Also among them was the present-day Hebrew writer and popular Kiev nationalist activist Moshe Kamyonski, who was a socialist revolutionary, and Eliezer Zuckerman, already a former socialist revolutionary. [8] Also, Badana Hurevitsh’s daughter, Dinezon’s ideal, came as well, but in truth, less often than the others. The following small details have remained in my memory to this day about young Miss Hurevitsh. She was of average height and a brunette, and Zuckerman always sulked and almost never spoke to her. Now I understand that he did that at the time due to his built-in hatred of the rich. I remember another detail about her. I was told that at Smolenskin’s wedding about a half a year earlier, she had accompanied the dancing on the piano, and the crowd left enchanted by her playing, predicting a glowing musical future for her. Clearer than everything else, I remember the fact that in the Mohilev circle, whenever they talked about her among themselves, they almost always mentioned Dinezon’s name. At the time, I didn’t know and was also not interested in knowing the subject of this conversation. Later, when I learned the facts about Dinezon’s love epic, I understood that for Rosenstein’s daughters, who corresponded with their Mohilever friends, Dinezon’s romance was no secret. As a matter of fact, everyone in the circle knew about it, and it was a topic of conversation. I also have not forgotten that one of the Mohilevers related at the Rosensteins that Dinezon had asked Smolenskin in a letter whether he should come to Vienna and whether he would have good prospects for getting settled there.

Miss Hurevitsh spent two years in Vienna and then finished her musical education in Paris. During that time, Dinezon wrote to her many times, but always on only one subject, music, as well as he understood it as a dilettante, since music interested her more than anything else. Not even the smallest hint of his feelings could be found in the letters. This was the result of his strong inner struggle earlier.

Three years after that, she returned to Mohilev. Before that, Dinezon frequently determined to leave his teaching position with the Hurevitsh family and move away from Mohilev. But he was also too weak for that. He had come to love the Hurevitsh house and the whole family. He felt very close to them, and so with all his strength, he always drove away any thoughts of leaving. Not long after the Hurevitsh’s daughter returned from abroad, they began talking about matches. Every potential prospect was discussed in a family council, and Dinezon was invited to everyone. The young lady knew about this and quite often said to Dinezon in jest, “Look, Teacher, sir, don’t sell me short.” This was during the time he still loved her with all the passion of his soul.

However, Dinezon was destined to suffer another very difficult trial. One day, Hurevitsh’s nephew visited Badana Hurevitsh. He was a young recent graduate of a doctoral program and the son of Deborah Romm. The guest soon fell in love with his cousin, and in no time, Dinezon was traveling to Vilna, fully empowered by the Hurevitshes to make arrangements for the marriage.

When Dinezon returned from Vilna, he became ill and did not leave his bed for three weeks.

III

In 1877, I left Vienna and traveled to Breslau with the intention of entering the rabbinic seminary there. I became acquainted with a seminary student, a young man from Borisev by the name of Pesach Ruderman. This Ruderman was then on the staff of Ha-Shahar and, according to the Hebrew reading public, possessed a promising talent as a columnist.

One day, Ruderman told me a story about receiving a letter from the author of The Dark Young Man asking him to send the seminary’s program because he wanted to come to Breslau to study to be a (non-Orthodox) rabbi with a doctoral degree. Ruderman fulfilled Dinezon’s request and sent the program catalog. From then on, he began to correspond with Dinezon. Their first letters had an ideological character. They discussed Hasidism.

Born a Hasid, a Chabadnik, Ruderman passionately defended Rebbe Shneur Zalman of Liady against the Goan of Vilna. Dinezon, an ardent Misnagid (opponent of the Hasidic movement), held fast for the Goan of Vilna. Dinezon’s article in Ha-Shahar, which I mentioned in the preceding chapter, led Ruderman to this topic. In this article, in which Dinezon touched on Hasidism in a few lines, he mentioned Ruderman in passing and expressed an opinion opposing him.

When Ruderman received Dinezon’s first letter about the Breslau rabbinical program, he used the opportunity to clarify his viewpoint in relation to Hasidism. From then on, a large and wide-ranging correspondence developed between them.

With time, their letters became friendlier and more intimate. From theoretical topics, they crossed over to the personal. Dinezon initiated this.

He began complaining to Ruderman about his dissatisfaction with himself and his melancholy life. Ruderman answered that he didn’t understand Dinezon’s simple words and wanted to hear clear talk. One day, Ruderman returned to our lodgings from the seminary (we lived together at the time) and said that he had received a letter from Dinezon as long as a megillah in which Dinezon had poured out his heart to him. In this letter, Dinezon shared with Ruderman the whole story of his love from start to finish. To our ears, this did not sound like the usual outpouring of feeling from a man in love but more like a final word, a confession.

With Ruderman’s truly Hasidic optimism, he immediately sent Dinezon a long letter of consolation. It was written half philosophically, half humorously, with great but somewhat too unceremonious disdain for the matter of love in general. He finished the letter with good advice for Dinezon and told him to banish all this foolishness from his head and hurry to Breslau to take up his studies. I added a few lines to the letter. This was, on my side, an answer to the greeting Dinezon sent me in a letter to Ruderman after reading my correspondence from Breslau about the rabbinic seminary in Ha-Magid. [9] I remember that in those few lines, I tried to convince him to abandon Mohilev as soon as possible. We received an answer that he had decided to listen to us and come to Breslau. We waited day in and day out, but he never came.

It was still difficult for Dinezon to leave Badana Hurevitsh’s family and, perhaps even more, the house where the buds of his first and last love had blossomed. At the beginning of the 1880s, when the family moved to Kiev, Dinezon accompanied them, no longer as a tutor but as bookkeeper and treasurer in Hurevitsh’s office.

In Kiev, Dinezon apparently returned to form and, little by little, recovered from his ordeal in Mohilev. He wrote a lot, all in Yiddish, but didn’t publish anything. It was as if he lost all desire to publish at that time.

In 1884, a short time after I published my translation of Pinsker’s Auto-Emancipation, I unexpectedly received a letter from Dinezon saying that since he knew my address, he took the opportunity to inform me that he had been living in Kiev for three years working for the Hurevitshes. He also asked how I was and what I had heard from Ruderman.

I was not able to write anything about Ruderman at that time since we both had left Breslau because we were short of funds, and life had separated us and set us down in different locations. We each had our separate interests and concerns and did not stay in touch. In this letter, Dinezon wrote in passing that he had met the writers in Kiev and “cursed the day he had crossed their paths.”

At the time, I could not understand why the Kiev writers, among them Yehalel, Shatskes, Weissberg, Dolitski, and others, did not appeal to Dinezon to such an extent. It became clearer to me only much later when A. Zederbaum, the editor of Ha-Melits (The Advocate), exposed the entire literary swamp of Kiev for the Yiddish public in a separate supplement to his journal. Through this supplement, it became apparent that the Kiev journalists and writers were bound in nets by all kinds of intrigues, one against the other. The hatred was so great that they would willingly drown each other in a spoonful of water.

It started because an inept hack, the author of a few pieces, was jealous of a writer of true talent. Others who also begrudged him his talent rallied around this petty, envious person, and this set off a whole series of intrigues and slander. For days on end, in league together, they thought up all sorts of lies and libels about the talented writer. They passed these on verbally at first and later undertook to make use of a Galician Hebrew publication with meager content and dubious purity to further their goal. Through this pamphlet, this Kiev gang spread humiliating and preposterous stories with no basis about this popular writer, as well as the editor of Ha-Melits, who had defended his honor.

Through all kinds of intrigues, they also drew in writers who were far from the dirt, both with and without their knowledge.

Without asking or obtaining their permission, they added their signatures to the disgraceful farce. Among those dragged into this circus by this “literary” band without his knowledge was Jacob Dinezon. They signed his name in the pamphlets without asking for his consent. We can easily imagine how such an honest and conscientious soul as Dinezon suffered from these actions.

In a conversation I had with Dinezon about this issue, he said, “A long time after Zederbaum exposed this literary scandal and its participants and I found my name also on the list, I couldn’t show my face. To myself, I felt like I had murdered someone. I sat alone for a few weeks, locked up in my rooms, not even daring to go out in the street. I was worried that someone would run after me and point me out. And it was not that easy for me to take pen in hand again. These people openly desecrated my temple and defiled my altar. I became their blood enemy from then on. I never shook hands with them again nor greeted any of them. I will never forget what they cost me.” He stated those last words with a very nervous agitation.

At the end of the year 1885, Dinezon moved from Kiev to Warsaw, where he resided with his sister, who had a store for artistic feathers. Just before Passover 1886, I came to Warsaw. Discovering that Dinezon was there, I immediately went to visit him. Our first meeting took place on the first day of Passover. I remember that in answer to my question as to whether he had met the writers of Warsaw, he said that since he was still affected by the experience in Kiev, he didn’t trust himself to associate with the Warsaw writers. I explained that Warsaw was not Kiev and proposed visiting a few Warsaw writers of my acquaintance together. On the first day of Passover, we both went to see Hayim Zelig Slonimski, and the next day, we visited Shefer, and so on. Dinezon saw other writers on his own from then on.

IV

One day, while I was sitting in my room, the door opened—and to my complete surprise, in came Pesach Ruderman. I didn’t recognize him at first. In the ten years since I had last seen him, his outward appearance had changed a great deal. Although still middle-aged, his hair was be ginning to gray. On his face lay a certain fatigue and resignation, and with his nervous movements and very poor bearing, he gave the impression of a man who was persecuted by fate and had a lot on his mind.

He told me briefly about his experiences during the previous ten years. His dreams about higher education had gone up in smoke. First in Breslau and then in Berlin, he wrestled with his lot, suffering and enduring a great deal. In the end, poverty defeated him and left him broken. He left for Lodz and became a tutor. In the beginning, he still consoled himself that he would save enough from his teaching to go back abroad to complete his studies. But he was stuck teaching and couldn’t escape. In the meantime, he married and had a wife and three children. His profession never satisfied him, and in time, it ate at his insides until he could no longer stand it and he gave up his hours. Now, he had come to Warsaw, where he hoped to find literary work.

I immediately took him to Dinezon. Dinezon, who until that moment did not know Ruderman personally, always imagined him as he saw him in his letters as a very lively young man, always cheerful and in good spirits, and who carried under his shirt a package of “jokes and jests” to lift up broken hearts and downtrodden spirits. Seeing Ruderman before him in his present state, he at first felt so disappointed that he couldn’t believe his eyes. After I explained the situation to him in a few words, Dinezon asked if he had found a place to live yet.

“I’m staying somewhere near the train station,” Ruderman answered.

“No,” said Dinezon, “that won’t do. It’s too far for you. You need to be in the city. First of all, we need to find you lodgings.”

I couldn’t spend any more time with them and left. The next morning, Ruderman came to me, this time in a brand-new suit and new hat. He told me that the day before, he had walked around with Dinezon for a long time looking for a place to live and had found a room on Muranov. I then understood—and that’s actually how it was—that as far as his new outfit was concerned, it was Dinezon who also took care of that.

That evening, we sat at Dinezon’s and discussed how to secure literary work for Ruderman. At that time, we settled on two possibilities: to obtain employment either in the editorial office of Ha-Tsefirah or from Shefer, who was then publishing his anthology, Keneset Yisrael (The Community of Israel ). The first possibility appeared more likely for the following reasons: first, there was more to do in a newspaper, and therefore the work was steadier, and second, we counted on the fact that Ruderman had studied for three years at the rabbinical seminary in Zhitomir where Slonimski was the inspector and must have known him quite well.

After Ruderman explained that he found it difficult to go looking for work by himself, we decided that Dinezon would go see Slonimski, and I would see Shefer. In one day, the two of us, Dinezon and I, completed our missions. Dinezon returned from Slonimski almost empty-handed, but I worked out something with Shefer.

Slonimski’s response was that he didn’t have a regular editorial position for him; all the positions were filled. However, should he wish to write something and bring it in, he would willingly accept it. Shefer said that right now, he had two or three things to translate from German and Russian for Keneset Yisrael, and later on, he would see.

We could see that we couldn’t hope for much, but in the mean time, Ruderman could get by for now. We talked it over with him and advised him that he should set to work the next day. For now, Dinezon not only “lent” him something for his expenses, he also gave Ruderman a few dozen rubles to send to his wife and children in Lodz.

About ten days passed, and to our dismay, the following happened: Ruderman didn’t write a single line for Ha-Tsefirah. He said that no matter how hard he racked his brain, his ideas wouldn’t jell, and nothing appeared on his paper. He believed, however, that this was only temporary. Not having written anything for so long, he was simply unused to writing. In addition, he hadn’t thought or reflected for some time, and he hadn’t even held a book in his hands for a long time. But it didn’t matter because this would pass quickly. He already had a theme for an article. He had seen Rodkinson’s book, The History of the Pillars of Chabad, for the first time yesterday in the window of a bookshop. He would see about getting a copy and writing a critique. For Shefer, the translations were finished, and he had already submitted them.

When I went to see Shefer the next day, he looked at me very strangely. Drawing out his words as if from tar in his usual complaining manner, he said that it seemed to him that my Ruderman was no longer Ruderman.

“What do you mean?” I wondered.

“Is this Ruderman, the great writer for Ha-Shahar, the great Hebraist, the one-time defender of Hasidism?” Shefer shouted.

“Of course he is,” I said. “What are you asking? This is the same Ruderman, the famous one.”

“If you are so sure,” Shefer said, “come over here. I want to show you something.”

With these words, he pulled out a manuscript from a folder and handed it to me, exclaiming, “Take it and read it out of curiosity!”

Looking at this manuscript, I was almost overcome with shock. Not only was this not the gem-like handwriting that I was well acquainted with from our earlier days, this had the appearance of hieroglyphics, all dots and dashes. But this was not all. After much effort, we recognized the letters and tried to form them into words, but they simply didn’t make any sense. It wasn’t Hebrew, to say the least; it wasn’t even gibberish. I remember standing there for a few minutes, confused, not knowing what to say or even how to begin. Shefer, however, took the initiative and said, “If this is, in truth, the same Ruderman, my opinion is that he is no longer normal. And do you know what else? Yesterday, when he brought me the manuscript, and I chatted with him for a little while, it appeared to me that something was not quite right with him.”

“What are you saying?” I interrupted him. “Dinezon and I have spent time with him daily and haven’t noticed a thing. He is quiet and uneasy simply because he’s discouraged.”

I took Ruderman’s manuscript from Shefer and brought it to Dinezon. It made an even worse impression on Dinezon. It really shook him up, and he sat still for a long time. I related Shefer’s opinion and added, “No small thing, what troubles can do to a person.”

To this, Dinezon replied that we must take Ruderman to a nerve doctor. A few days later, Dinezon went to him and took him out for a stroll. On the way, he took him to a young doctor he knew and with whom he had spoken about this earlier. Through various ruses, the doctor convinced Ruderman that he should be examined.

After the examination, the doctor told Ruderman that he found him in the best of health. In the meantime, the doctor asked Dinezon to come back later. When Dinezon returned that evening, the doctor said, “I found several signs of neurosis and psychic disturbance in your friend. He is in need of a major and careful treatment. First of all, he must not do anything and must get the strictest kind of rest.”

The next day, Dinezon and I went to Shefer to decide what to do about Ruderman. There could be no talk of giving him any literary work or anything else creative at this time. Now we had to see to his cure. But where would we find the necessary means? And we couldn’t abandon his wife and children in Lodz.

Then Shefer offered the advice that we publish something about the situation in the newspapers, a compassionate appeal to the lovers of the Hebrew language and literature. He expressed the hope that this call would have an effect on the Jewish public, that people would begin to send donations to the editorial offices so that it would be possible to send Ruderman to a sanitarium and give his wife and children some support.

Upon Dinezon’s request, Shefer took the responsibility of writing up the appeal. Dinezon remarked that in the call for help, Ruderman’s name should not be mentioned, only that a very well-known Hebrew writer was in need.

In the evening, Dinezon and I visited Ruderman and spent a few hours with him. This time, we both observed him more closely and noticed that he really was not emotionally well. Most of the time, he was deep in thought and very sad. He answered only every tenth word or so. He sat motionless with his eyes frozen in one spot. With much sympathy, Dinezon asked him, “How are you today, Mr. Ruderman? What has become of you? You are a Chabadnik. How did this happen? Do you remember how, once upon a time, you used to console me in your letters from Breslau? Here, I have brought you the honorarium for your translations.” And while he was speaking, Dinezon took two twenty-five ruble notes from his pocket and gave them to him.

Ruderman took the money and said in a melancholy voice that we could barely hear, “So, am I still worth something? I haven’t forgotten everything? It seems to me that there was a Ruderman, but he is no longer here. Here is a shattered vessel, a broken piece of the Ten Commandments.”

With broken hearts, we parted from Ruderman that evening. Neither of us had any inkling that we would never see him again. The next morning at seven, I was still in bed when Dinezon suddenly rapped on my door. He came in white as a sheet and barely managed to say, “Ruderman died suddenly in the middle of the night. The news arrived before dawn from his lodging.”

Dinezon and I went over there immediately. Upon arrival, we found him already laid out on the ground with candles in brass candlesticks burning at his head. The house was empty except for the landlord and his wife, who stood at a loss, wondering what to do next. This man was as alone as a stone and had no family, no relations. Who would take care of his burial?

Dinezon and I took it upon ourselves. Dinezon ran directly to the Jewish Community Council, and I went to see Shefer. Shefer told me right away that concerning Ruderman’s burial, we might have a lot of difficulty. He explained something I had not known before. In Warsaw, there were two Jewish cemeteries, one in the city in Povonzek and the second in the suburb of Praga. In the first cemetery, they bury the Warsaw-born and respected and the well-born Polish Jews. In the second cemetery, they put to rest everyone who wasn’t local and the ordinary people. In particular, the Litvaks were taken to Praga.

“I have no doubt,” Shefer told me, “that those in the Community Council would want to bury this poor and, to them, unknown Litvak in the Praga cemetery. We must not allow that. It would be an insult to the honor of all of us living Hebrew writers.”

I told Shefer that Dinezon had just left for the Community Council.

“Dinezon is not enough,” said Shefer. “Dinezon alone will accomplish nothing. They don’t know him either. I’ll try to go there. Come with me.”

We took the tram to Gzhibov and ran into Dinezon at the gate. He was already leaving with a document. “Where is he to be buried?” Shefer asked Dinezon.

“What do you mean where?” replied Dinezon. “He is going to be buried in the cemetery.”

“In which one?”

“What do you mean, which one?”

It turned out that Dinezon, like me, had no idea about the two cemeteries and who was buried in each one. Checking the document, Shefer saw that, as expected, it referred only to Praga. Dinezon agreed that such a thing should not be allowed and that we had to apply all our efforts to have Ruderman buried in Povonzek.

Shefer left us standing there and went into the Community Council. He consulted with the manager of the funeral desk, told him who the deceased was, and requested he be buried in the city. It didn’t take much more than a minute before Shefer emerged and told us that he had accomplished nothing. In his opinion, the only one who could help us was old Slonimski.

That very minute, Dinezon and I went to see Slonimski. The very characteristic conversation that we had with him has remained in my memory almost word-for-word to this day.

“We have come with not very good news,” Dinezon said. “A former student of yours has died.”

“A student of mine?” the old man asked. “Tell me, who?”

“Pesach Ruderman.”

“Pesach Ruderman?” uttered Slonimski without the least sign of surprise. “He only now arrived, and now he’s dead? Blessed is the True Judge.”

“And the community wants to bury him in Praga,” I blurted out.

“Well, so be it!” Slonimski said as cold as ice.

“It seems to us,” Dinezon responded, “that this is a great dishonor not only for the deceased but also for all of us Jewish writers.”

“Now the young writers are starting to make a fuss!” Slonimski said somewhat angrily. “Apparently you believe that the worms don’t eat in Povonzek? I don’t know what kind of a desecration of honor this is. What does it really matter if he is buried here or buried there? No one is buried twice.”

“It really wouldn’t matter,” I said, “except that from the start, your Community Council has selected one cemetery for people with a pedigree, that is, Polish Jews, and the other cemetery for the lower-class deceased, that includes Litvaks in particular. This becomes a major insult, especially as we are talking not just about a Litvak, but a respected Hebrew writer with a reputation.”

“Then what do you want from me?” asked Slonimski.

“We are requesting that you should be so good as to intercede in front of the community council to have Ruderman laid to rest in Povonzek,” Dinezon replied.

“What? I should go to the Community Council and intercede?” he shouted angrily. “Do you think I have nothing to do? You forget that I have the responsibility of a newspaper. How can you even suggest this to me?”

“Maybe it would be enough if you could write a note to the Community Council. A few words from you would certainly be effective. We beg of you,” said Dinezon.

“I don’t write notes,” said Slonimski in the same angry tone. “I don’t have time to write notes. I haven’t even had a chance to look at the mail today. Look at the huge pile of mail I have,” and he pointed with his finger to a desk where there lay many unopened letters. Dinezon and I remained standing, completely dumbfounded.

Noticing our bafflement, Slonimski said a little softer, “I tell you again by way of good advice. It’s better not to make a fuss over this. Believe me, it makes no difference to the deceased where he is buried. As for the living, spit on that.”

Seeing that nothing would be arranged with this old man, we said goodbye and left. We were already in the foyer when he called after us, “Be sure to let me know when the funeral will take place.”

It turned out, however, that our entire trip to see Slonimski was unnecessary. As Shefer was on his way back from the Community Council, he met the sworn lawyer Yisroel Yasinovski, who at that time was the chairman of Warsaw’s Hibat Zion, and told him the story. Yasinovski, a great devotee of Hebrew literature, took an interest in the matter and quickly went to the Community Council. After a long conversation with the appropriate person, he succeeded in having Ruderman buried in Povonzik.

Ruderman’s funeral was quite small. Not even ten men walked after the casket. There were no more than six or seven Hebrew writers. Slonimski joined us on Gensia Street. Nachum Sokolow joined the small group on Dzika. Neither of them walked further than a few blocks and then disappeared. Of the writers, only five of us remained at the cemetery: Shefer, Eliezer Atlas, the writer and book dealer Abraham Zuckerman, Dinezon, and I.

I am reminded of something trivial. At the cemetery, Eliezer Atlas approached me and asked how Ruderman died. I told him that, according to the doctor, he died of nervous exhaustion. Atlas, who quite often told jokes, sometimes with a purely parochial flavor, responded, “Not for nothing was he known as Ruderman—he lost his rudder.”

“Not always,” I remarked.

Justifying himself, Atlas said, “I mean with respect to his end.”

It was already evening when Dinezon and I returned to the city. We went into a coffee house where we were served tea. Dinezon picked up a newspaper. Sitting next to him, I noticed that tears fell from his eyes one after another as he looked at the paper.

He suddenly turned to me and said, “Ruderman was the only man I ever entrusted with a secret. And now he has taken it with him to the grave.”

I understood right away what he meant. However, Dinezon did not know—and never knew—that for me, this was no secret.

V

From then on, I used to meet with Dinezon quite often, almost every day, especially in the afternoon hours. At that time, he lived with his sister on Nalewki Street, No. 19, in a little alcove, which, in time, became a center for the most respected Jewish authors from Warsaw and elsewhere. Several times in this alcove, I encountered Frishman, Shefer, and Fridberg, and sometimes also Sholem Aleichem and Goldfaden.

They sat on the one bed because there wasn’t enough room for chairs in that tiny little room. However, everyone felt very much at home in Dinezon’s place. Dinezon possessed a great power of attraction. The literary crowd embraced him. Much of this was due to his good and gentle character, his kindhearted nature, and his constant readiness to involve himself in a friend’s situation and help as needed without waiting to be asked.

I could say quite a bit about what Dinezon did to benefit older and younger writers during the mid-1880s. And whatever he did, he did very humbly with unassuming modesty. He treated every writer like a faithful friend or brother. In those days, our writers were not torn apart as they are today in warlike camps between the Hebraists and Yiddishists. The spiritual split between old and young was also not so apparent then. They were all friends and were all drawn to Dinezon.

I remember that almost all of Warsaw’s literary community attended the wedding of the daughter of Dinezon’s sister. The newspaper Ha-Tsefirah almost didn’t appear the following day because the censor at the time, the writer Fridberg, spent all night at the wedding. Fortunately, the “non-Jew” from the editorial office tracked him down, and Fridberg censored Ha-Tsefirah right there at the celebration.

At that time, Dinezon was a great homebody and did not like visiting. He made an exception for only a few houses, or more precisely, for one house. He became very close to the Fridbergs and often went to visit the Fridbergs’ son-in-law, the renowned Yiddish writer Mordecai Spector, who at the time was married to the talented novelist well-known under the pseudonym Isabella (Grinevskaya). Dinezon had only to enter a house once to become devoted to it heart and soul. He then acted like a family member who belonged in the house and shared their sufferings and joys.

Dinezon spent his free time writing. Quite often, he would take out pages he had written a long time ago and rework and polish them before putting them back in the box. He had as yet no thoughts of publishing. But he did have a weakness: if a writer friend came in, he would read aloud from some of his writings. One had to see with what feeling and enthusiasm he read his work! Completely absorbed in his notebook, he did not even glance at the listener as if he had no interest in whether his reading made any impression. He poured such gentleness and sincerity into every phrase that, willingly or unwillingly, he had to touch the listener’s soul.

I used to receive these honors very often. Sometimes, as he was putting the manuscript away in his desk after reading a few chapters from one of his stories, he would say to me with his sweet smile, “I have aired out my children a little bit. Now they will be able to continue to rest. Their day in the sun will surely come.”

I came in one time only to find Dinezon somewhat upset. When I asked him why, he handed me a copy of Ha-Melits and pointed to a letter from Zhitomir signed by a Dr. Shloyme Skomorovski.

This Skomorovski wrote that he had requested permission from the famous historian Professor Graetz to translate his history (The History of the Jews) into Yiddish. Professor Graetz refused, saying that, in his opinion, Yiddish was not a language but a “jargon” that the Russian-Polish Jews should relegate to the archive. Dinezon saw this response from the famous Jewish scholar as a great insult to the Yiddish language and to Yiddish writers.

“We cannot and must not be silent,” Dinezon said. “We must respond to this. Given such an insult, we must protest.”

“Maybe you should be the one to do this. I am sure you know, ‘the one who reads the letter . . .’ (should be the agent to carry out its instructions. Sanhedrin 82).”

Dinezon hesitated. First of all, other than some fiction, he had not written anything for a long time. Second—and this was the main issue for him—he didn’t know where to write. There was the Folks-blat, but he didn’t have confidence in Levi’s newspaper. He was afraid that the editor, a lunatic, would, as was his habit, alter his article and insert precisely the opposite of what he wanted to say. He could write it for one of the Hebrew papers but didn’t know if that made sense.

Not long after, Dinezon told me he couldn’t contain himself and sent an article with a sharp protest to the Folks-blat, pointing out Professor Graetz’s unfounded and false opinions about the meaning and significance of the Yiddish language and Yiddish literature in the life of the Jewish people. Dinezon said, “I had to satisfy my conscience. If Levi comes along and turns my article upside down, it’s not my fault.”

Dinezon’s article opposing Graetz was published in Folks-blat about a week later, just as he had written it, with no changes whatsoever. [10] It was a rare privilege that this time, Levi didn’t twist things and actually didn’t alter anything. In this manner, Dinezon, as early as thirty years ago, was the first to have the nerve to openly fight the antipathy to the Yiddish language expressed in Jewish intellectual circles.

For all his life, Dinezon was a great lover of Yiddish and its literature. He met every new talent with great enthusiasm, even if not a major talent. Every new Yiddish book brought him joy. To this day, I cannot forget his enthusiasm the day he brought me the Yiddish almanac Der yidisher veker (The Jewish Alarm Clock), published in Odessa and edited by Lilienblum for Hibat Tsiyon, even though Dinezon was never a member. The day (Shimen) Frug began writing in Yiddish was a true holiday for Dinezon. With a particular spiritual pleasure, he watched the blossoming of the great Sholem Aleichem’s talent.

Dinezon’s own urge to publish after a fifteen-year silence awakened after the publication of these two significant anthologies: Spector’s Der Hoyz-fraynd (The House Friend) and Sholem Aleichem’s Folks-bibliotek (Folk Library). The vitality that was then developing in Yiddish literature pulled Dinezon back into the stream. He began with a few pieces published in the anthologies mentioned above. Afterward, he began to think about publishing his own literary collection and contributing a long story of his own to each issue. That idea was never put into practice because a short time later, he met Peretz. Peretz later began publishing Di yudishe bibliotek (The Jewish Library) with Dinezon’s financial help and his short novel Hershele.