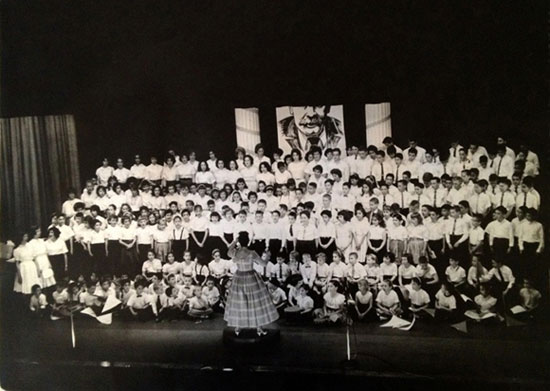

Though I didn’t know it then, I can see now that my childhood experiences singing and acting in Kindershule and Mittleshule concerts at the Wilshire-Ebell Theater in Los Angeles in the 1950s and 60s set the stage for my lifelong interest in 19th century Jewish music, literature, and drama.

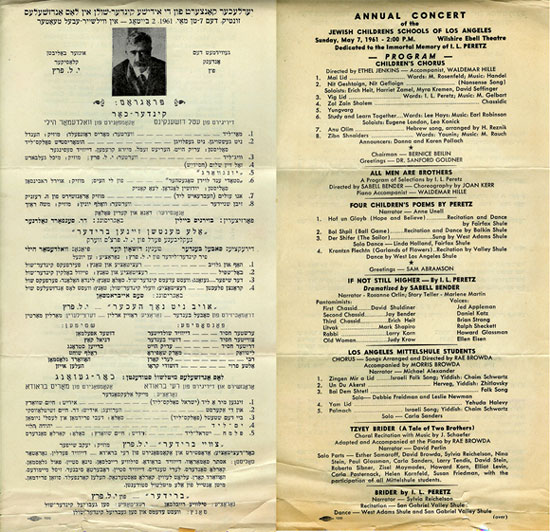

Look carefully and you will see I. L. Peretz’s visage peering out from the back curtain, a reminder of the early influence this once-beloved Yiddish writer had on the young people arrayed before him on the stage. According to the date on the program, it was May 7th, 1961.

As students attending various Kindershules (elementary schools) and Mittleshules (junior and high schools) across Southern California, we all knew I. L. Peretz from the stories we read in class, the little plays and sketches we performed based on his characters, and from our study of the Yiddish culture which he played such a major role in developing and promoting in Russia and Eastern Europe at the turn of the 20th century.

Yet as important as Peretz was in the formation of our young Jewish minds and hearts, he was not half as influential as the elegantly dressed music director at the front of the stage who was conducting our singing.

Ethel Jenkins Weinstein was our San Gabriel Valley Kindershule music teacher, and with her beloved husband, Sid, she not only introduced us to the Yiddish language through songs and music, she also fully engaged us in the Yiddish culture that was reflected in the stories from Peretz’s time.

Most of us in Ethel’s chorus had immigrant bobes and zaydes (grandmothers and grandfathers) who were fluent in Yiddish. Many of our parents, even those like mine who were born in America, grew up with Yiddish still spoken in the home, so they could speak Yiddish even if they couldn’t read or write it. But by the time we, “di kinderlach” (the children), came along and were being taught the language, Yiddish was already losing its battle for secular survival in America.

And for me, personally, learning Yiddish was not an easy task. We only studied it once a week in shule, and the only time most of us heard it in our homes was when our parents used it as a “secret language” to keep us in the dark about things they didn’t want us to know. I also had no ear for languages (high school French would also prove a disaster), and of course after school, I preferred riding bicycles with my friends to practicing a strange foreign language. So, except for a few words, I missed out on the opportunity to learn Yiddish (a regret I carry to this day).

But what I didn’t miss out on were the wonderful Yiddish stories by I. L. Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, and Mendele Mocher Sforim—stories that had fortunately by this time been translated and published in English for young American readers like those of us standing up there on the stage.

And from these stories, and from the Yiddish songs taught to us by Ethel Jenkins Weinstein and our other kindershule and mittleshule teachers (including Sabell Bender who directed our shule concerts), I came away with a deep love for Jewish culture and yiddishkayt (Jewishness). A love that has stayed firmly rooted in my mind and heart—and soul—for all these years.

[Photographs and program courtesy of Ethel Jenkins Weinstein.]