By Jacob Dinezon

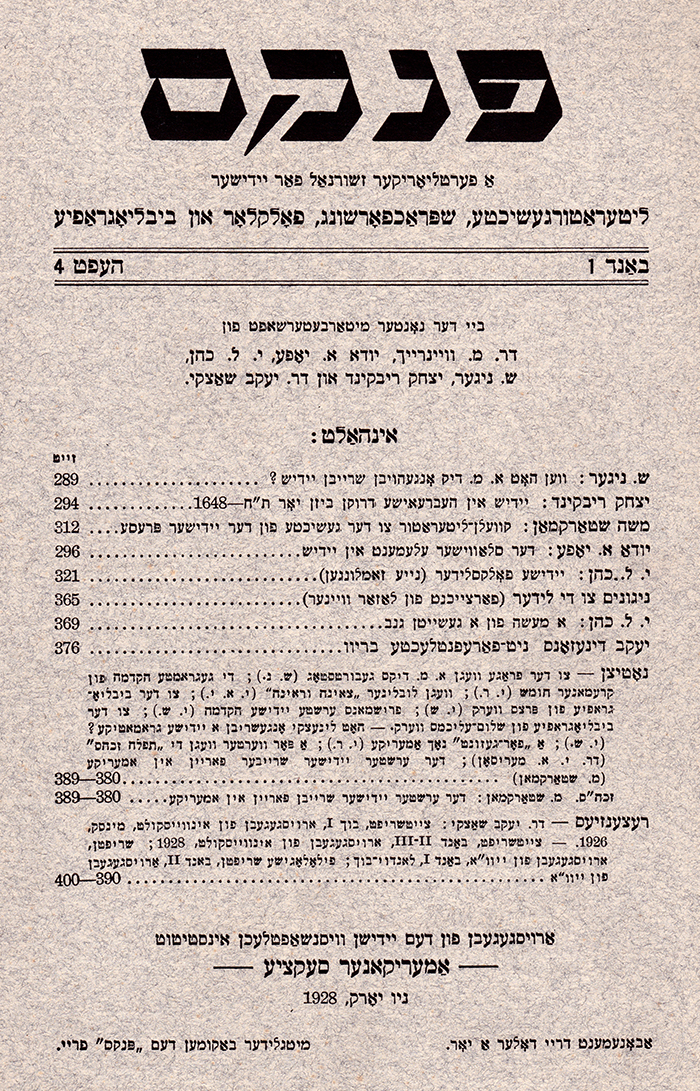

From Pinkes: A Fertlioriker Zshurnal far Yidisher Literaturgeshikhte, Shprakhforshung, Folklor un Bibliografie

(Notebook: A Quarterly Journal Devoted to the Study of Yiddish Literature, Language, Folklore and Bibliography)

Presented by Dr. Yakov Shatzky

New York: The Yiddish Scientific Institute, 1928,

Vol. 1, No. 4, Pages 376–380

Translated from the Yiddish by

Janie Respitz

Thanks to the kindness of the distinguished family that arrived in America a few years ago and were intimate friends of Jacob Dinezon, I have the opportunity to publish some interesting letters he wrote.

The first letter, which is printed here, is dated: Warsaw, Passover, 5669 (1909). Its contents are of great significance for his biography, or more correctly, the psycho-biography of Jacob Dinezon. This letter is so clear that it is superfluous to make further comments. There are a few clarifications which perhaps need to be made due to various reasons, which are, for the time being, premature. As per the request of the proprietress of these letters, I have crossed out the name of the addressee.

The letter has been published with the orthography (spelling) of the original, however, the punctuation has been improved. Other letters will be published in future editions of Der Pinkes.

For the characteristics of Dinezon the letter-writer, see Sh. Niger’s article in the American Shriftn (Writings) (Autumn, 1919, Section VI, pp. 26-28).

Warsaw, the eve of Passover, 5669 (1909)

Most worthy best friend—

It is the eve of Passover today, and what Kosher Jew could find the time on such a day of so much preparation to write letters? I must, however, nevertheless do as my conscience says, otherwise it will plague me at the Seder table if I did not write to the best and worthiest woman and friend. I feel an inexcusable debt toward you. You opened your gentle, beautiful heart to me and showed me all your wounds and painful corners as if to a close, devoted, and tested friend, although I have not yet earned this from you as I know you keep silent even from those closest to you. You wanted me to understand you through and through, to give you my opinion and offer a judgment, and finally, to give you money, which you need to be able to begin everything. And what did I reply to you about all of this? I told you little stories, wrote my own impressions, and, of course, other silly things which could neither cool nor warm you. Am I a good person? Am I an understanding person? I would like to say, with all of my perhaps childish pettiness, I do see others’ open wounds and hear the heart-wrenching cries of their pain and suffering, which they tell me.

Dear intelligent, experienced friend. Please forgive all the difficult, stupid sins I have committed toward you. You once wrote a letter about your true boundless love for Mirele, telling me how, in your small circle of friends, they speak about me as a compassionate man. What can I say? This is true, and I can’t be any different (although I often want to be). Is this how God created me? God gave me more heart than brains, and my heart comes before my intelligence, especially when fighting for existence, and even more so in the struggle between just and unjust, where intelligence enters fate and where energy, strength, and determination are more necessary than everything. My heart arrives first and does not refute its role, and when the heart is regretfully an unhappy hero in war, there is nothing more I can say. Now, my dear, worthy, heartfelt friend, now you understand why my response to your urgent questions was what I felt in my heart and not what my mind should have dictated. I hope at least my loving payment helped you in your difficult struggle between life and death?

Forgive, forgive, great pure soul. I am not worthy of judging you; I can only be amazed and revere you as a holy martyr. This is my conclusive opinion about you, about your acts and wanderings on the path which for you had so many thorns strewn at every step and tore your flesh and wounded your rare, beautiful, humane heart, yet did not affect your pure, uplifted soul.

I have long been thinking that normal humanity, the so-called practical people who love and strive only with their minds, the indiscriminate average people who, willingly or unwillingly, do not scrutinize the oppressed and downtrodden around them, these people know where they are going and they see and achieve their goals. These people sometimes ask what is the shortest path to their goal which they have set for themselves, and it is easy to answer them categorically: right or left. Those who ask, as well as those who reply, belong to the practical world of normal humanity. We, however, my dear devoted friend, you especially and me a bit less, belong unfortunately to the abnormal humans. We are idealistic. We see our ideals before us, often clear and precise, but we forget we are wandering in the desert, and that which we see so clearly is a mirage, a Fata Morgana. We run with a burning thirst to the alleged clear water stream that manifests before us and chases us. We believe that with every step we take with the greatest effort, we are getting closer and closer and barely notice that, at the same time, our ideal is moving further and further away until our last bit of strength is drawn from us and we fall and become buried and concealed in the dry sand of the desert. Very rarely, my beloved friend, little flowers grow out from under our graves . . . sometimes this is at least a bit of comfort in our lifetimes, but who can be sure what will be after our lifetime? Do you think this means it is not advantageous to be idealistic? No, that is not what I am saying. Whether it is worthwhile or not, we cannot be any different than what we are. This is the peculiarity of our souls, the creativity of our hearts. This is how we were created. Our goal is not life but the enrichment of life, the striving, the perpetual wandering, and hurrying to find our ideals. Striving alone is our mission. If possible, every living person should have a mission. I know few happy people who have achieved their ideal and stopped being idealistic as soon as they achieved it.

And because it is like this, because God, the foreseer who manages the world and its creations, had already once arranged everything, we must be happy with our fate and continue to strive for our ideals, and while striving, discover the substance of our lives and not exert any forcefulness upon ourselves. We should live as we please and strive for what we want!

I am caught within my own soul, which you first discovered, my close, beloved friend. In my life’s journey, I have met all types and suffered as you have, my dear friend, almost the same suffering, although on a completely different terrain and domain than you. There were moments when I thought I would, even with pain, tear myself away from my idealistic world and throw myself with heart and soul into the practical world where all happiness and enjoyment and all one needs to shine were present and were almost within my reach. I even tried to stretch out my hand to allow these joys to take me, but I was quickly convinced it would be easier to crawl out of my own skin than hide my soul within, not allowing it to advise me or mixing into my business and poisoning my happiness before I even grabbed it with my own hand . . . People, familiar and unfamiliar, good friends and acquaintances considered me strange: how does someone renounce such happiness! Had those people understood my soul, perhaps they would have understood that a man cannot live without a soul. My soul could not remain with me with that happiness; I rejected that happiness, but I wanted to remain alive. What more can I tell you? It was enough that my idealism led me to a certain level of asceticism, and because of this, I have remained alone and lonely my entire life until today. Perhaps you do not know this, so listen to this inconsolable fact: I have remained unmarried. I do not have and do not know about the soulful affection and gentleness in my lonely half-ascetic life that only a devoted dear woman can provide, and my life would not be as cold and inconsolable as it is now.

My most worthy dear friend, I have never shared these sad facts with anyone before, but since you opened the deep wounds of your pure soul to me, which you hid from others, I am telling you. I want to show you how, for idealists, pure human affection is necessary for the soul, like light and warmth. How much can a lonely soul suffer? How much does it long for a richer ideal? My closest and most intimate friends do not know this about me.

I am, by nature, actually happy and joyful. I mainly complain about bodily aches and pains. I keep the pains of my soul to myself, and as far as I know, nobody suspects that there is so much longing and starvation within.

Therefore, I understand your soul; therefore, I understand you so deeply, and, therefore, I can feel and sympathize with your pain and suffering. I can also sympathize with your gentle beloved Mirele, and my heart cries within why you both cannot be happy as I would like to see you in my life. I only know how I can help you with your happiness, believe me, with my whole life, with all that I possess, with all my wished-for joy, I am ready, in every pure, sacred sense, to do whatever I can for you and for dear Mirele. Why? How can I explain without being misunderstood? I explain this to myself as I feel your hearts in my own heart. I recognize my own soul in your souls. I feel comforted that my soul longs for and is attracted to such pure souls as I recognize in you, most worthy friend, and in kind-hearted beloved Mirele. This comforts me because it clearly shows me that my own soul occupies the divine purity, the untarnished elements of life; I do not love that which shines and sparkles but rather that which is honest and distinguished in the divine spirit within us.

I request nothing in the world from Mirele and from you except for your pure, rich, heartfelt, intimate friendship. Let our pained hearts open up for the three of us, and we should not be ashamed of our faults or take too much pride in our virtues. Let us have pure, assured convictions that our hearts do not only belong to ourselves but to all three of us. Each of us carries only one-third of ourselves in our bosom. How I wish for such friendship, dear woman! How I have searched for this in my small, idealistic world. My life has been so sad and uncheerful because until now I have not found this!

I believe, and I am convinced that I have found this in you, my dears. This boundless trust you both bestowed on me from our first written communication reassures my convictions, and I feel happy and joyful. I am now aware that somewhere, there is a heart that is a part of my heart, and it feels so good that I understand the part that is within me, pure and untarnished, with each part protected, far from egotistical findings and unworthiness. It makes no difference to me if the place is called Shpikov, Warsaw, Jerusalem, or Babel. Closeness and distance do not exist for the soul, just as boundaries and fences also do not exist.

The soul will enter wherever it wishes. Do you feel, my darling friends, that such a friendship is a blessing? You can be sure you are lacking nothing from your own hearts, which live in me and are dearer to me than my own life and not any less precious than my own heart, which I see in you. With such a pure and strong conviction, I hope you will be able to turn to me, without ceremony, as it is called, as you would to yourselves, to speak from your hearts, cry when necessary, and allow your souls to breathe freely when your body is experiencing difficulties, and the pressure of fate is suffocating. Do this, dear friends. This will make your difficult lives easier. This is the only way I can help you. I cannot help you in any other way, but I can try to talk to you as much as possible.

And you, my listening, deeply thoughtful friend, I can only advise one thing to you if you promise to listen: throw away your doubts. Do not immerse yourself too deeply in your gentle soul. Believe in yourself, in the pure feelings of justice and sincerity! Whatever you do is correct! . . . Whatever fairness dictates to you cannot be incorrect. Constant doubt is like a terrible worm that gnaws at your heart and poisons your soul. In truth, a person is subject to making mistakes; however, the absolute truth is that our human spirit has not yet been attained. What today shines for us as the truth can prove to be untrue tomorrow. But we must only consider today as tomorrow can show us something different. Only when tomorrow becomes today can we live with the truth and allow others to do the same.

Be well, my gentle friend,

Your Dinezon.